Scientist of the Day - Justus von Liebig

Justus von Liebig, a German chemist, died Apr. 18, 1873, at the age of 69. Liebig was a pioneer in organic chemistry, agricultural chemistry, and chemical education, perhaps the greatest German chemist of the 19th century, certainly the most influential one. His father made and sold paints and pigments, so Liebig was exposed to chemistry at an early age, and it seized his interest from the start. After apprenticing briefly as an apothecary, he attended the University of Erlangen, then went to Paris, where he worked with Joseph Gay-Lussac and was befriended by Alexander von Humboldt. He returned to Erlangen to pick up his degree, and then was appointed (on Humboldt’s recommendation) to the faculty at the University of Giessen, where he would teach until 1852.

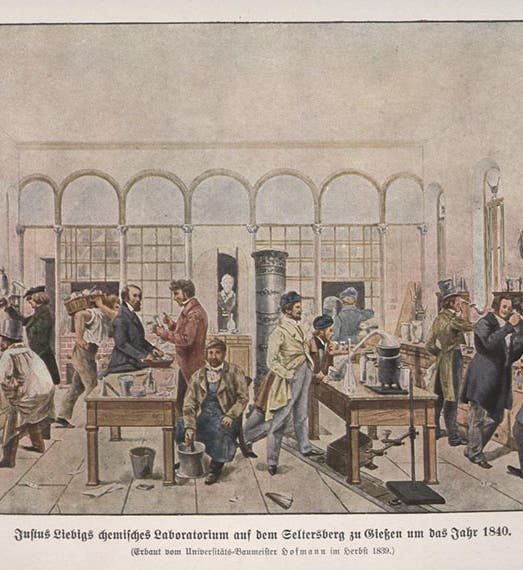

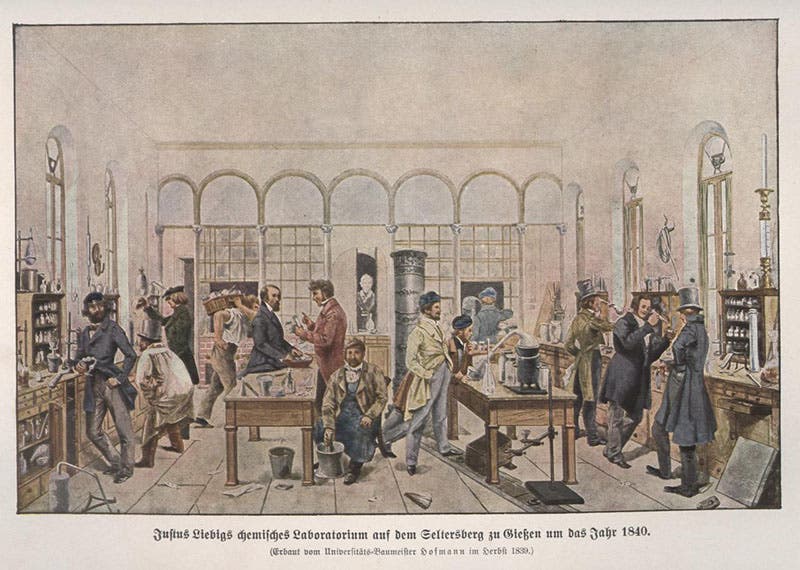

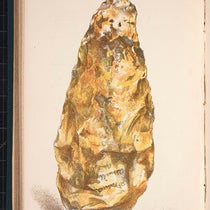

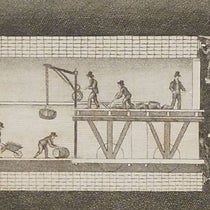

Liebig was initially given no laboratory allowance, and the university refused to allow him to set up a lab to train apothecaries, so he did so as a private venture, and his teaching laboratory was a great success. Indeed, there were no teaching chemical laboratories in existence anywhere until Liebig set his up, where he could provide hands-on laboratory instruction to 9 or 10 students at a time. Eventually, university officials saw the advantage of a teaching laboratory and provided him with funding and a university rubric. His teaching laboratory became a feature of the university, perhaps its most notable one, and was featured in a lithograph of 1840. We show a later chromolithograph version of the original (first image).

Liebig spent much of his career – especially the early period up to 1840 – analyzing various organic and inorganic substances, trying to establish the chemical makeup of each. At a time when even the atomic weight of simple elements such as carbon and oxygen was up for debate, this was not an easy task, and Liebig’s conclusions were often challenged by other chemists such as Jakob Berzelius. But the techniques Leibig and his rivals developed gave chemistry a solid professional basis. We have several dozen books by Liebig in our collections, although most are later editions, since his works went through many printings and translations.

One of Liebig’s most influential books was Die organische Chemie in ihrer Anwendung auf Agricultur und Physiologie (Organic Chemistry in its Application to Agriculture and Physiology) (1840), which we have in a later 1842 printing (third image). Here Liebig tried to apply chemistry to the problems of plant nutrition, even though he had little experience in agriculture. He was able to determine that plants derived their carbon, not from "humus," but from the carbon dioxide in the air, and hydrogen was broken down from water. The big problem was nitrogen, which is abundant in the atmosphere, but chemically inaccessible to plants. Instead, Liebig argued that plants derive nitrogen from ammonia dissolved in rainwater. He is called the father of the fertilizer industry, although it is not clear that any of the fertilizers he recommended had any value. Techniques for nitrogen-fixation would not be developed until the next century.

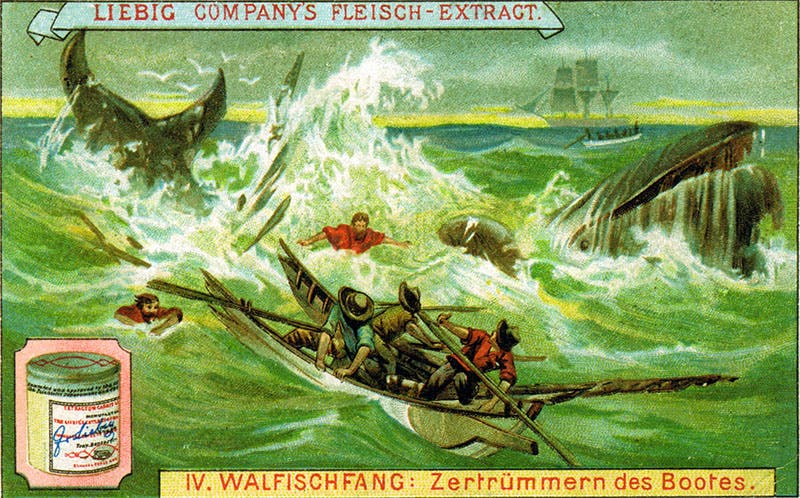

Liebig also write a book on animal chemistry, and another on the chemistry of cooking (1847). In the latter, he argued for the importance of meat juices in human nutrition and advocated the production and sale of liquid meat extract. Companies were established in the 1860s to sell meat extract, some with Liebig’s blessing and participation, some (especially in England) without. Meat extract was all the rage by the end of the century, and eventually gave rise to its most long-lasting byproduct, the bouillon cube. These were marketed by Oxo, a company derived from Liebig's Extract of Meat company in England. It turned out, unfortunately, that Liebig's Meat Extract had almost no nutritional value. But the promotional cards printed as ads for Liebig’s Meat Extract are still a popular side-item for collectors of chocolate, cigarette, and tea cards (fifth image).

Liebig taught at Munich from 1852 until his death. There is a statue of him there, in Maximilian’s Square (fourth image). If you would like to see this statue on a Liebig Extract of Meat card, try this link. Liebig’s grave, with another monument, is in the Alter Südfriedhof in Munich (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.