Scientist of the Day - Pierre Belon

When I wrote a post on Conrad Gessner two days ago, I was surprised when I tried to add a link to Gesner's worthy contemporary, Pierre Belon, and found that we have never published a post on Belon. I soon realized why: Belon has no known birthday or death date, so he never showed up in any of my date searches. I determined to remedy this lacuna as soon as possible, and the cure begins today, and will continue tomorrow. By Friday, Renaissance natural history will be back on a firmer footing.

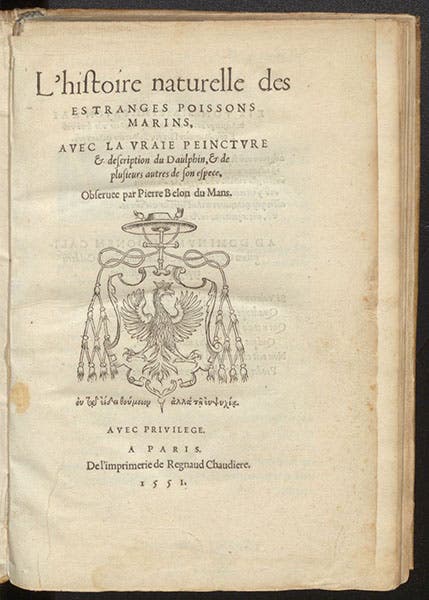

Belon was born in 1517 in a village in northwestern France, and grew up in Le Mans. He showed great ability and attracted patrons early on, who sent him to school, where he studied to be an apothecary, and who supported Belon on a series of travels. From 1546 to 1549, he made his way through Greece, the middle East, and Egypt, where he was mostly attracted by the natural history of the areas he visited – the birds, animals, and fish. Somewhere along the line, he acquired a classical education, for he knew Aristotle's History of Animals inside and out. But what distinguished Belon from Gessner and every other naturalist of the 1550s is that his primary input came from personal observation. Citations to classical authorities are few and far between in his writings, which began to appear in print in 1551. Today we are going to look at that first book, a slim volume called L’histoire naturelle des estranges poissons marins (A natural history of unusual marine fish), published in Paris in 1551.

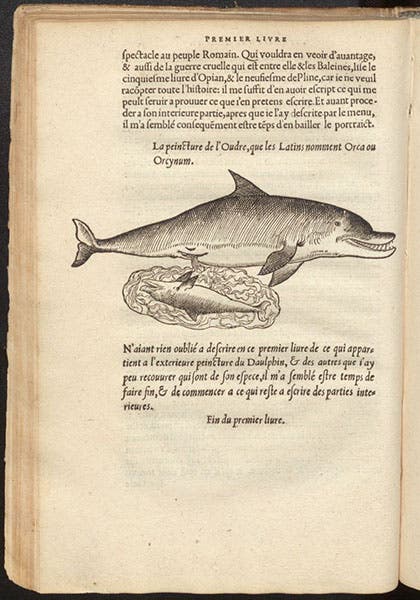

The book starts out as an essay on the dolphin, highlighted by Belon’s personal discovery that it is not a fish at all, but carries its young in a placental sac and gives birth to its young alive. The same is true of other marine animals – we are tempted to call them marine mammals, but that word does not yet exist – such as the orca, which we see pictured in a woodcut, along with its newborn progeny (third image).

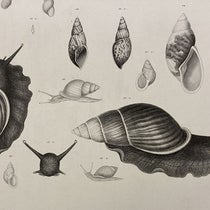

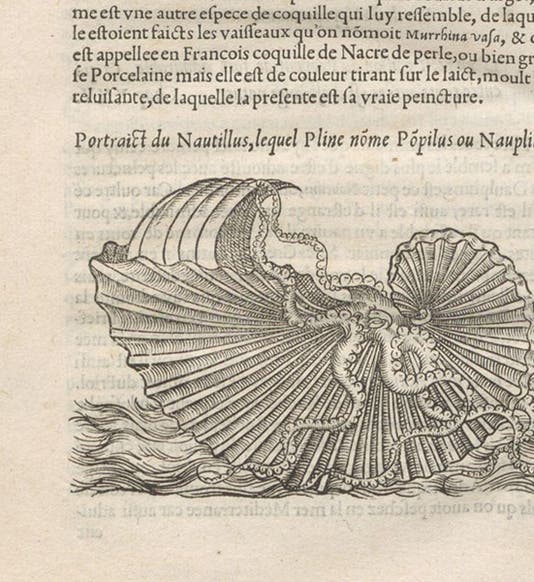

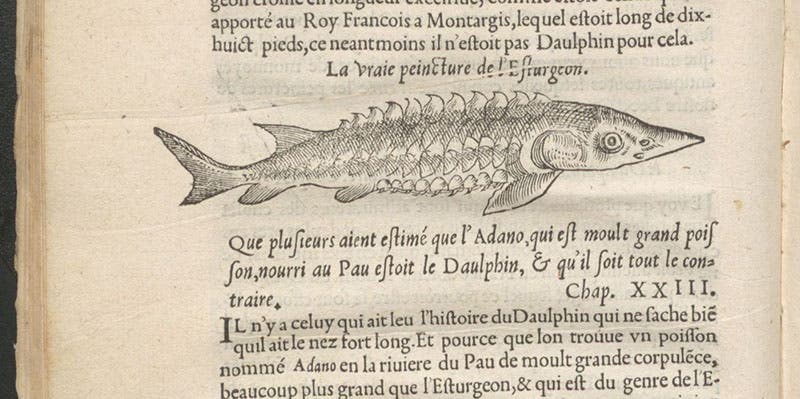

Belon then moved on to discuss other unusual marine creatures, such as the sturgeon. In nearly every case, he added a woodcut of the animal or fish under discussion, and often stressed, as he does here, that it is a “true picture” (fourth image). All of the images in the book are new, which itself is a novel feature in books of natural history. The sprightly woodcut of a paper nautilus under sail (first image) was one of the few fanciful images one can find in the book, although the details of the nautilus itself were undoubtedly derived from first-hand observation.

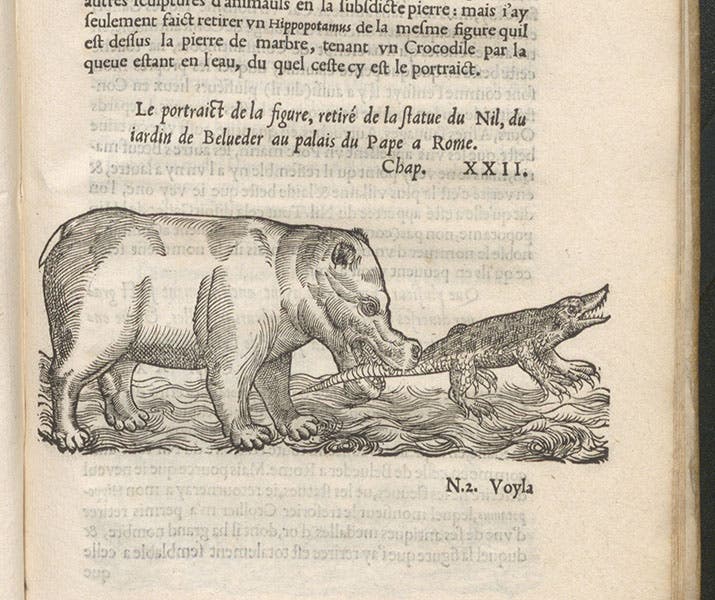

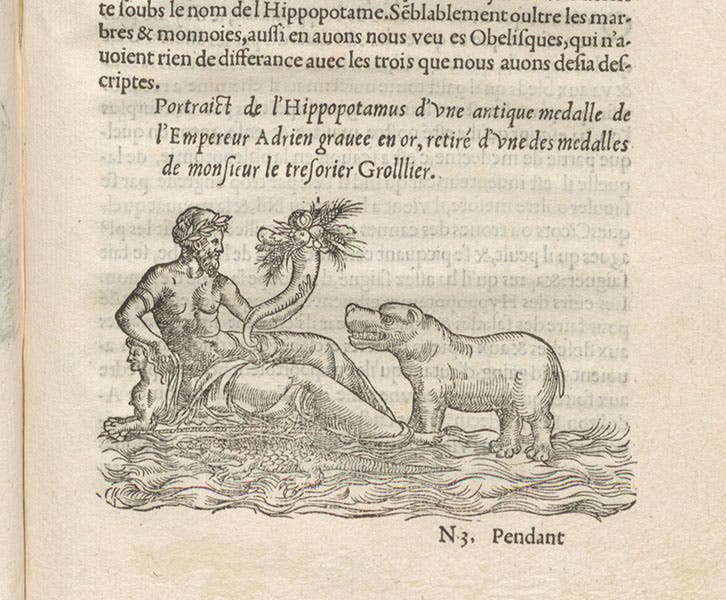

Several of the images in Belon’s book have been reproduced in modern secondary sources to show the credulity of Renaissance naturalists, such as the two depicting a hippopotamus (fifth and sixth images), as if naturalists of the time believed that hippos snacked on unusually stiff crocodiles. But Belon’s caption clearly states that the image came from a statue of the river god Nile that Belon saw in the Belvedere Gardens in Rome. The other woodcut, which depicts the river god and a hippo, was taken from the back of a medal minted for the emperor Hadrian, as the caption again informs us.

When Belon wrote his first book, the first volume of Gessner’s Historia animalium (1551-58) had not yet been published, so Belon was laying out his own path. Where Gessner would emphasize classical erudition and give the widest possible scope to natural history, Belon tended to focus on the things he personally observed, with no reference to fables, emblems, and proverbs, as one finds in Gessner’s volumes. Both shared a predilection for images drawn from life, although Gessner often had to rely on images supplied by others, or ones taken from his reading. The one thing that Belon would take from Gessner is the realization that his own writings should be more encyclopedic, and not as selective as his 1551 book. We will see this in our next installment tomorrow, when we look at Belon’s second book, the wonderful De aquatilibus (On water creatures, 1553), which, with its oblong format and delightful woodcuts, is one of my favorite books in our entire collection.

There is only one contemporary portrait of Belon, a woodcut in his last book, a history of birds (1555), which we will not discuss until our third and last post on Belon, sometime in the future. Perhaps I will include a later portrait, derived from that original, in our post tomorrow. Or perhaps I will just wait.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)