Scientist of the Day - Pope Urban VIII

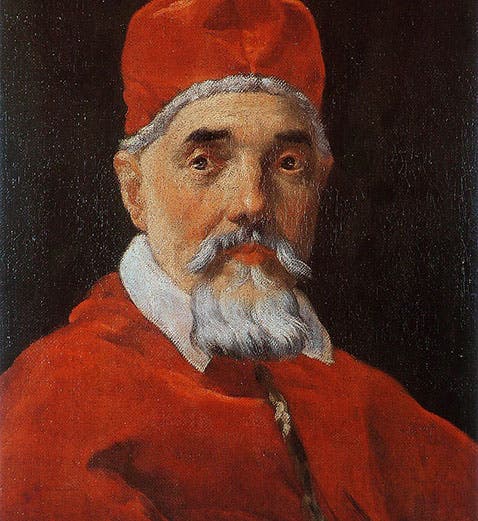

Maffeo Barberini, an Italian cleric, was baptized Apr. 5, 1568. He is better known as Pope Urban VIII, a post he was elected to on Aug. 6, 1623, and which he held for the next 21 years, until his death on July 29, 1644. He commissioned many great works of art, quite a few, admittedly, depicting himself, and was patron to the great sculptor and painter Gianlorenzo Bernini. But he is best known for nearly bankrupting the Church with his fiscal irresponsibility, and for his run-in with Galileo Galilei. It is the latter that will occupy us here.

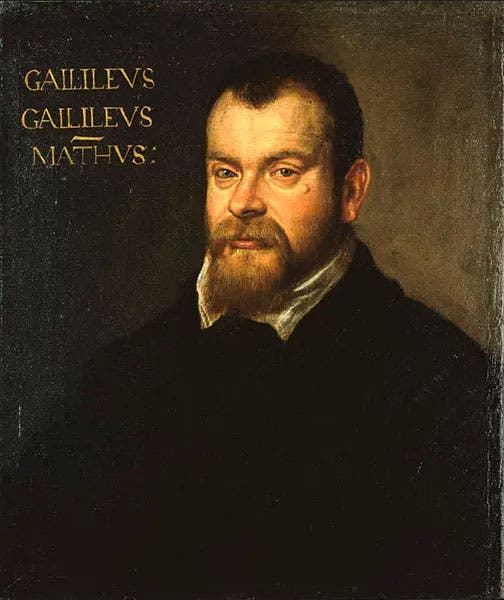

Barberini met Galileo at the Medici court in the early 1610s, long before he became Pope, and the two men seem to have hit it off reasonably well. The portrait (second image) shows Galileo as he would have looked when he first met Maffeo. Barberini knew of Galileo's Copernican leanings and did not object, except to point out, on occasion, that humans are hardly able to determine, by reason and experience, what God could and could not do in constructing the cosmos. His powers are so far beyond ours that we are helpless to figure things out without scriptural guidance.

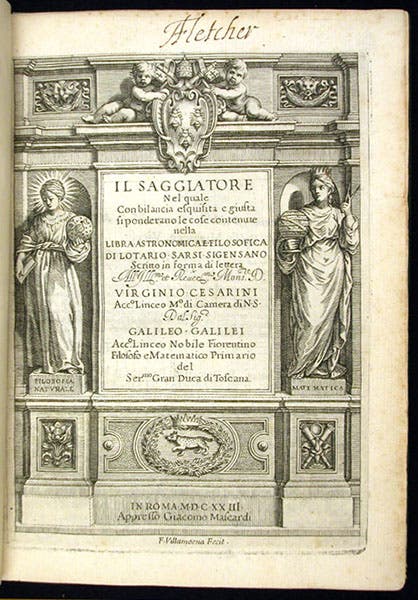

Barberini played no role in the “Galileo affair” of 1616, when Copernicanism was ruled heretical and Galileo was told he could not hold or defend such beliefs.. Galileo, as a result, shelved his intended book on the structure of the world. When Barberini was elected Pope in 1623, Galileo was quit excited, believing that he now had a friend and supporter in the Vatican. When Barberini was elected, Galileo was in the process of publishing his Il saggiatore (The Assayer, 1623), a book ostensibly on the comet controversy of 1619, but actually a treatise on scientific method. He was so encouraged by Urban VIII's accession to the papal throne that he put the new papal arms, which incorporated the Barberini heraldic motif of three bees with the papal keys and tiara. right on the engraved title page of his new book (third image, with a detail of the papal arms below). And Galileo thought that this might be a good time to resume his treatise on the two chief world systems.

Ten years later, Galileo no doubt had second thoughts about his enthusiasm, when he was ordered by Urban VIII to stand trial for defending the heretical doctrine that the Sun was at the center of the world. Galileo had published his Dialogo (Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems) in Florence in 1632, and he had secured all the necessary imprimaturs from the church censors. The book was widely acclaimed in Florentine circles. But within a short time, it became evident that Urban VIII was outraged by the book, and felt that Galileo had betrayed him. The most probable explanation for this turnaround by Urban is the fact that Galileo inserted the Pope’s argument – that God has powers to arrange the world that were far beyond our powers to understand – into the mouth of Simplicio, the simple-minded Aristotelian interlocutor used by Galileo as a foil in his discussion of cosmology, at the very end of the Dialogo. Galileo’s enemies at the papal court – and he had many – apparently convinced the Pope that he had been made to look like a fool, and Urban was not at all pleased. Many historians think that, were it not for Urban’s ire, the case would never have gone to trial, or it it had, there would have been no condemnation.

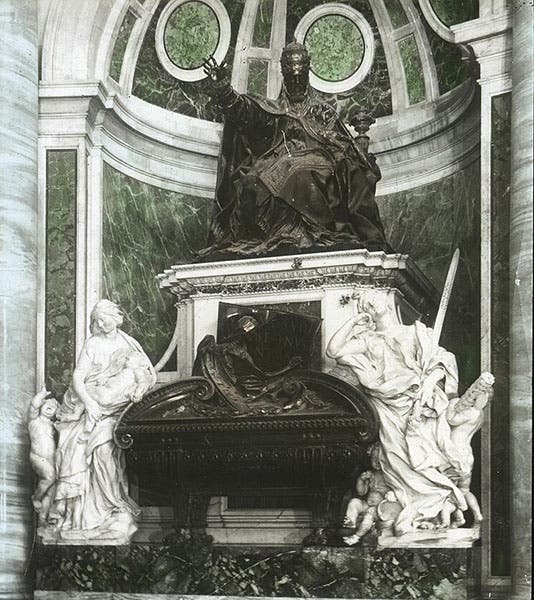

Urban apparently could hold a grudge. When ten years later, after Galileo’s death in 1642, his friends and disciples wanted to construct a chapel in his honor in the Church of Santa Croce in Florence, the Pope forbade it. Galileo would not get his shrine until 1737. Urban himself got a grave monument much quicker; after his death in 1644, Bernini executed yet another sculpture for a tomb in Saint Peter’s. It is a grandiose baroque affair, and should you ever visit in person, see how many Barberini “bees” you can see flitting about the memorial (sixth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.