Scientist of the Day - George Pollard, Jr., and Owen Chase

George Pollard, Jr., was captain of the whaling ship Essex, and Owen Chase was his first mate. Neither was really a scientist, but both were present at one of the most impressive impact studies of modern times. On Nov. 20, 1820, the Essex was rammed amidships by a huge sperm whale, estimated to be 85 feet long, just about the length of the ship. Pollard and Chase were out in separate whaleboats at the time, hard at the chase of a pod of whales, with only a skeleton crew on board the Essex. After the first impact, the whale retreated some distance, put its flukes into overdrive, and struck again, this time head-on at the bow. The ship was broken apart. When Pollard and Chase got back, they barely had time to retrieve stores and water before the ship sank. After three months at sea in the whaleboats, and more than one episode of cannibalism, eight of the crew were rescued, including Pollard, Chase, and the cabin boy, Tom Nickerson.

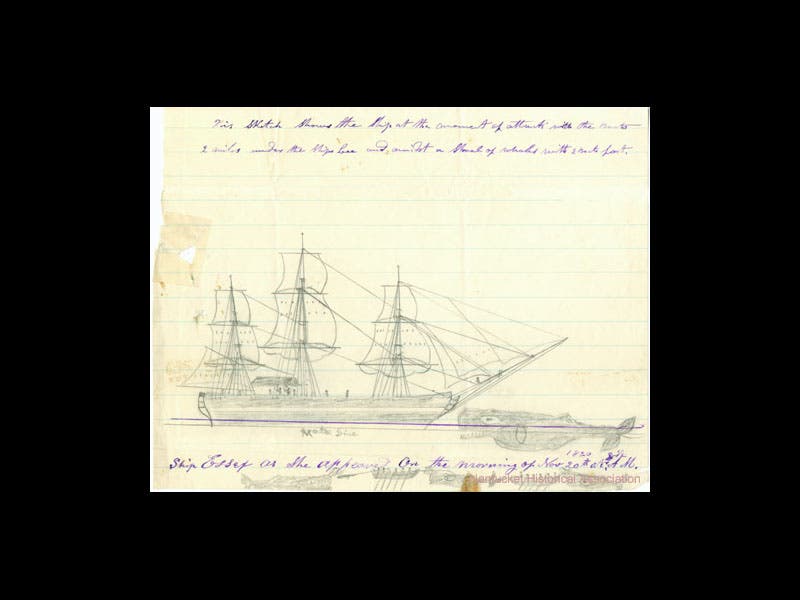

Having survived this unprecedented encounter between whale and whalers, Chase published an account of the ramming, Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex (1821; second image). Herman Melville was only one year old when the Essex went down, but in the 1840s, he read Chase's book, and he also met Pollard back in Nantucket and was greatly impressed by the captain. There were other narratives that also influenced Melville, but there is little doubt that the ramming of the Essex was a major inspiration for Moby-Dick (1851).

Nickerson, the cabin boy, lived to be a salty old tar, and in his later years, he wrote an account of the sinking. The narrative was lost for over 80 years and was only rediscovered in 1960. It took 20 years to prove its authenticity, and once that was established, noted maritime historian Nathaniel Philbrick set out to write a book about the Essex disaster, using the accounts of both Chase and Nickerson as source material. In the Heart of the Sea (2000) won the National Book Award for nonfiction. Philbrick's book was then made into a movie with the same title in 2015, but the film was a bust, even though it had Chris Hemsworth, who is Thor in his other life, playing Owen Chase, and Brendon Gleeson, everyone's favorite crusty Irish actor, in the role of the reminiscing Nickerson.

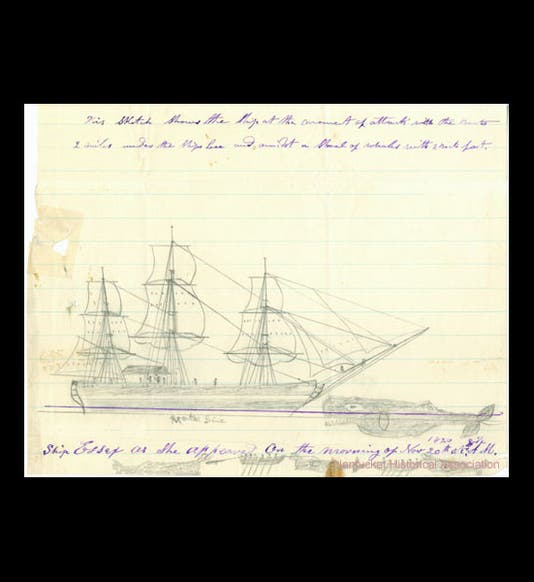

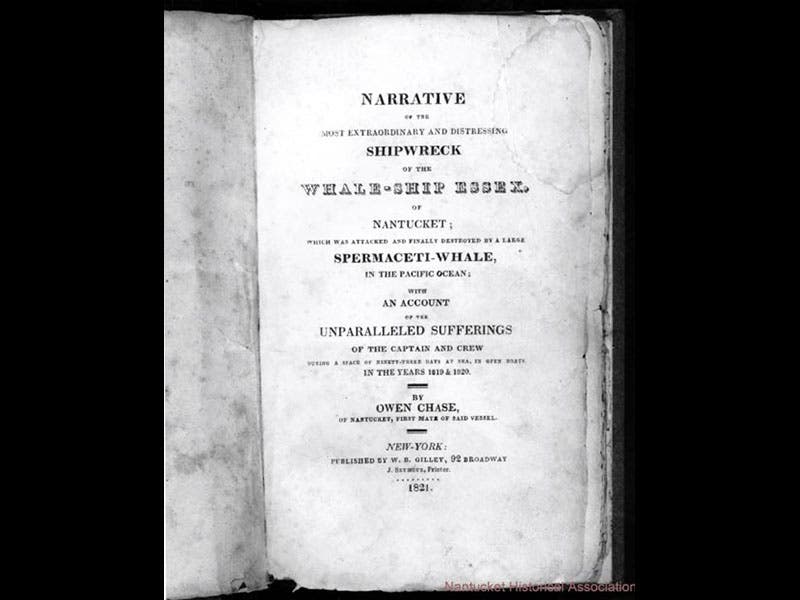

We have no images of the Essex, except for a sketch by Nickerson of the second ramming (first image). But we do have several contemporary oils of a sister whaler, Spermo, painted in 1822 and 1823 (third image). Using these as a guide, several craftsmen have produced models of the Essex for display at whaling museums, such as this one at the Nantucket Whaling Museum (fourth image). The Peabody Essex Museum also has a painting that gives us a graphic idea of the dangers involved (for both species) when humans confronted sperm whales in the open sea (fifth image).

And just to reestablish the science connection, a recent study, published in 2016 in PeerJ, revealed that the sperm whale head is well-adapted for ramming, and that even though such encounters are rarely seen on the ocean surface, perhaps they are a more frequent occurrence at depth.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.