Scientist of the Day - Guillaume-Joseph Le Gentil

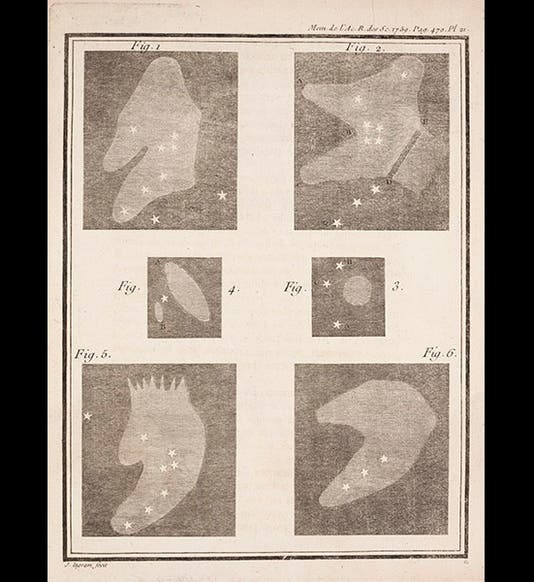

Guillaume-Joseph Le Gentil, a French astronomer, was born Sep. 12, 1725. In his early career, Le Gentil (or Legentil) was interested in nebulae, and he discovered two open star clusters that would later be named M36 and M38. In 1749, he observed that the Great Nebula in Andromeda has a dwarf companion. The large nebula would eventually be labeled M31, and Le Gentil's nearby dwarf would be called M32. In 1759, Le Gentil published a plate in the Memoires of the French Royal Academy of Sciences that showed four views of the Great Nebula in Orion (first image). Two of the drawings (Figs 2 and 6) were his own; the others were by Christiaan Huygens and Jean Picard. At left-center (Fig. 4) there is a drawing--the first published drawing—of Andromeda’s M31 with its tiny partner. M32 is labeled "B" in the engraving.

Le Gentil's nebula studies came to an end in 1760, when he was sent by the French Academy of Sciences to Pondicherry, India, to observe the transit of Venus of 1761. The hope was that, if enough astronomers measured the time and position of the transit from different places on earth, then the distance to the sun could be triangulated. Pondicherry, however, had just been captured by the British, so Le Gentil had to observe the transit from a rolling ship, and precise observation was impossible. Now, transits of Venus occur every century or so, but then they come in pairs, eight years apart. Thus, there would be another transit in 1769, and so Le Gentil thought, what the heck, he might as well stay around until the next one. Therefore he travelled about the Indian Ocean, and journeyed to Sumatra and the Philippines, until 1769, when he returned to Pondicherry, now back in French hands. At the moment of the transit, the sky clouded over, and again he was unable to make any useful observations.

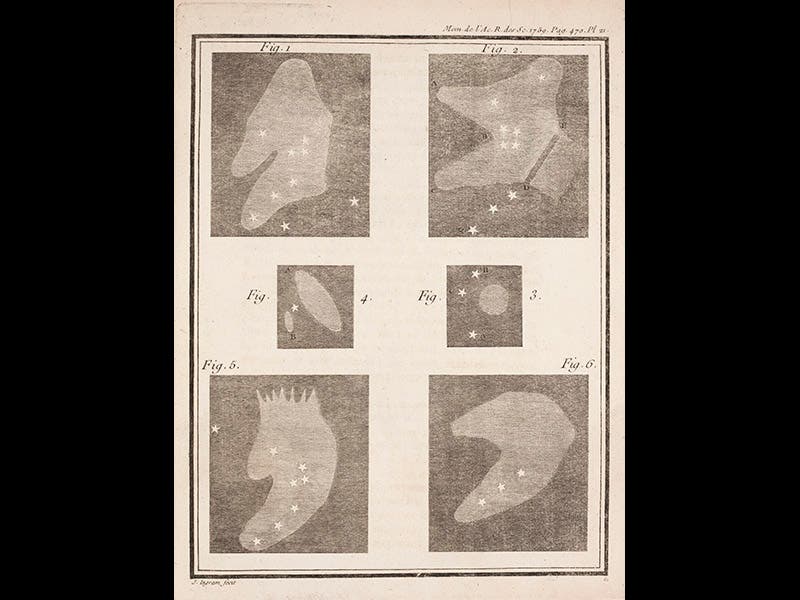

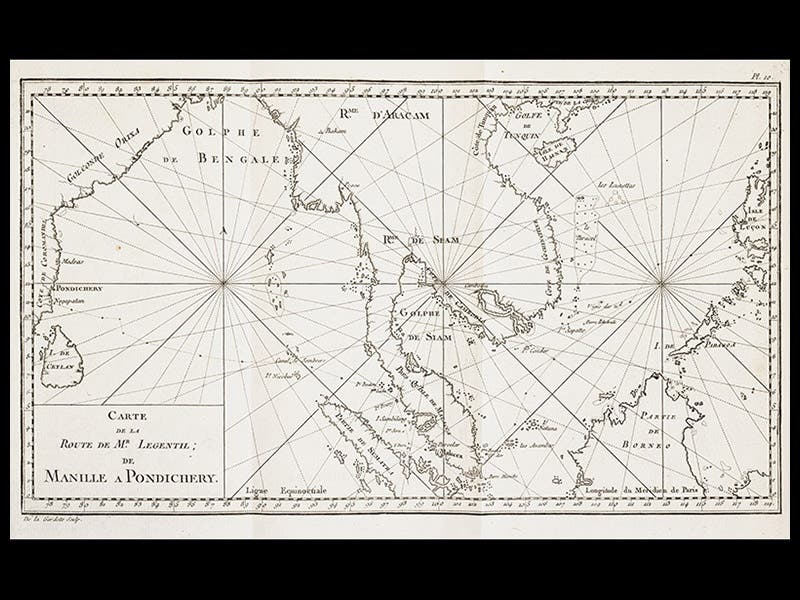

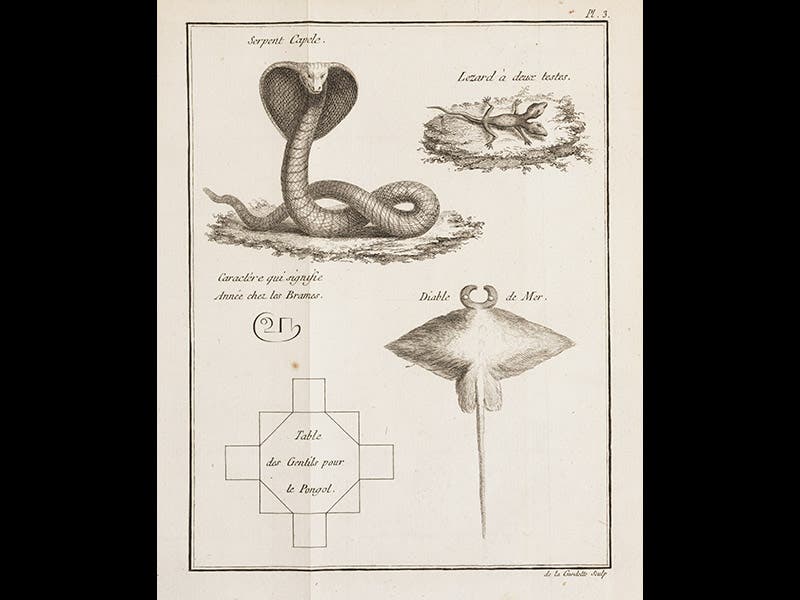

So Le Gentil returned home, with nothing to show for his eight years in India, and he found that his family had declared him dead and had divided up his estate, and he had been removed from his position at the French Academy of Sciences. Eventually he retrieved his finances and his job, and he later wrote a book about his eight-year saga in quest of the transit, which we have in our History of Science Collection. The Voyage dans le Mers de Inde (1779; third image) not only illustrates the French observatory at Pondicherry (second image) and maps Le Gentil’s journey from the Philippines to India (fourth image), but it depicts many other objects that attracted Le Gentil’s attention, such as the ominous hooded cobra (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.