Scientist of the Day - Jeremiah Dixon

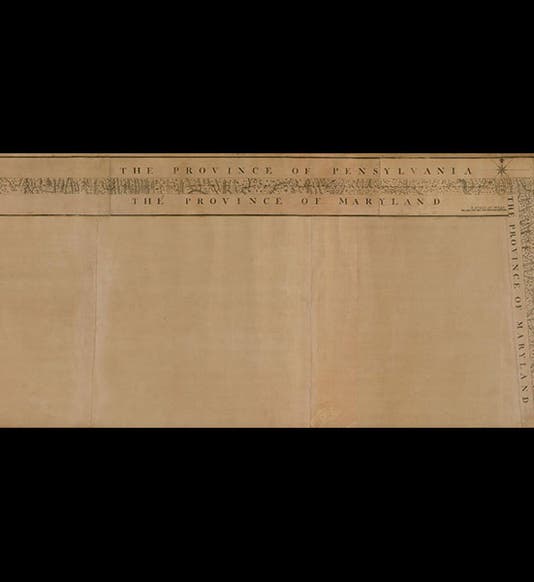

Jeremiah Dixon, an English surveyor, was born July 27, 1733. In 1761, Dixon teamed up with another Englishman, Charles Mason, to observe the transit of Venus in South Africa, and the two worked well together. So when the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland were looking for a team to survey the disputed boundary between them, they hired Mason and Dixon for the task. They began work in 1763, on the "vertical" part of the line that divides Maryland from Delaware (then part of Pennsylvania), and after laying out the north-south portion, they returned to Philadelphia and began the western segment. So meticulous were they that it took four full years to lay out the complete Mason-Dixon line, the east-west portion of which extends for some 233 miles. It was said that as they worked their way westward, the local families that they passed learned for the first time whether they lived in Pennsylvania or Maryland. The line was not particularly notable to anyone but locals for the next 50 years, but in the early 19th century, it came to prominence as the effective dividing line between North and South.

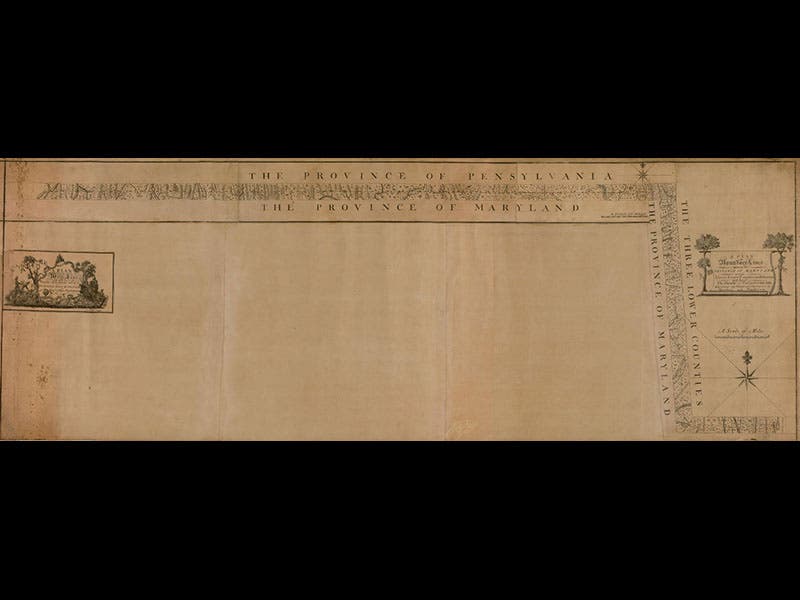

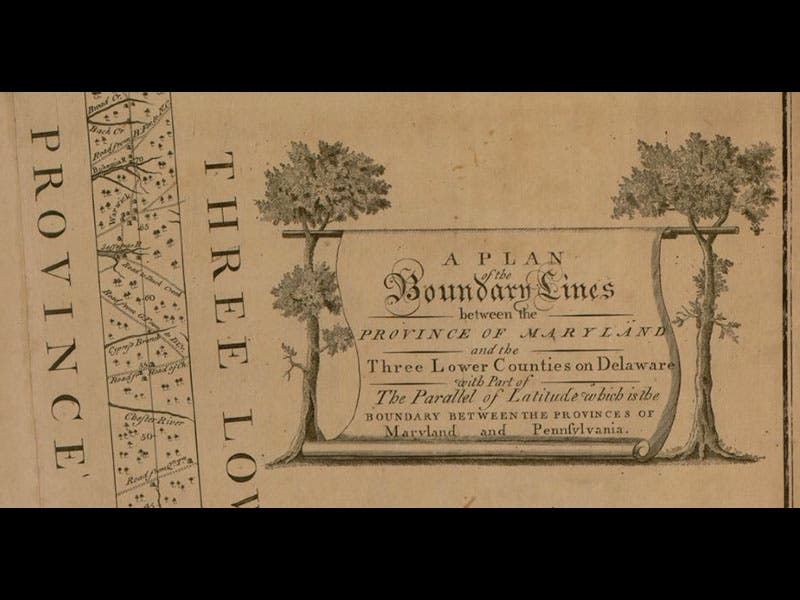

The Mason-Dixon line was published as a map in 1768--a very strange map, as you can see (first and second image above; the second image is a detail of the far right of the map). We do not have the map in our collections. As they laid out the boundary line, Mason and Dixon placed marker rocks every mile. The mile markers had a “P” carved on the Pennsylvania/Delaware side and an “M” on the Maryland side, and a great number of them survive (third image). Every five miles, the duo placed a more elaborate stone--taller, with the family crests of the Penns and the Calverts carved on them. The stones with crests, the ones that have survived, are often protected by small wrought-iron enclosures. The one shown above, placed at the point in central Delaware where the line makes its right angle turn to the east, has the advantage that the two crests are only 90 degrees apart and can be seen at the same time (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)