Scientist of the Day - Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus, a Spanish physician and would-be religious reformer, was born (it is said) on Sep. 29, 1511, in Villenueva de Sigena in Aragon. While in the entourage of the Emperor Charles V, Servetus published an anti-Trinitarian pamphlet (1531), and religious denunciation was so strong--from both Protestants and Catholics--that he moved to France and assumed the name Michel de Villeneuve. He studied medicine at the University of Paris in 1536, and during his subsequent medical practice, he discovered the pulmonary circulation--that blood goes from the heart to the lungs and back to the heart. This was actually a very big deal—the first assault on the theory of blood flow of the ancient Greek physician Galen, some 90 years before William Harvey would resume the attack. At the same time, Servetus entered into correspondence with John Calvin in Geneva, a correspondence that grew quite heated over the years, as Servetus denounced not only the idea of the Trinity, but Calvin's doctrine of predestination.

In 1553, while working in Vienne in southeastern France, Servetus published (anonymously) another religious tract, The Restitution of Christianity, in which he continued his assault on Trinitarianism. Interestingly, the book contains a section in which Servetus first revealed his discovery of the pulmonary circulation. Since Calvin had earlier published a book called The Institution (or Institutes) of Christianity, Servetus's book was clearly a direct attack on Calvinism. A friend of Calvin's identified Servetus as the author and denounced him to the authorities in Vienne. Servetus was arrested and tried for heresy by the Catholic authorities there and sentenced to be burned at the stake along with all of his books. However, Servetus escaped and fled, planning to go to Naples (Giordano Bruno country). For reasons unknown (and indeed unfathomable), Servetus decided to travel to Italy through Geneva, and even attended there a sermon by Calvin. He was recognized, arrested, thrown into prison, and tried for heresy, this time in a Protestant court, and again condemned to death. From this sentence he did not escape, and he was burned at the stake, with his books for fuel, on Oct. 27, 1553. As a consequence of the double burnings (Servetus's French sentence had been carried out in absentia), the Restitutio was never circulated, and his achievement as the discoverer of pulmonary circulation was not recognized until the book was reprinted in 1790.

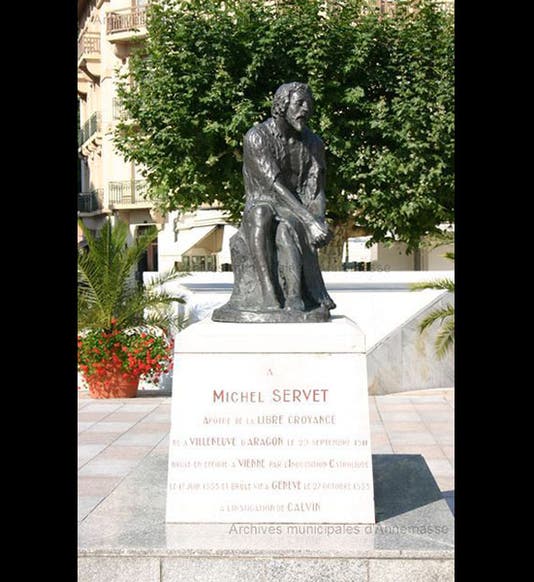

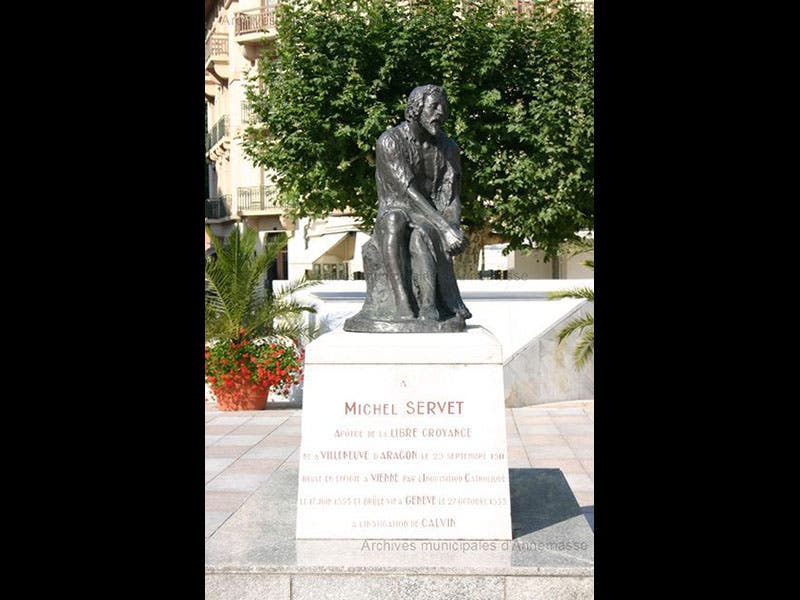

For someone who was virtually unknown for three centuries, Servetus has quite a following today. There is a Michael Servetus Institute in Villanueva de Sigena that commemorates and promotes his work, and there are all manner of monuments scattered about, which is a good thing, since his books are practically nonexistent. In 1903, the authorities in Geneva commissioned a bronze statute to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the death of Servetus, but after it was completed, Calvin sympathizers in Geneva engineered its rejection, and so it was given to and erected in the nearby French town of Annemasse. We see above a pre-war photo of the statue of an imprisoned Servetus (second image). The statue was melted down during the Second World War, but the original molds were discovered and the statue was recast in 1960, and you can see it there today (first image), should you by chance find yourself in Annemasse. Geneva has had to settle for a memorial stone (third image).

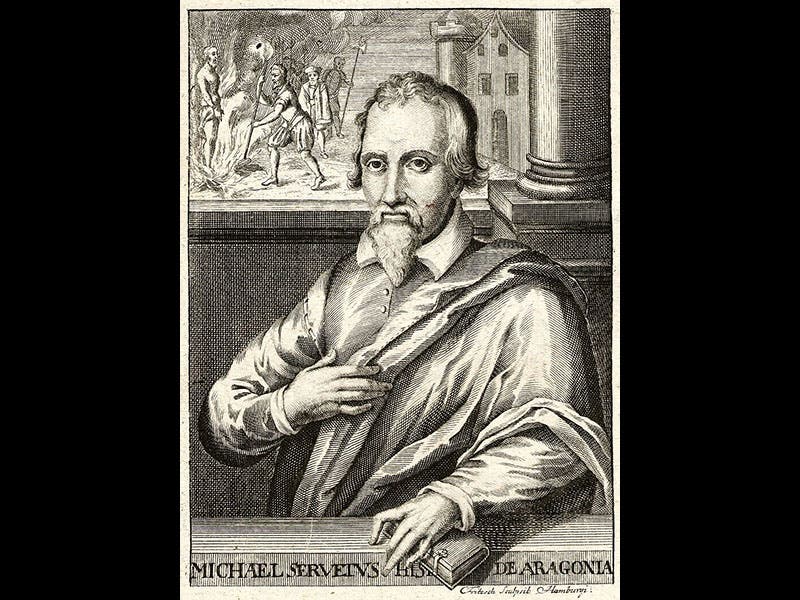

There is an engraving of Servetus and his immolation, first published in 1727, that was supposedly based on a contemporary portrait, so these may indeed be the features of Servetus, one of medicine’s few martyrs (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.