Scientist of the Day - Michael Stifel

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Michael Stifel, a German mathematician and clergyman, died Apr. 19, 1567; his birthdate is unknown. Stifel started out as a monk at an Augustinian monastery in Esslingen, and then was caught up in the German Reformation, taking the side of Martin Luther, who became a good friend. Stifel spent 12 years as a minister in a town near the University of Wittenberg, a school presided over by Philip Melanchthon, Luther's right-hand man. These 12 years of relative peace and quiet allowed Stifel to develop his understanding of mathematics, especially algebra. He published a book in Latin on algebra, Arithmetica integra (1544), and then another in German two years later, Rechenbuch von der Welschen und Deutschenn Practick (1546), and several others. We have the two named books in our History of Science Collection.

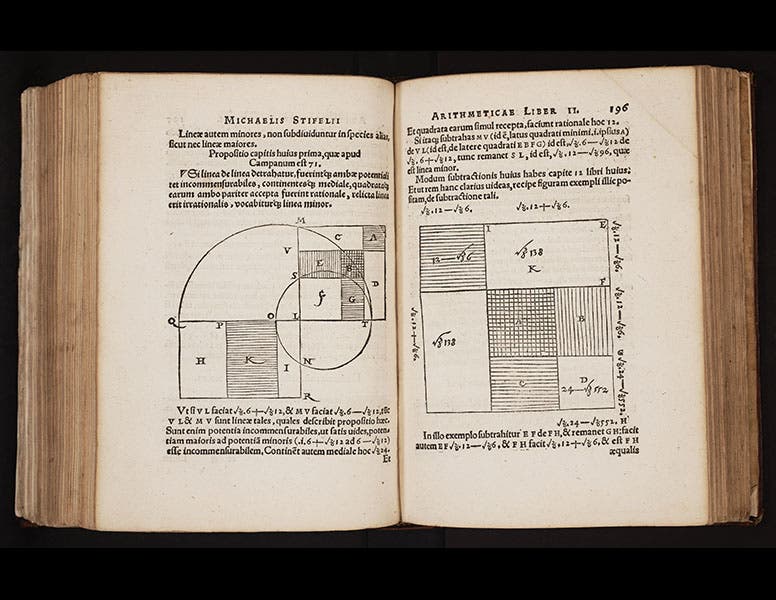

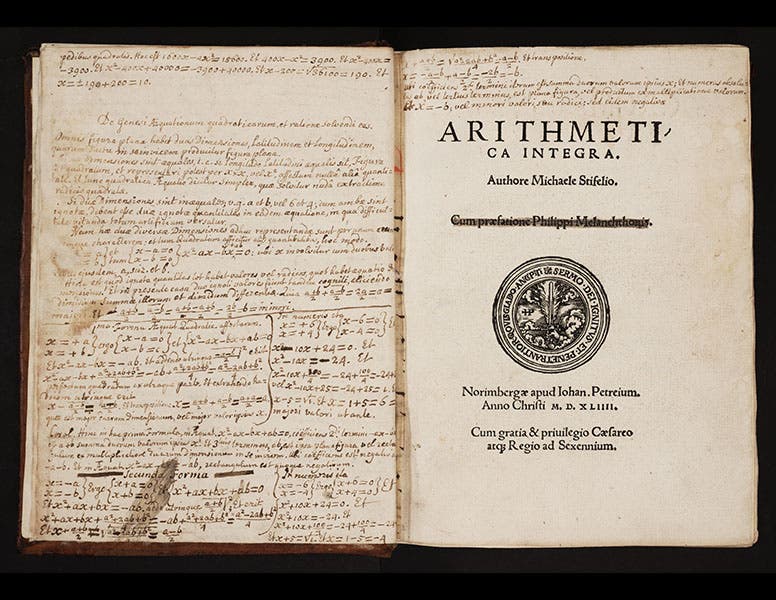

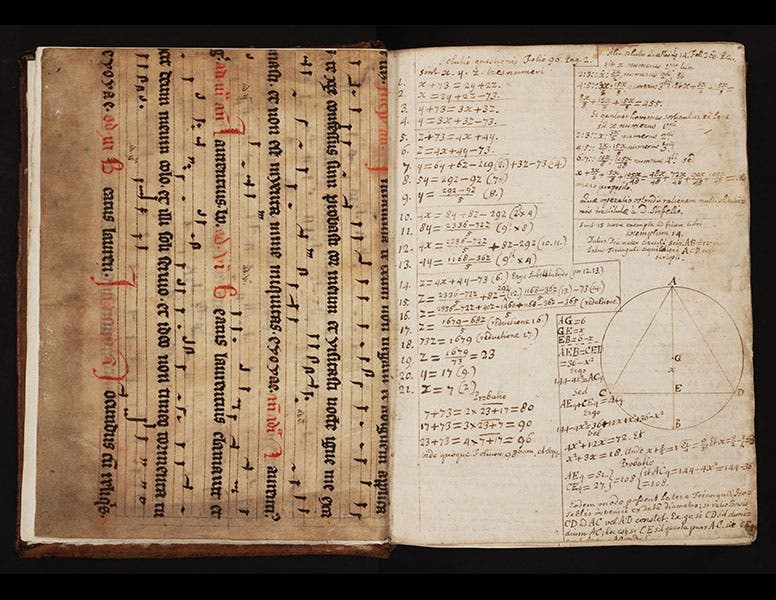

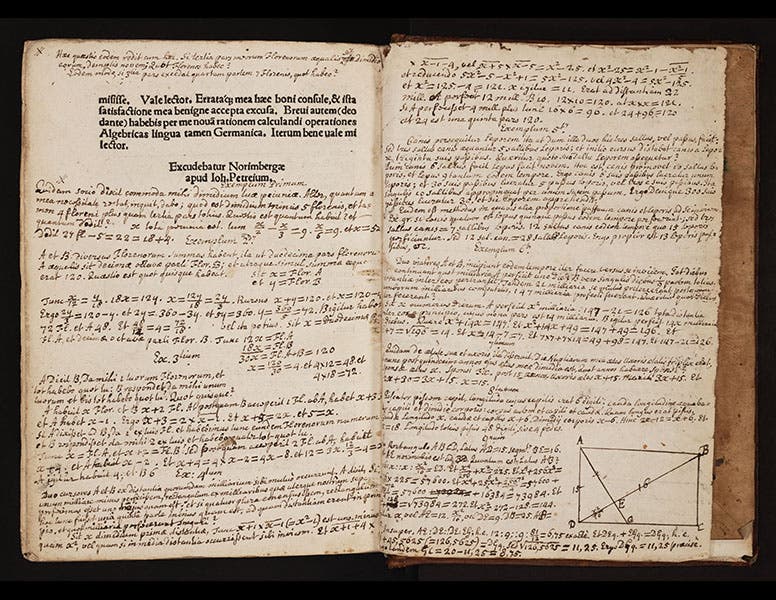

We feature today our copy of the Arithmetica, because it was heavily annotated by an early user, who took great pleasure in working out all the problems on the endpapers. The reader was apparently not a Lutheran, as he carefully lined out Melanchthon's name on the title page. Here is a book just waiting for a scholar of early modern mathematics to examine. Notice that in a previous binding, the book had endpapers fashioned from a musical manuscript (third image); both papers have been preserved in the calf rebinding, awaiting a musicologist's scrutiny.

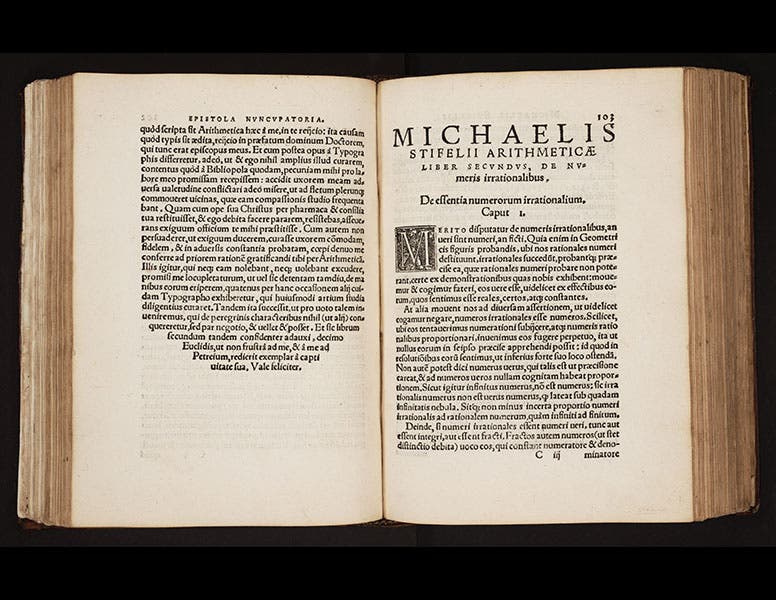

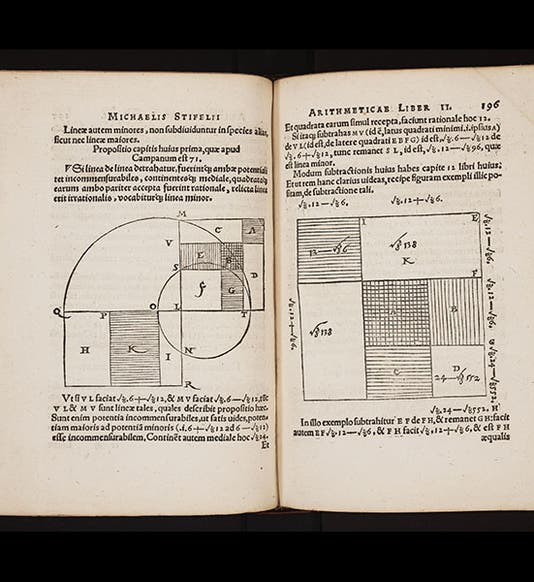

The Arithmetica was published by Johannes Petreius of Nuremberg, who was the foremost publisher of scientific and mathematical treatises in all of Germany, if not Europe. Just the year before, Petreius had published the De revolutionibus of Nicolaus Copernicus. Indeed, the small illustrated initial letters used to begin the chapters in Stifel's book (fourth image) are the very same ones that begin the chapters in the Copernican book, as one of our former fellows, Karl Galle, pointed out to us. How, one wonders, did Stifel happen to land Petreius as his publisher? Stifel had no track record as an author, so why did Petreius take a gamble on him? How did Petreius even know about Stifel? One might suspect that Georg Joachim Rheticus, the Wittenberg mathematician who brought the Copernicus manuscript to Nuremberg, might have had something to do with this.

All this is just by way of pointing out that every author, and every book, brings with it a pocketful of mysteries, and sometimes it is more interesting to catalog what we don't know about a subject that what we do know. In this case, there is a great deal waiting to be discovered.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)