Scientist of the Day - Salomon Andrée

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

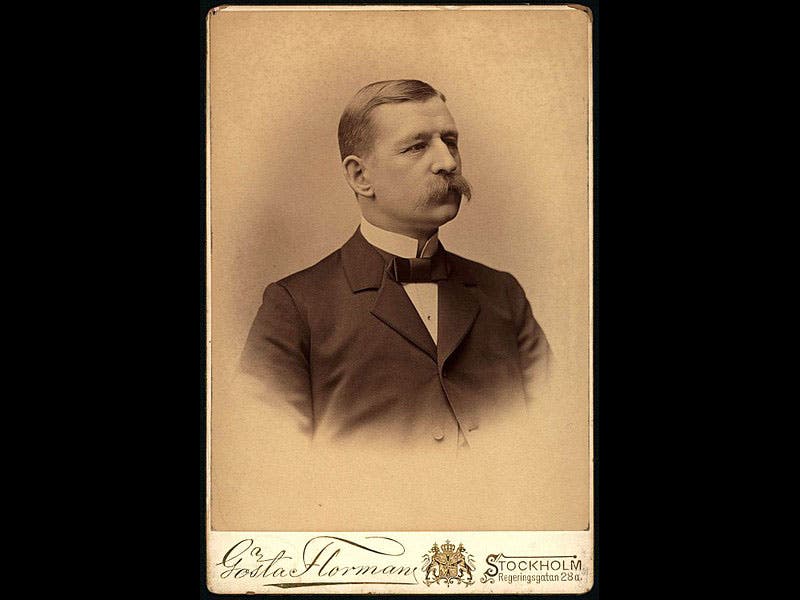

Salomon Andrée, a Swedish balloonist, was born Oct. 18, 1854. On July 11, 1897, Andrée and two fellow Swedes set off in a hydrogen balloon from Danes Island, in the Svalbard archipelago, an island group belonging to Norway that lies about 400 miles north of Scandanavia and north of the Arctic Circle as well. Their goal: to fly over the North Pole. It was one of the most foolhardy polar expeditions ever launched, and no one to this day can figure out why Andrée did not admit that the flight had no chance of success and call it off. Most likely, pride stood in his way--he had the enthusiastic backing of the Swedish government and Alfred Nobel; the planning made him a public celebrity; and he probably just found it easier to go on than to admit that the whole enterprise was simply not feasible.

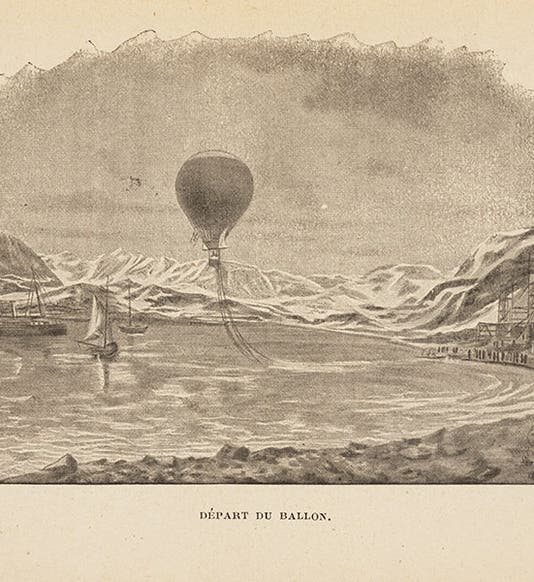

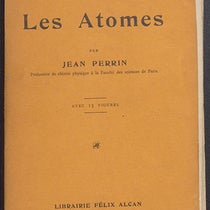

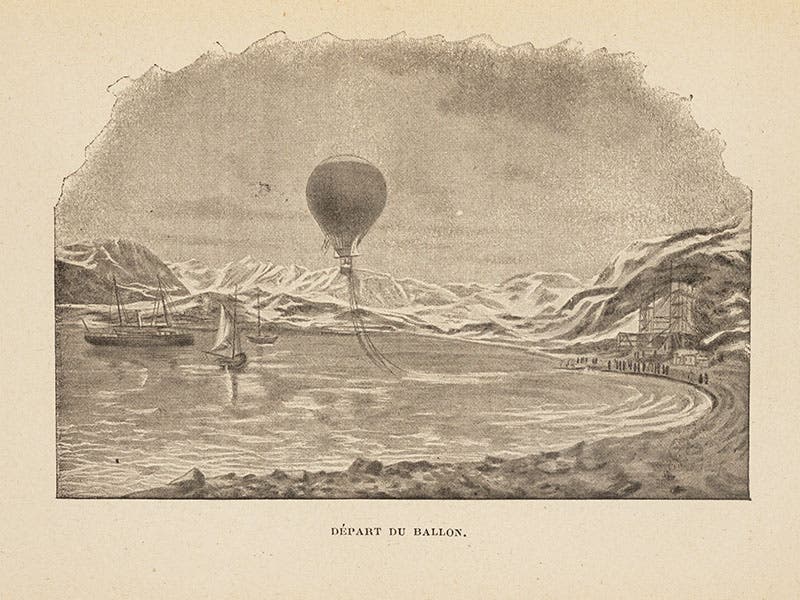

The balloon, named Örnen (the Eagle), was fabricated by a Parisian manufacturer and would supposedly be able to survive the brutal temperatures it would encounter. A special hangar for inflating the balloon was built and shipped to the launch point, which lay north of Spitsbergen. Above we see a wonderful Photochrom print made of the hangar and balloon in 1897 (third image). Andrée intended to steer the craft with long ropes that would drag on the ice and provide a modicum of control. But immediately after takeoff (first image), they lost two of the three guide ropes, and since each rope weighed half a ton, the balloon shot up to high altitude, where the seams froze and started leaking gas. They should have given up and landed at once, but Andrée went on. They drifted northward for three days and three hundred miles before the balloon sank to the icepack, never to rise again. Had wireless been invented, Andrée could have been the first to radio back to base: “Örnen har landat-- the Eagle has landed”.

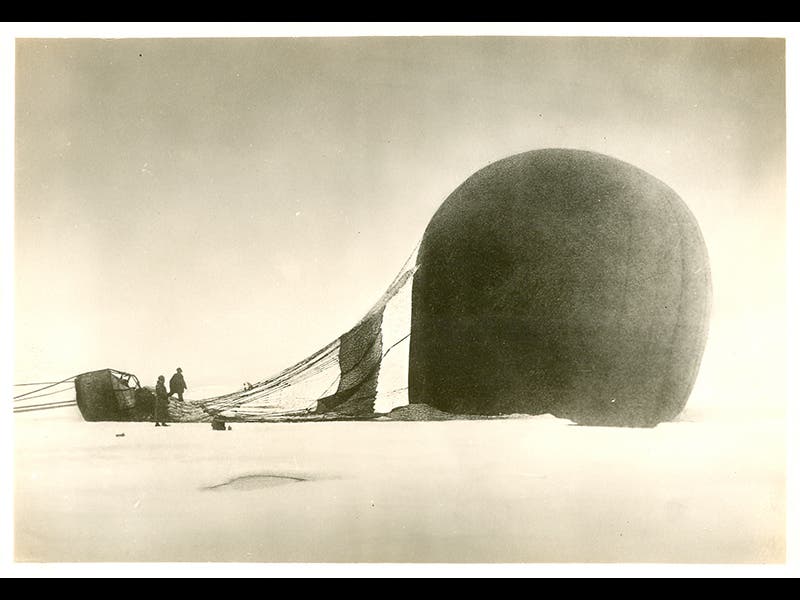

The men had plenty of survival equipment on board, including sledges, and they tried to get back to civilization on foot, but they were not explorers. After two months of sledging and drifting on the pack, they reached land, another small island in Svalbard. But within a short time, one man died and was buried, and soon thereafter, the other two, including Andrée, froze to death in their tents. A modern map (fifth image) traces their wanderings. No one back home knew what had happened--they just knew that the expedition had been lost. Thirty-three years later, in 1930, their last camp was found, and the bodies were recovered and taken back to Sweden for ceremonial burial (sixth image). Also found were five exposed rolls of film, taken by Nils Strindberg, the expedition photographer, after the landing and before his own death. The prints can be seen in the Nordic Museum in Stockholm and in the Grenna Museum in Andrée’s home town, which has a permanent exhibition devoted to the Andree expedition. We show above a Strindberg photograph made just after the forced landing (fourth image).

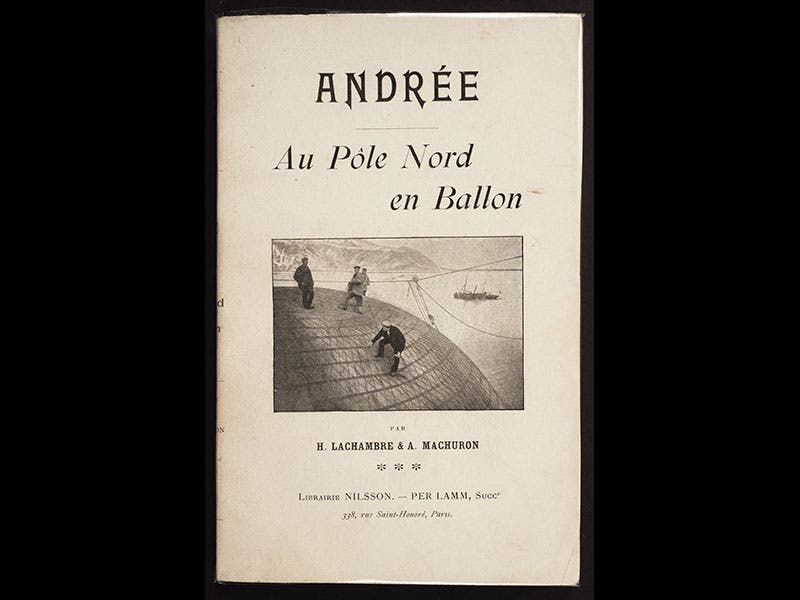

We have in our History of Science Collection a book written by the balloon manufacturer, Henri Lachambre, Andrée: Au pôle nord en ballon (1897) that was published shortly after the launch In addition to its pictorial cover (seventh image), it contains the image depicting the lift-off that introduces the photoset above. The portrait of Andrée (second image) is from a carte de visite.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.