Scientist of the Day - Trajan and Apollodorus of Damascus

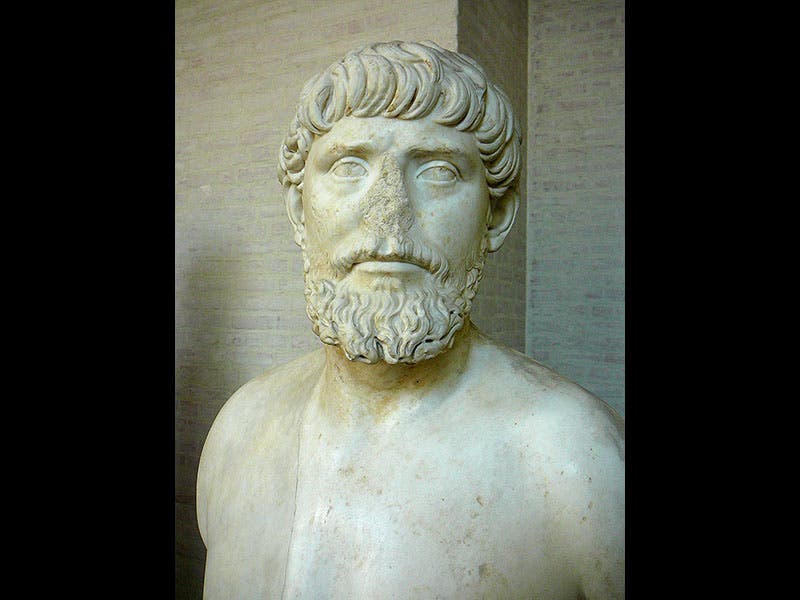

The Roman emperor Trajan was born Sep. 18, in the year 53 CE. There are many busts with his likeness to be found in various museums, all looking, surprisingly, pretty much the same. We show a bust in the Vatican Museums (fourth image). Trajan became Emperor in 98 CE, and from 101 to 106, he waged several wars in what was then called Dacia (corresponding to modern Romania and Moldova). Pursuing the Dacians involved building a massive bridge across the Danube, which led to a Roman victory. The bridge was engineered by a Greek, Apollodorus of Damascus (fifth image), whose dates are unknown, so he is piggybacked here with Trajan.

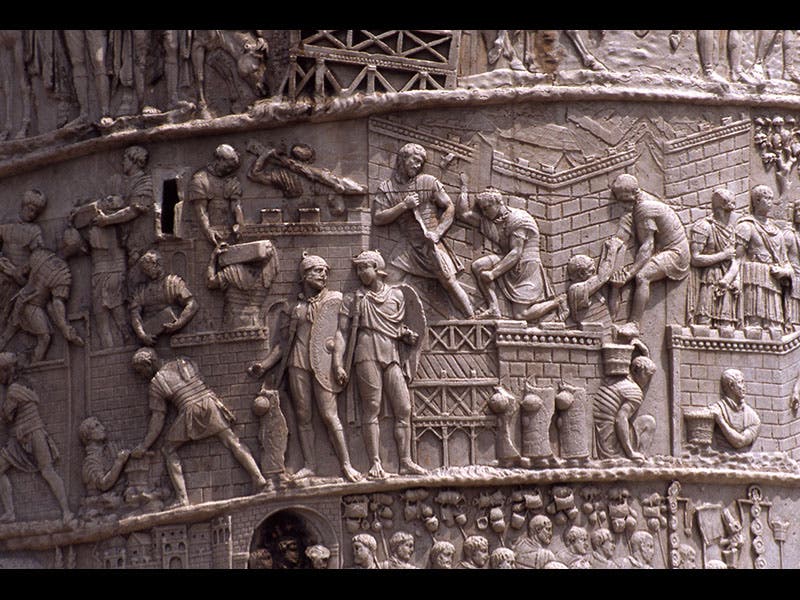

After Trajan and his troops returned home, the Roman Senate commissioned Apollodorus to build a monument to Trajan's Dacian campaign in the part of Rome that would come to be known as Trajan's forum, and Apollodorus did just that (second image). This was an unprecedented style of monument, one that would be much copied in the centuries to follow. It was made of white Carrara marble (the same marble that Michelangelo would later choose for his David), in the form of 20 huge drums stacked one on top of another. Each drum was about 12 feet wide and 5 feet tall, weighing 32 tons apiece, making the column almost 100 feet tall, not counting the base or capital. A long frieze was carved around the column, spiraling up from the bottom, commemorating the Dacian war, and circling the column 23 times. If unwound and spread out--as it is, in plaster, in the Museum of Roman Civilization in Rome--the frieze stretches for 625 feet: One of the scenes shows the Danube bridge, with Trajan at right-center, offering thanks to the gods for his success (third image).

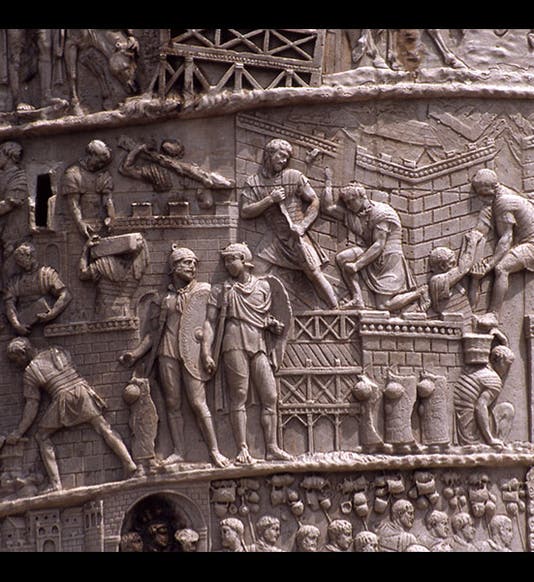

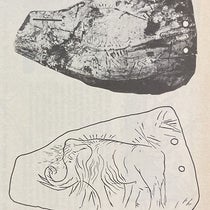

Each drum had steps carved into the center, so when they were stacked, there was a spiral staircase inside, so that it was once possible to climb to the viewing platform on top, although that has not been allowed for a long time. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a replica of Trajan's column in what they call their "Cast Courts"; the column is in two parts, because of the height restrictions (sixth image). Photographs of the frieze, cut up into sections, have been printed several times, most notably in 1900 by Conrad Cichorius; you can see all the sections in thumbnails here. The view of the Danube bridge above comes from this work. The scene showing the construction of a fortress (first image) is a modern photograph.

How Apollodorus erected the column is not known. The Romans did have cranes, but it still would have been difficult to raise such heavy drums to such a height with a crane, so they probably used a tower. The real trick would have been installing the capital, which weighed as much as two drums and had to be lifted over 100 feet in the air. If the account of the moving of the Vatican obelisk in 1586 is any indication, installing the capital would have required thousands of men, many miles of rope, lots of horses, capstans and pulleys, and the air would have been colored, shall we say, caerulean, for miles around. But there is no doubt that the Greco-Roman engineer managed to do it, because the column is there for us to behold, just where it has stood for over 1900 years. It is an amazing accomplishment, however you look at it, one of many perpetuated by those technologically-savvy Romans. And that praise does not even take into account the beauty of the frieze. Trajan should have had no complaints about his monument.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.