Scientist of the Day - Bartolomeo Pitiscus

Bartholomeo Pitiscus, a German mathematician, was born Aug. 24, 1561. Two days ago we celebrated the birthday of a Silesian mathematician, Maria Cunitz. Pitiscus was also born in Silesia, in Grünberg (now Zielona Góra), only about 70 miles from Maria's birthplace in Wołów. Pitiscus however left Silesia to study mathematics in Germany, primarily in Heidelberg, and he never returned to his native soil.

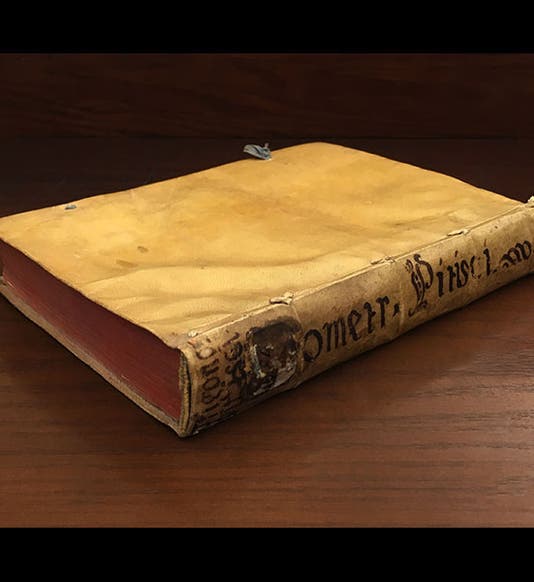

Trigonometry was more or less invented in the 16th century, with Georg Joachim Rheticus providing the first good tables of the trigonometric functions – sines, tangents, etc. Pitiscus was of the second generation of trigonometers, and he published a treatise in 1595 (issued as part of another author's compendium) in which he coined the word trigonometry. Five years later he republished his treatise as a separate book: Trigonometriae siue, De dimensione triangulo[!rum!] libri quinque, item Problematum varioru[!m!] nempe geodaeticorum, altimetricorum, geographicorum, gnomonicorum, et astronomicorum: libri decem… - the first book to have Trigonometry as its title. We have a beautiful copy of this book in our collection, bound in limp vellum (first image), with a fine engraved title page depicting four personifications of the mathematical sciences using trigonometry to further their particular discipline (second image).

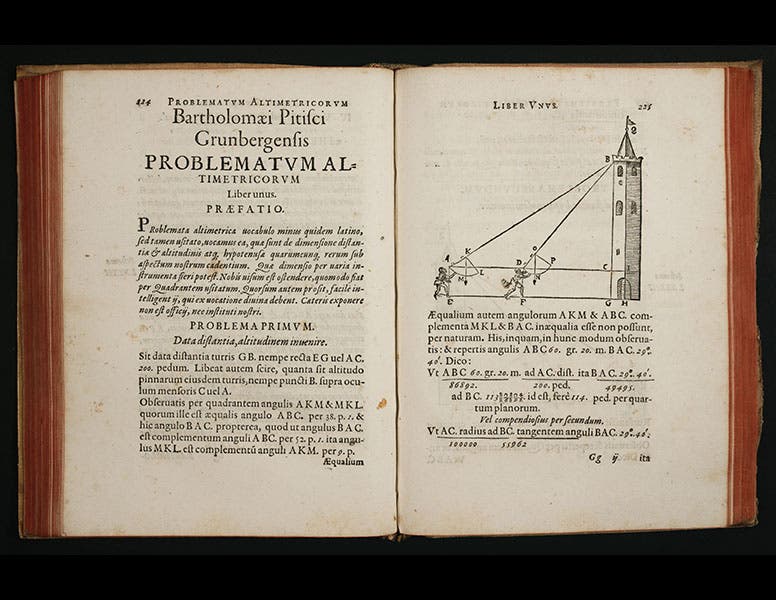

One major section of the book contains trig tables - we show a sample two-page spread below (third image). Note that the sine of 29 degrees and 60 minutes is indeed .50000. Another section provides examples showing how to use trigonometry to measure the height of structures (fourth image).

The last page has an elegant engraved printer’s vignette for the publisher, Dominicus Custos, himself an engraver (fifth image).

There is another feature of Pitiscus’s life that I find as intriguing as his contributions to trigonometry, and that is the fact that he died on his birthday. Aug. 24 appears twice on his tombstone (or would, if we knew where it is). Now, we all have to die on some day, so dying on your birthday is not marvelous, but it is rare. It occurs on the average, as you can well calculate, only once every 365 deaths. It so happens that I have about 7100 entries in my anniversary database. If all these were people, we would expect to have 19 individuals who died on their birthday. However, many of my entries are not people, but spacecraft, locomotives, bridges, fossils, meteorites, and what not, so if we winnow them all out (not easy), we are left with about 3700 historical humans. We would expect to find that 10 of them have coinciding birth and death days. And how many do we actually find? There are nine. They include two writers (Shakespeare and Sir Thomas Browne), a painter (Raphael), and six scientists: Sir Henry Holland (Darwin's personal physician), John Harrison (solver of the longitude problem), Johannes Hevelius (pioneer lunar astronomer and selenographer), Johannes Schöner (Nuremberg astronomer and cartographer, and contemporary of Copernicus), Alfred Wegener (father of continental drift), and our friend Pitiscus. In the spirit of complete disclosure, we should mention that Shakespeare's birthdate of Apr. 23 is merely traditional (i.e, it is undocumented), and Wegener didn't really die on his birthday, he just disappeared in the icy landscape of Greenland on that day, to be found, 5 months later, frozen stiff. He is however counter-balanced by Lawrence Oates, who walked out of Robert Scott's Antarctic tent in 1912 on the day before his birthday, with the famous words: "I am just going outside and may be some time." If "some time" was more than a few hours, he might have made it to his birthday and to our list. But that would not have been a great way to celebrate.

If you look up "birthday effect" on Google or Wikipedia, you will discover that there is a substantial body of literature investigating the possibility that more people die on their birthday than probablility statistics would predict. Our figures suggest that there is no birthday effect whatsoever among those of a scientific persuasion.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)