Scientist of the Day - Haakon Shetelig

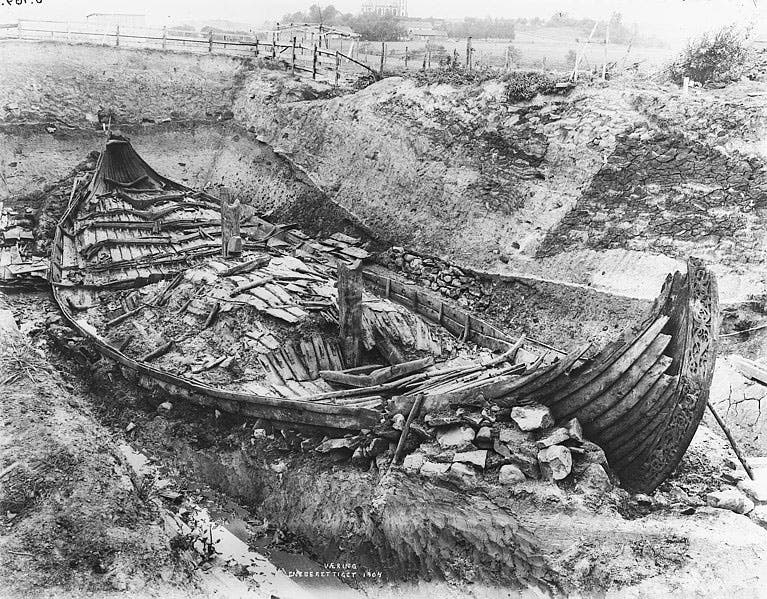

Haakon Shetelig, a Norwegian archaeologist, was born June 25, 1877. In 1904, Shetelig and a Swedish collaborator, Gabriel Gustafson, unearthed, in Oseberg, Norway, the most signficant Viking burial mound ever discovered. The star occupant of the mound was a full-fledged Viking longship, which is now in the Viking Ship Museum on Bygdøy, in Oslo.

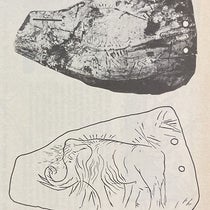

The Oseberg ship is just over 70 feet long and almost 17 feet across. It was made of oak and clinker-built, meaning that the side boards (strakes) overlap and are secured by iron rivets. There are 15 oar holes on each side, indicating the ship was powered by 30 oarsmen, assisted by sails attached to the central mast. The construction of a Viking longship was an incredible feat, considering that the only tools available were long-handled axes for felling; wedges, froes, and hammers for splitting; short-handled broadaxes for sizing and smoothing; a dado plane for grooving the strakes, and a forge to make the rivets. You can see the strakes and the rivets in the first detail below (third image). There is no evidence that saws of any kind were used in felling trees or constructing the ships. Each strake had to especially shaped with lots of bends and recurves. In addition, parts of the ship were decorated with intricate carving (fourth image).

Modern dendrochronology indicates that the ship was built in 834 C.E., so it is older than the Gokstad ship, another famous Viking longship that is also housed in the Viking Ship Museum. The honoree was a woman, a queen apparently, but which queen is the subject of some debate.

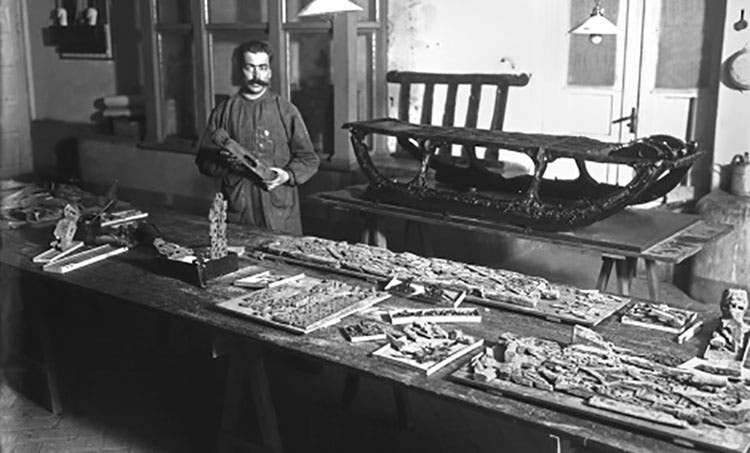

Also found with the ship, in addition to human remains, were several sledges (fifth image), a carved bed, a carriage, and numerous smaller items. These wooden objects began to deteriorate soon after being uncovered, and so they were preserved by being soaked in alum, which stabilized the wood, and were then coated with lacquer (sixth image).

Ninety years later, it became apparent that the wooden objects had seriously deteriorated, and that the cellulose in the wood had been almost totally destroyed by the alum, so that many of the artifacts are held together only by the lacquer – there is no wood left. This has always been the bane of conservation efforts in all sorts of fields – what one generation does to preserve things becomes, to the next generation, the worst of all possible actions. Which is why modern conservators, if they can, like to leave things alone, to avoid doing irreparable damage, even with the best of intentions. The Viking Ship Museum is working hard to find a solution to the alum problem.

Shetelig, to get back to our birthday subject, is also noted for introducing the idea that the Viking era began when the Norsemen invaded the English tidal island of Lindisfarne in 793 C.E. and laid waste to the monastery and quite a few of its monks. Many Viking scholars agree, and just as many get apoplectic at the very suggestion, believing that the Viking Age began earlier in the 8th century. Not being a Viking scholar, I am happy to have no opinion on the matter.

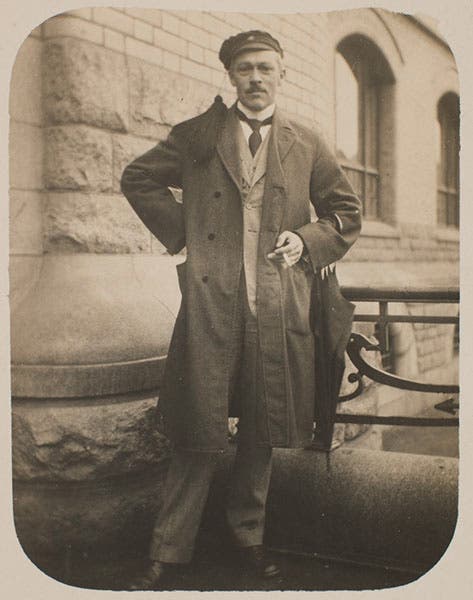

There is a nice photograph of 1904 that shows Shetelig’s partner, Gabriel Gustafson, at work on the ship excavation with a large crew, but Shetelig is not present. So we will settle for this one of Shetelig all by himself (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.