Scientist of the Day - Heinrich Biber

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, a Bohemian violinist and composer, was baptized on Aug. 12, 1644; his date of birth is unknown. Biber is often considered one of the best violinists, and THE best composer for the violin, of the 17th century. We don't ordinarily celebrate violinists here, even very good ones; Biber attracts our attention because he wrote a piece of music drawn from, or at least inspired by, the great Jesuit scientist Athanasius Kircher, who was a Scientist of the Day three years ago. Kircher wrote books on every possible subject – optics, magnetism, cosmology, geology – including an encyclopedia of music, the Musurgia universalis (1650). Music, we should recall, was considered a mathematical art, and had been lumped in with arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy as part of the liberal-arts quadrivium, ever since the first universities were established in the West around 1200. So it was quite appropriate that Kircher should have written a compendium on music.

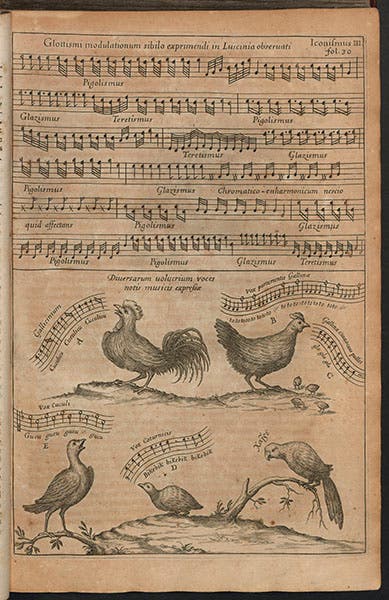

What attracted Biber to Kircher was a short section where Kircher discussed bird songs. Kircher was fascinated with the nightingale and wrote down, in musical notation, all the variations of Nachtigalllieder he could record, as we see in the top half of a full-page plate that appears quite early (p. 30) in his very long folio (fourth image). Kircher noted, admiringly, that the nightingale can sing not only diatonically, but also chromatically and enharmonically. On the bottom half of the plate (see detail, first image), Kircher recorded the songs of a cock, a hen with chicks, a cuckoo, and a quail. In addition to the musical notation, Kircher provided lyrics, such as cuculicu for the cock and bikebik for the quail. For a coda, Kircher offered us a parrot that could say “Hello” in Greek (chaire).

Apparently Biber encountered this plate, or was directed to it by someone at court, and thought he would write a piece for violin based on these bird songs (with a frog and a cat thrown in for good measure). The result was the Sonata representativa, written in 1669. It is just 9 minutes long, and you can listen to a recording on YouTube which shows a scrolling score as well. The nightingale (Die Nachtigal) sings at the 1:54 mark (measure 38), the cuckoo at 3:15 (m. 64), the hen and cock at 5:07 (m. 113), and the quail (Die Wachtel) at 5:42 (m. 135). The Greek-speaking parrot did not get a singing role, unfortunately.

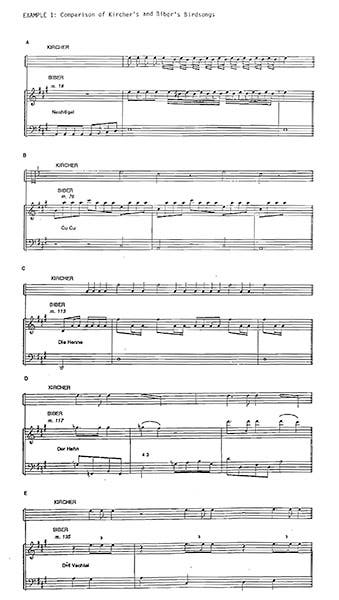

There has been some discussion among musicologists as to whether Biber really knew about Kircher's book and copied his songs directly, or was just inspired by the idea of playing bird songs on the violin, but some years ago, Charles Brewer, in a short article on the “Sonata Representiva”, compared Biber's score with Kircher's bird songs and found a rather close correspondence between the two. We reproduce here Brewer's comparison, and you may judge for yourself (fifth image). Of course, there are many more measures in Biber’s sonata than Kircher provided, so much of Biber’s composition has to be original, but it does seem that he started with Kircher’s tunes and expanded upon them.

Brewer has since written an entire book about Biber’s era (The Instrumental Music of Schmeltzer, Biber, Muffat and their Contemporaries, 2016); whether he has changed his mind, we do not know, since, this post notwithstanding, we do not acquire books on instrumental music for our Library. But the book is available on Amazon, and we note from the photo of the book (sixth image) that Kircher's plate showing bird songs is splayed prominently across the cover, so most probably Brewer is sticking to his guns.

Instances of a book of science directly influencing a performing or visual artist are much scarcer than one might think. We can recall only two others (although certainly there are more): Lodovico Cigoli’s painting of a cratered moon in his Assumption of the Virgin, inspired by Galileo’s lunar engravings in Sidereus Nuncius, about which we have written in these posts, and Esprit Jouffert’s book on four-dimensional geometry and its impact on Pablo Picasso, a discussion of which awaits Jouffert’s birthday, next Mar. 15. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)