Scientist of the Day - John Rennie the Elder

John Rennie, a Scottish civil engineer, was born June 7, 1761. Sometimes called "the Elder," to distinguish him from his engineer son John junior, Rennie designed canals from the 1790s on, during the golden age of canal building in England, and made his initial mark with his aqueducts, which carried canals across rivers or other canals. These are fascinating structures, bridges for carrying streams over streams; a graceful example would be Lune Aqueduct near Lancaster, which carries the Lancaster Canal over the River Lune (first image).

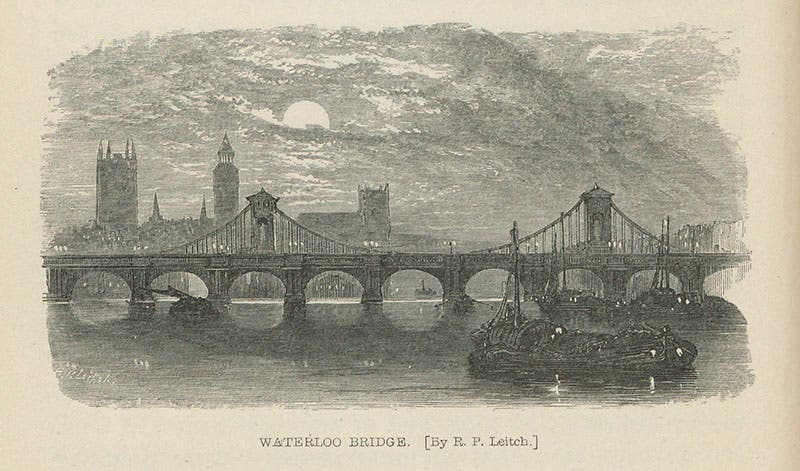

Rennie then began designing bridges; the Waterloo Bridge over the Thames in London, opened in 1817, was his handiwork. We see here the centering under one of the arches of the bridge under construction, and the completed bridge (second and third images).

But Rennie’s most famous bridge has to be the New London Bridge, designed by Rennie but finished after his death by his son John in 1831. The Old London Bridge truly was falling down, and its narrow arches made river travel difficult, so Rennie's bridge, with its five wide graceful arches, was a welcome and pleasing replacement. Our view of the finished bridge (fourth image), like all our other views so far, comes from Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers, 1861, which has a healthy section on Rennie and his work.

If you would like to see the New London Bridge yourself, you do not need a passport; you can find it now at Lake Havasu City in Arizona. John McCulloch, the entrepreneur who built this retirement community in the desert, purchased the bridge in 1968, after the London authorities had decided to replace it, and shipped it stone-by-stone to Arizona, where it was rebuilt. It is not truly identical to the original bridge, since it now has concrete innards, but it looks the same on the outside, although the setting seems a bit odd (fifth image).

All of the stones were carefully numbered before the original bridge was dismantled, so that it could be accurately re-erected, and while most of the numbers were removed, some of them can still be seen, if you look carefully (sixth image). Fortunately, John Rennie’s grave was allowed to remain at its original site, in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

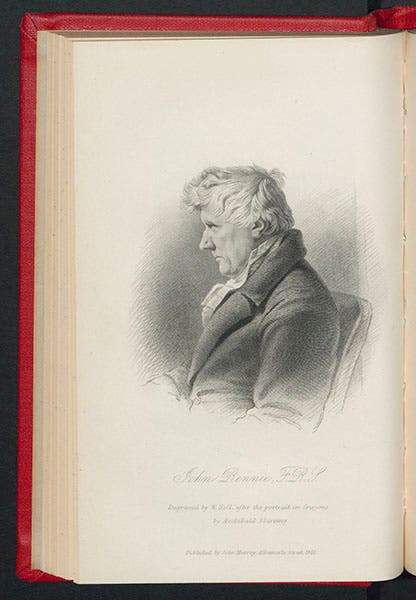

Smiles wonderful Lives of the Engineer has not only lovely engravings of many of Rennie’s projects, but a splendid engraved portrait, done after an original crayon sketch by Archibald Skirving (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)