Scientist of the Day - Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, was born Mar. 13, 1741. He is best known to the modern public as the enlightened ruler who commissioned Mozart's The Abduction from the Seraglio in 1781, and who then complained to Mozart (if the film Amadeus (1984) be our guide) that there were "too many notes" (to which Mozart supposedly replied, "there are just as many as are required"). In addition to the roles, real and imagined, that he played in Mozart’s musical life, Joseph also crops up several times in the history of Enlightenment science. Two months ago, we featured Wolfgang Ritter von Kempelen as our Scientist of the Day. Von Kempelen was an Austrian inventor who built a chess-playing automaton called "The Turk". He presented it to Empress Maria Theresa of Austria in 1770, but it seems to have been put away and forgotten. Joseph succeeded his mother Maria Theresa in 1780, and one of his first acts as sole Emperor (or Kaiser) was to ask von Kempelen to revive the Turk and send it on tour. Which von Kempelen did, and his invention became a public sensation, and remained so long after von Kempelen's (and Joseph’s) death.

At about the same time that he was reviving the Turk, Joseph visited Florence, where his younger brother Leopold was the Grand Duke, and he saw there an elaborate set of wax anatomical models that had been crafted by Clemente Michelangelo Susini. Susini had joined an anatomical modeling workshop in Florence in the 1770s and had risen rapidly to the top. The visiting Kaiser was absolutely blown away by Susini’s models, realizing at the same time how valuable they would be for medical instruction. So Joseph immediately ordered a duplicate set of models – well over 1000 separate items – for the Medical University of Vienna. It took Susini 6 years, but he eventually fulfilled the contract, and the models were shipped by mule train in stages over the Alps and then by boat to Vienna.

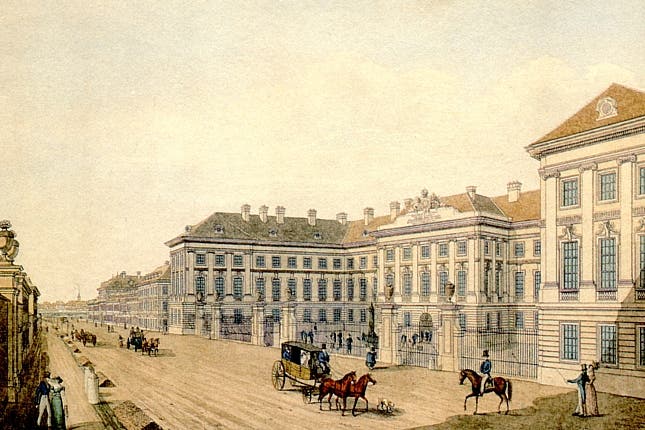

Joseph in the meantime had built a brand new medical academy, the Josephinum, and this became the repository for the models when they arrived. They are still there, 1192 wax models (everyone seems to agree on the count, which is rather amazing) on display in six rooms set aside specifically for them.

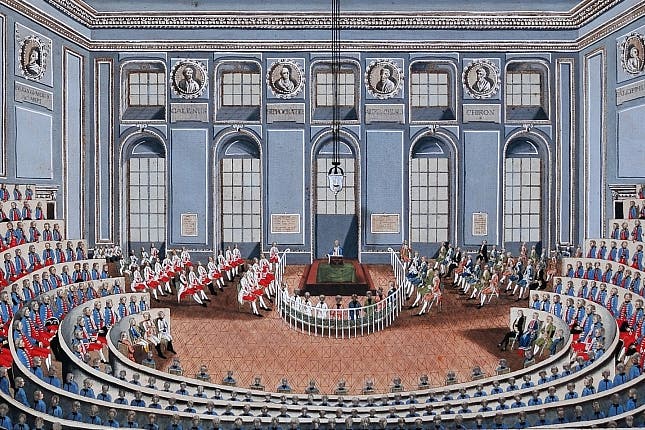

We see here two views of several of the rooms, a detail of one male wax model, the Josephinum as it appeared in 1790, a contemporary look at one of the lecture halls, and a modern photo of the outside of the Josephinum today.

We also provide a link to the most sensational of the Susini models in the Josephinum, the anatomical Venus, which is the first of a number of rotating images on the Josephinum’s home page.

The Josephinum unfortunately has recently closed for renovation, so it may be some years before you can journey to Vienna and see Susini’s creations in the flesh.

The portrait of Joseph is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It was painted in 1775, five years before Susini began his commission, and 15 years before Joseph’s premature death in 1790. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)