Scientist of the Day - William Cavendish

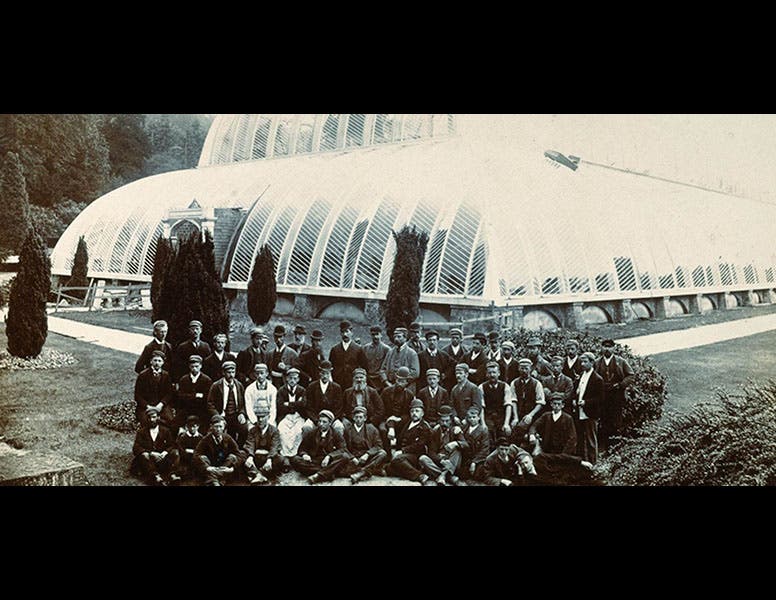

William Cavendish, the 7th Duke of Devonshire, was born Apr. 27, 1808. The Cavendish family was one of the most distinguished (in a peer kind of way) in British history. Before the 7th Duke, there was only one Cavendish who took an interest in science, and that was Henry, and he wasn't in the ducal line of succession, being the eldest son of the third son of the second Duke. But Henry, although he would never become Duke, was a brilliant scientist, discovering hydrogen, and performing the famous Cavendish experiment to measure the mass of the earth. The 6th Duke, also a William, was not himself a scientist, but he hired Joseph Paxton to supervise the gardens at Chatsworth House, the Cavendish family estate in Derbyshire (fifth image). Paxton responded by designing and building the "Great Conservatory”, an immense greenhouse that was, at the time, the largest glass-and-steel structure in the world (sixth image). Paxton would go on to design the next structure that had the honor of being the largest glass building in the world, the Crystal Palace, home of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851.

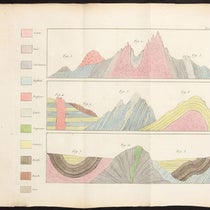

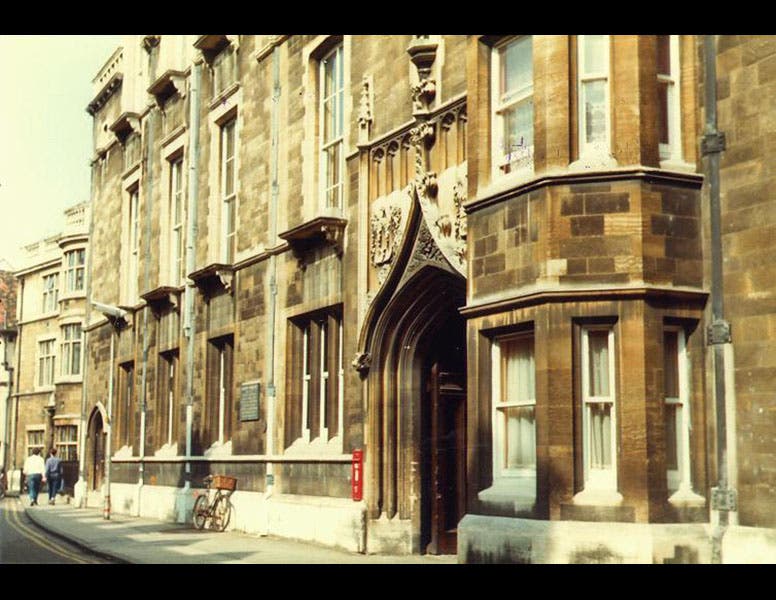

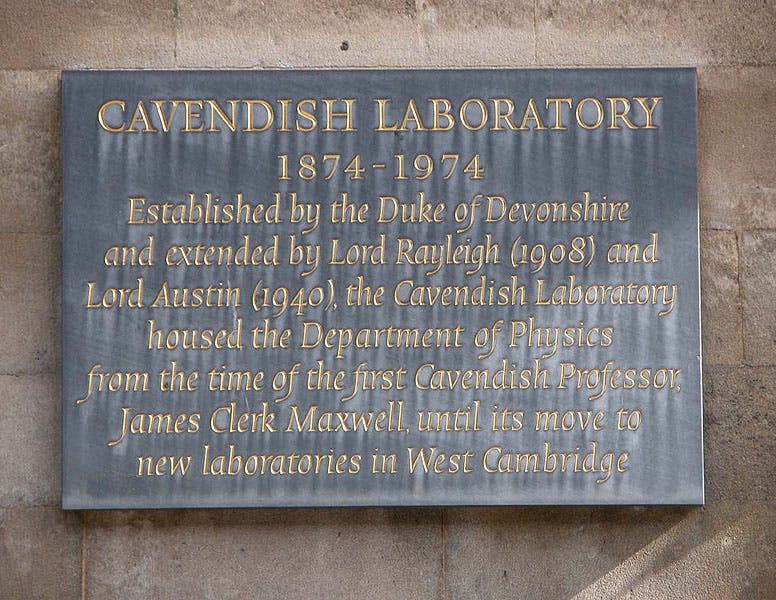

Which brings us to the 7th Duke (first image). This William was not the son of the 6th Duke, but rather a cousin, since the 6th Duke of Devonshire was unmarried and had no children. But William the 7th Duke may have been the most influential Duke of them all. He was chancellor of the University of London for 20 years, and then he held the same position at Cambridge University for 30 more years, from 1861 to 1891. While Chancellor at Cambridge, he provided the opportunity and the funds for Cambridge to build its first physics laboratory, which was called, in his honor, the Cavendish Lab. It was opened in 1874, with none other than James Clerk Maxwell, the founder of the theory of electromagnetism, as the first Cavendish Professor of Physics (second image).

Since its institution, the Cavendish Lab has been the locus of more important scientific discoveries than perhaps any other location in history. It was here that J. J. Thomson discovered the electron in 1897, Ernest Rutherford discovered the nature of radioactivity in 1898, Charles Wilson invented the cloud chamber in 1911 (fourth image), Francis Aston identified the first isotopes in 1919, James Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932, and James Watson and Francis Crick unraveled the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953--all of these discoveries, incidentally, earning Nobel prizes. A centennial plaque was installed on the Old Lab in 1974 (third image). If they offered a Nobel Prize for laboratories, the Cavendish would surely be awarded the first.

When Charles Darwin died in 1882 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, the pallbearers consisted of four scientists and four dignitaries. The scientists were the likes of Thomas Henry Huxley and Alfred Russel Wallace. But the dignitaries were well-chosen as well: James Russell Lowell, the poet and diplomat; Frederick Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby, a sportsman (and the Stanley of Canada’s Stanley Cup); William Spottiswode, President of the Royal Society, and our Scientist of the Day, William Cavendish, the 7th Duke of Devonshire.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)