Scientist of the Day - William Prout

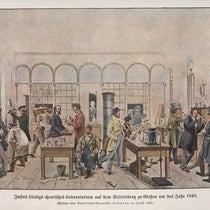

William Prout, an English physician and chemist, was born Jan. 15, 1785. Prout is best remembered for proposing in 1815-16 that the atoms of all the heavier elements are simply aggregations of hydrogen atoms, so that a carbon atom, for example, is just 12 hydrogen atoms crammed together. This idea came to be called "Prout's hypothesis," and it seemed plausible enough, since the weights of many elements, such as carbon, are indeed nearly exact multiples of the weight of a hydrogen atom. However, there are other elements, such as chlorine, that have atomic weights that are not close to being even multiples of hydrogen. Chlorine has an atomic weight of 35.45, so how could it have been formed from hydrogen atoms without cutting one in half? Because of such problems, Prout's hypothesis was generally suspect for nearly a century. It is informative, for example, that in the engraving titled "Distinguished Men of Science in 1807/08", which was printed in 1862 and which we have mentioned several times in these notices, Humphry Davy, John Dalton, Count Rumford, and Daniel Rutherford were all included, but William Prout was not.

Then, in the early 20th century, isotopes were discovered, which solved many of the difficulties with Prout's hypothesis. It turns out that chlorine comes in several different varieties or isotopes with different weights; the more common isotope of chlorine has an atomic weight of 35, while a less abundant isotope has an atomic weight of 37. So when you average them up, you get 35.45. But each individual atom has a weight of 35 or 37; there is no atom that weighs 35.45. Other discrepancies would be resolved by the discovery of the neutron. The neutron is slightly heavier than a proton, so an atom like oxygen, with 8 protons and 8 neutrons, is going, one would think, to weigh more than 16 hydrogen atoms, which essentially consists of 16 protons.

Finally, we learned about nuclear binding energy. It turns out that when your take a number of protons and neutrons and bind them up in a nucleus, it takes considerable energy to hold the particles together, and that energy comes at the expense of mass. No one suspected this until Einstein discovered mass-energy equivalence in 1905. Knowledge of binding energy resolved most of the remaining discrepancies, explaining, for example, why one oxygen atom is actually lighter than 16 hydrogen atoms, when the 8 neutrons should make it heavier.

So was Prout's hypothesis correct? This is a tricky question and will take a philosopher of science to answer properly, which we are not. Prout didn't know about isotopes or nuclear binding energy, and he didn’t know about protons and neutrons – all of this understanding was a full century in the future. But if the essence of Prout's hypothesis is that atoms are made up of smaller fundamental units, and that the units are the same in all atoms, differing only in number, then Prout was really pretty close to the mark.

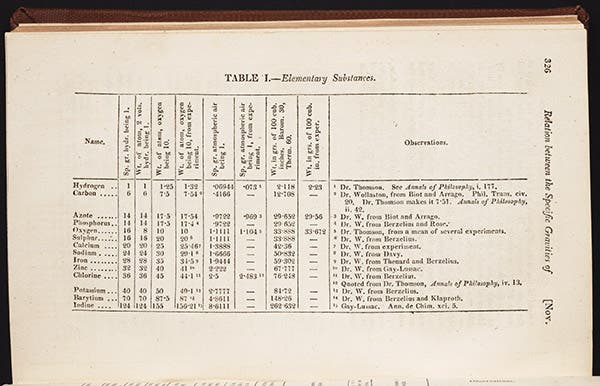

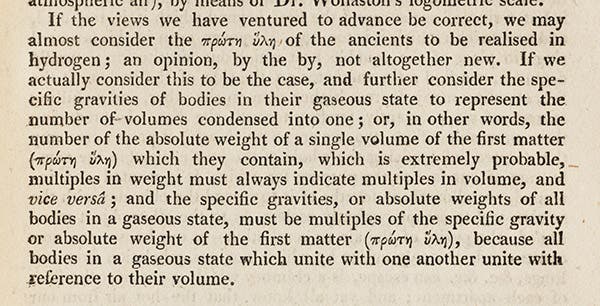

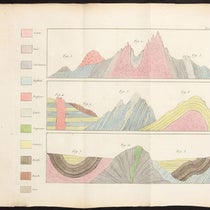

Prout announced his hypothesis in two papers that were published anonymously in the Annals of Philosophy in 1815-16. Annals of Philosophy was a journal that was launched by the chemist Thomas Thomson in 1813 to fill a need; it was published once a month religiously for 13 years, and then bought out and shut down in favor of another journal in 1827. There are thousands of scientific journals like this, with short runs and small circulations, but often containing important and sometimes seminal articles, and one of the strengths of the Linda Hall Library is that we have most of these minor journals in paper form in our vast serials stacks. So I was able to walk down a long aisle, retrieve the two volumes with the Prout papers, and get them scanned for this piece. We show the first page of the first paper (second image) a table from the first paper (third image), and the last page of the second (fourth image), where Prout's hypothesis is stated for the first time, in these words: “If the views we have ventured to advance be correct, we may almost consider the prime matter of the ancients to be realised in hydrogen; an opinion, by the by, not altogether new."

There seem to have been two contemporary portraits of Prout; we show the one painted by Henry Marriott Paget that is now in the University of Edinburgh Fine Art Collection (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.