New Acquisition: Tractatus Astrologicus

![Handwritten astrological computations, in two different pens or hands, on a slip of paper inserted into the Library copy of Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)]](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e078e60d-4cde-474e-b4ad-29ee3465860e/Image-1-3364_0057.jpg?w=1000&h=715&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Handwritten astrological computations, in two different pens or hands, on a slip of paper inserted into the Library copy of Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)]

Astrology is not a science by today’s standards. However, since astrological predictions depend on the calculation of planetary positions, early modern European astronomy and astrology developed together. Astronomers like Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler, seeking political favor, cast astrological predictions for their patrons. Astrology relied on careful study, scrupulous calculations, and a good dose of political savvy—and with luck, practitioners left written records of all three components, perhaps within an astrological book. One such book, a heavily-annotated copy of Luca Gaurico’s Tractatus astrologicus (Astrological tracts), was acquired by the Library in October of 2023 at the Boston Antiquarian Book Fair, from the London-based bookseller Sokol Books.

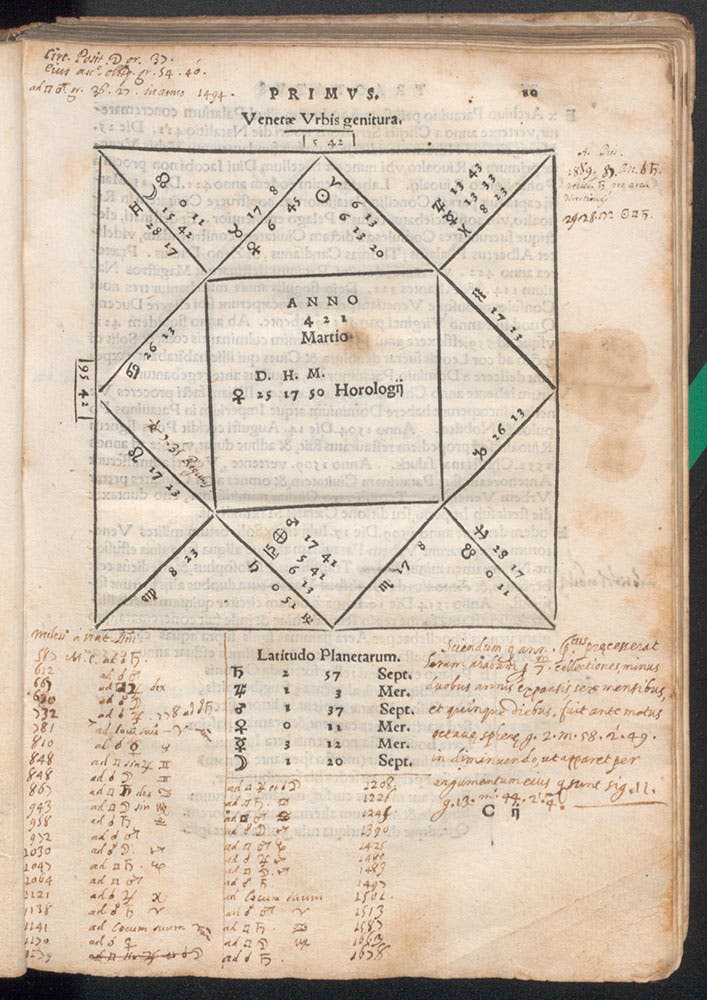

Horoscope for the city of Venice, “born” (founded) in March 421, with extensive annotations, in Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)

Tractatus astrologicus is a book of judicial astrology. This branch of astrology studied humans’ fates as influenced by the stars and planets. Luca Gaurico (1475-1558) was an Italian astronomer and astrologer who worked in the service of influential political and ecclesiastical figures like Catherine de Medici and Pope Paul III, and the Tractatus was his most popular work. It contains almost two hundred horoscopes of major cities and buildings, members of the Catholic clergy, monarchs, aristocrats, scholars, and theologians.

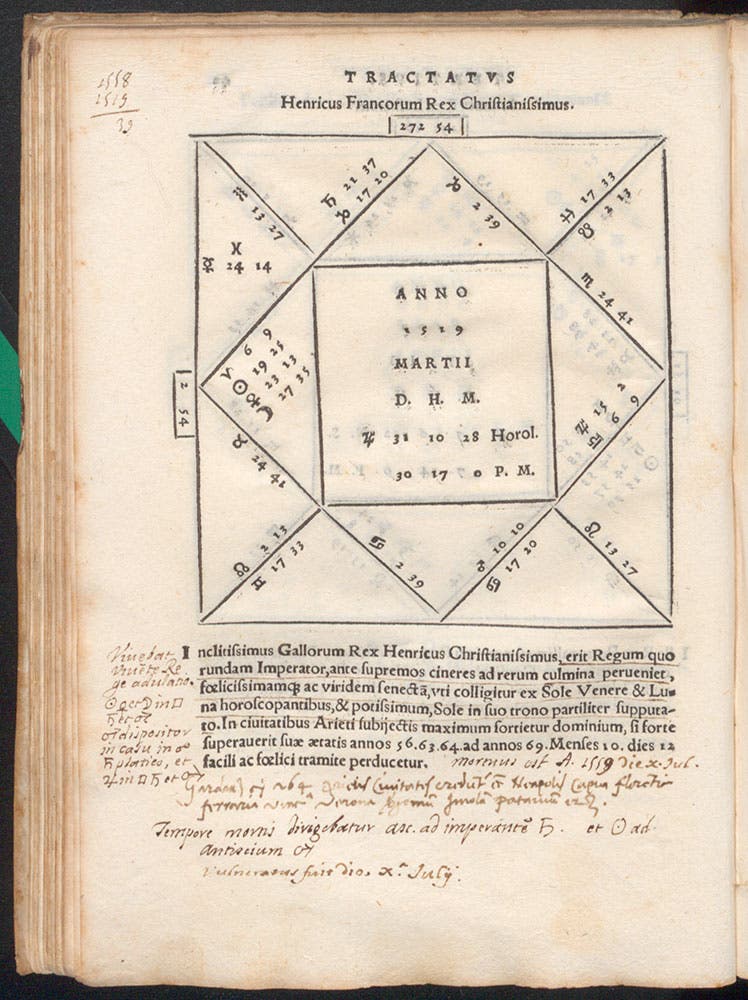

Horoscope for Henry II of France, born March 1519. Gaurico predicts that the King will lead a long and happy life if he lives past the ages of 56, 63, 64, and 69. Unfortunately, Henry II was wounded in a tournament and died in 1559, seven years after Tractatus was published, at the age of 40. In Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)

Each horoscope includes a geniture, or birth chart, and a short biography summarizing astrological predictions, including achievements, illnesses, and death. These look different from the birth charts we see today, which are usually drawn as circles divided into twelve segments. Gaurico’s genitures are made of straight lines interlocked into squares and triangles. The triangles represent the twelve houses of the sky, which are aligned with the Sun’s movement through the sky as seen from the Earth. The first house is at the 9 o’clock position, and the houses proceed in a counterclockwise direction. He places symbols for the planets, Zodiac constellations, and the “head and tail of the dragon,” which is where the moon crossed the ecliptic, in the sections of the sky where they had appeared at the time of birth. Gaurico then uses these placements to discern the life of the person or place in question.

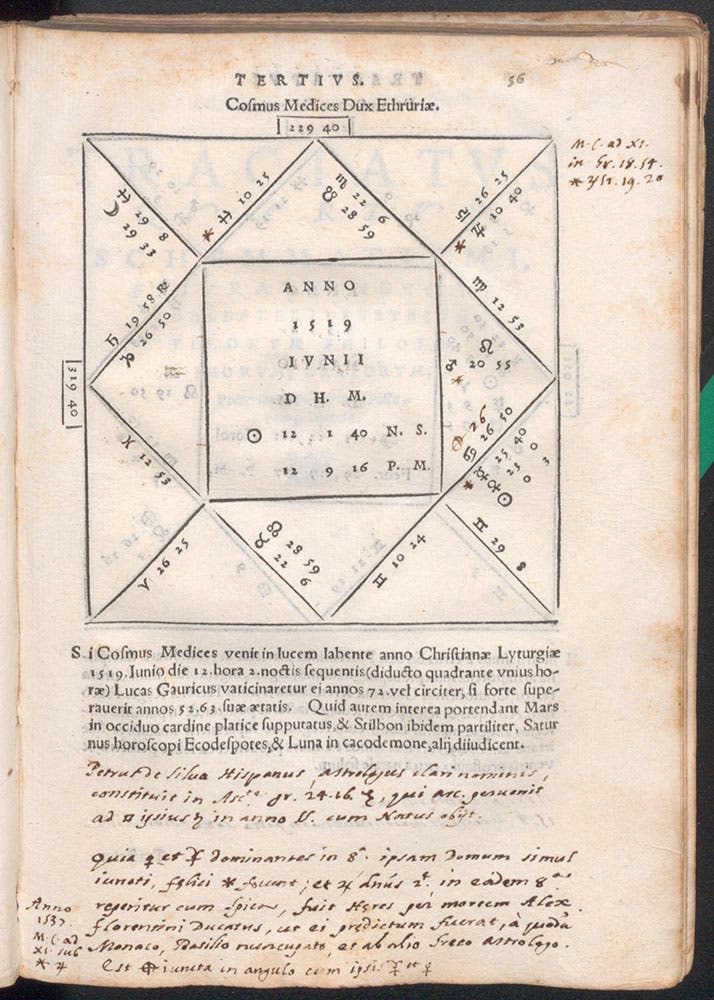

Horoscope for Cosimo I de’ Medici, born June 12, 1519, in Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)

In the page shown above, Gaurico gives the horoscope of Cosimo I de’ Medici, born June 12, 1519. He predicts that Cosimo I will live to be 72 years old “or thereabouts,” if he makes it to 52 and 63 years of age. He notes significant placements: Mars and Mercury at the western point, Saturn in the ecodespotes (Greek oikodespotes, or “house-master”), and the Moon in cacodemone, or twelfth house. However, he leaves the specifics of Cosimo I’s life for other astrologers to judge.

A century later, three other astrologers did. The Library copy of Tractatus astrologicus has three names written in it. Several of the annotations are signed “Th. Oderico.” These annotations were written by Tommaso Oderico, a Genoese astronomer, astrologer, and horoscope and almanac author active between the 1640s and the 1660s. The title page has the name of Francesco Maria Spinola, a Genoese aristocrat and astrologer active at the same time. While Spinola didn’t sign any of his annotations, the handwriting in his signature closely resembles the annotations to the city of Venice horoscope (image two). Spinola and Oderico were active in Genoa at the same time and knew each other; in fact, they were close enough that Oderico dedicated his Discorsi meteoreologici et astrologici sopra la cometa apparsa nel fine dell’ Anno 1652 (1654) to Spinola. The third name is more of a mystery. Spinola’s name on the title page is pasted down over another inscription, which reads “Ex libris Nicolai Francisci,” who we have not been able to identify.

The notetaker writing underneath Cosimo I’s horoscope, likely Spinola, draws out more about Cosimo I’s life by interpreting other parts of his geniture and cross-referencing to other astrologers. Spinola cites a “Petrus de Silva Hispanus,” who he describes as “an astrologer of illustrious name,” who added information on ascensions and Capricorn in Cosimo I’s horoscope. Spinola also describes Cosimo I’s rise to power following the death of Alessandro de’ Medici in astrological terms: Jupiter’s position when Cosimo I gained power paralleled its position at his birth.

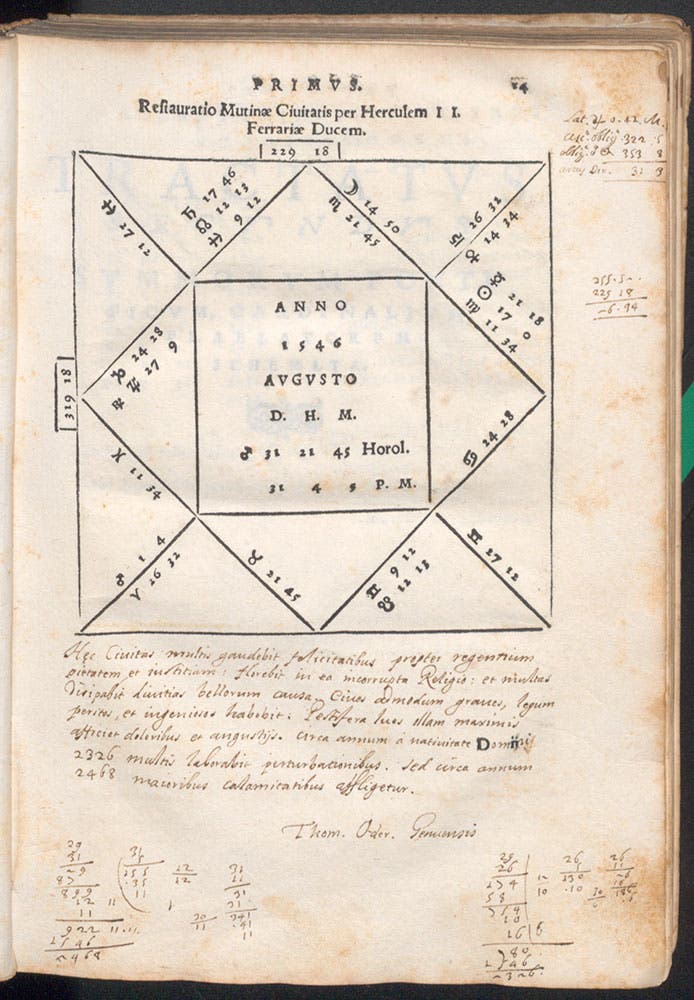

Horoscope for Ferrara, restored in 1546, with annotations by Tomasso Oderico, in Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)

Tomasso Oderico annotated several of the horoscopes and filled the margins with calculations. For example, the horoscope for the city of Ferrara (see above) had no explanatory text, so Oderico added a short biography in which he describes the piety and justice of the rulers, the “uncorrupted religion” that will flourish in it, its use of riches for war, and the effects of a plague. He also predicts disturbances and calamities in the years 2326 and 2468. The arithmetic at the bottom of the page shows how he arrived at 2326 and 2468 via projecting astronomical occurrences hundreds of years into the future. He also handwrote two horoscopes for the years 1656 and 1657, which he inserted into the book (see image one).

Detail of Oderico’s calculations for Ferrara, in Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)

The Library copy of Tractatus astrologicus is a record of astrological happenings in 17th-century Italy, when astrology was quickly losing ground as a science, and a possible artifact in the story of Spinola and Oderico’s working lives and relationship. Each grubby book tells a story. If you own a book, mark it up to your heart’s desire, then lend it to a friend—a librarian or historian may be captivated by it in five hundred years. As for Oderico’s predictions for the city of Ferrara, only time will tell.

For more on Gaurico’s life, times, and work, look to a recent Scientist of the Day post, fittingly published on the occasion of Gaurico’s 549th birthday. Credit is also due to Anthony Grafton’s Cardano’s Cosmos: The Worlds and Works of a Renaissance Astrologer (1999) for information on reading early modern genitures and on Gaurico himself.

![Handwritten astrological computations, in two different pens or hands, on a slip of paper inserted into the Library copy of Tractatus astrologicus, by Luca Gaurico, 1552 (Linda Hall Library)]](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e078e60d-4cde-474e-b4ad-29ee3465860e/Image-1-3364_0057.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)