From Vinegar Baths to Vaccines: American Efforts to Control Yellow Fever

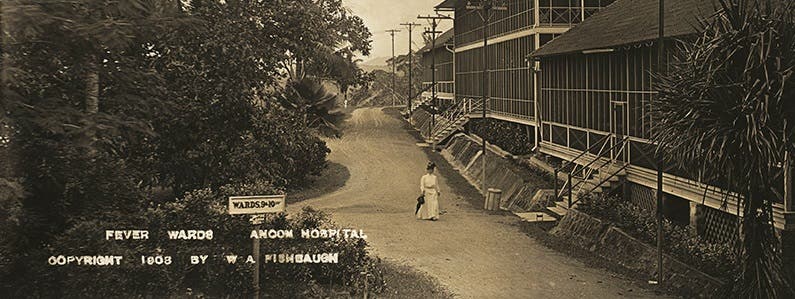

Since arriving in Washington state at the end of January, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has transformed nearly all aspects of American society. These disruptions may seem unprecedented, but history is filled with similar efforts to slow the transmission of viral pathogens, with varying degrees of success. One of the most persistent of these diseases was yellow fever, which wrought havoc on the United States from shortly after independence until the early 20th century. Yellow fever is a vicious disease that first appeared in the Caribbean during the 17th century. Its symptoms range from elevated body temperatures, muscle pain, and nausea to black vomit (due to internal bleeding) and the jaundice that gave the illness its name. Early on, physicians assumed that the disease was caused by vapors emitted from sewage or decaying organic matter. The popularity of this miasma theory explains why physicians in Philadelphia assumed that cases of yellow fever they observed in 1793 could be traced to a shipment of coffee left to rot near the city docks. The 1793 yellow fever outbreak ravaged the capital of the newly independent United States. Less than a month after the first cases were reported in Philadelphia newspapers, the city was burying at least 60 bodies each day. Many people fled to the countryside, and those who remained isolated themselves in their homes to avoid infection. Some embraced preventive measures that seem outlandish today: bathing in vinegar, chewing garlic, or smoking tobacco. Benjamin Rush, a respected doctor and signer of the Declaration of Independence, tried to offer relief to the disease’s victims. His preferred treatment was a combination of purging and bloodletting. Many patients found Rush’s presence comforting, but other physicians criticized him for promoting an unproven cure that could itself be fatal. The arrival of cold weather brought Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic to a close but not before 5,000 people died, approximately 10% of the city’s overall population. Philadelphians built new hospitals and improved the local water system, but the origins of the disease and how it spread remained a mystery. Cities like Memphis and New Orleans continued to suffer from outbreaks. That began to change in 1881, when a Cuban physician named Carlos Finlay proposed an alternative to miasma theory. Noxious gases, he claimed, were not responsible for yellow fever. Instead, the disease was being propagated by mosquitoes, specifically the Aedes egyptii mosquito. Finlay’s his initial efforts to demonstrate that mosquitoes were responsible for spreading yellow fever proved inconclusive. Only after American troops started dying in Cuba during the Spanish-American War did physicians begin to revisit his theories. In 1900, the head of the newly-established U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission, Walter Reed, conducted systematic experiments that confirmed that Aedes egyptii was the vector for yellow fever. Acting on this new information the Chief Sanitary Officer in Havana, William Gorgas, launched a campaign to eliminate mosquito populations and the pools of stagnant water that served as their breeding grounds. Within eight months, the city was free of yellow fever. The successful eradication of yellow fever in Havana led others to adopt similar tactics. The 1905 outbreak in New Orleans would mark the last time that the disease raged unchecked in the United States. Gorgas, meanwhile, was reassigned to Panama, where yellow fever had remained a persistent threat to public health since the French launched their first attempt to dig a canal in the 1880s. He arrived in 1904 and promptly deployed a brigade of 4,000 sanitation workers to fumigate homes and improve drainage systems throughout the Canal Zone. By the end of 1905, yellow fever had been eliminated from Panama and infection rates of malaria, another mosquito-borne disease, had dropped sharply. The construction of the Panama Canal could proceed as planned. Today yellow fever outbreaks still occur in South America and sub-Saharan Africa. Fortunately, Max Theiler, a researcher at the Rockefeller Foundation, was able to synthesize an effective vaccine in 1936. The disease that had once terrorized American cities can now be prevented with a simple injection. Combined with the sanitation measures that Gorgas pioneered in Cuba and Panama, this particular virus has been placed in check for the foreseeable future. Linda Hall Library Resources Online exhibition—The Land Divided, The World United, “Fighting the Fever.” Scientist of the Day—William Gorgas. Linda Hall Library lecture—Dr. Enrique Chaves, “American Medicine and the Panama Canal: Miasmas, Mosquitoes, and Malaria.” Aristides Agramonte, “The Inside History of a Great Medical Discovery,” The Scientific Monthly (Dec. 1915), A.B. Nichols Collection, Linda Hall Library. Other Sources “Outbreak 1793,” The Pulse [!public!], Mar. 4, 2020. “The Mysterious Malady: Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Aug. 28, 2019. U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission—Online exhibition curated by Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia. The Panama Canal: A Triumph of American Medicine—Online exhibition curated by the Clendening History of Medicine Library.