Scientist of the Day - Achilles Pirmin Gasser

Achilles Pirmin Gasser, a physician, historian, astrologer, and cosmographer was born on November 3rd, 1505, on the island town of Lindau on the Bodensee, located along the southern border of modern Germany. Political dignitaries including Holy Roman Emperor Charles V consulted him for medical advice, and he exchanged books and correspondence with scholarly luminaries like Andreas Vesalius, Conrad Gessner, and Sebastian Münster, but today he is best remembered for his place among the early promoters of Nicolaus Copernicus’s theory that the Earth revolves around the Sun rather than resting at the center of the cosmos.

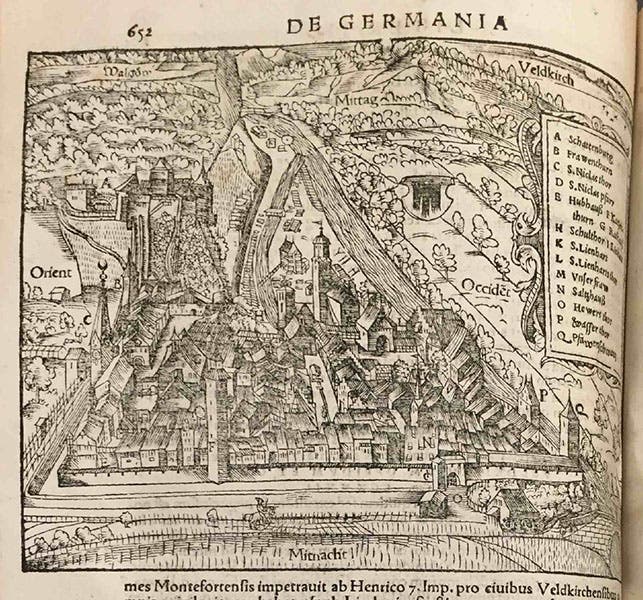

Gasser began university studies at Wittenberg in 1522, only five years after Martin Luther had affixed his famous 95 theses to the door of the All Saints’ Church. During his time there, he purchased a set of astronomical tables by Regiomontanus and additional books on mathematics, signaling both the early stages of his life-long interest in the celestial sciences and the means by which future historians would track his career using the meticulous acquisition notes he made within volumes of his burgeoning library. After three years at Wittenberg, he continued with peripatetic medical studies in Vienna, Montpellier, Avignon, and Orange, before returning to the Bodensee area to become a city physician in Lindau and then farther south in Feldkirch (second image, below).

One of Gasser’s predecessors as city physician in Feldkirch had been beheaded in 1528 for swindling and stealing from his patients, which would seem an inauspicious sign for the position. Nevertheless, the outcome of this judicial proceeding would indirectly contribute to Gasser’s subsequent fame, as he became a scholarly mentor and then colleague for his predecessor’s son. The young Georg Iserin lost the right to use his executed father’s name, but he subsequently adopted a sobriquet based on the ancient Roman province where Feldkirch was located, and as Georg Rheticus he followed in Gasser’s footsteps to Wittenberg’s university in 1532.

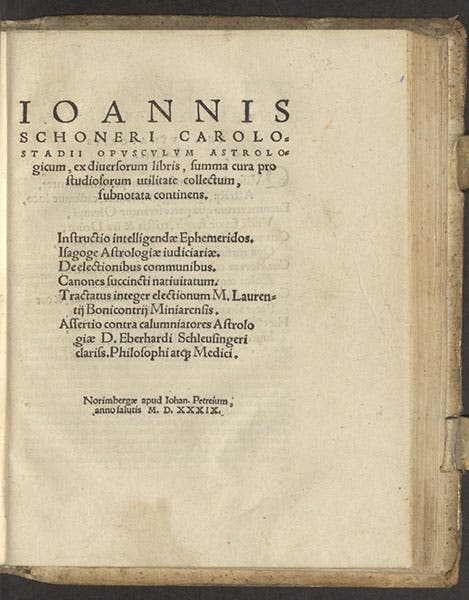

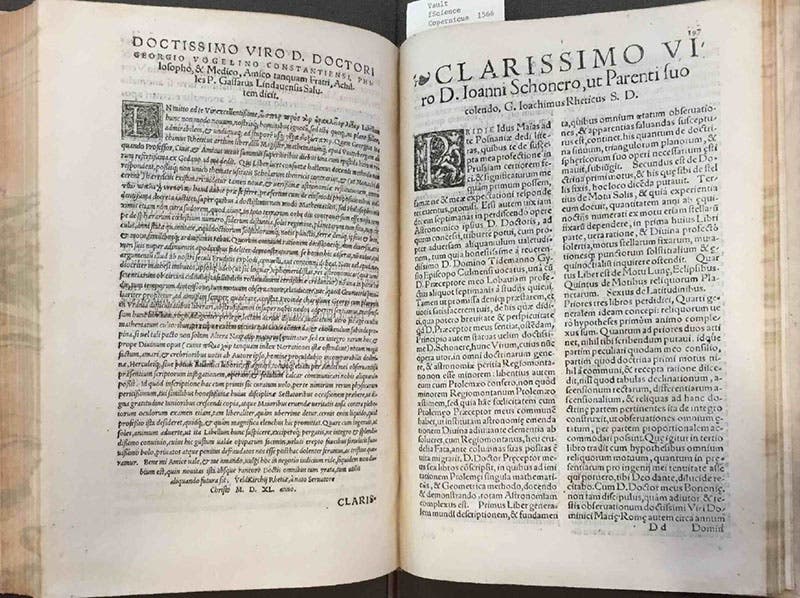

When Rheticus, now a professor of mathematics at Wittenberg, returned to Feldkirch to visit Gasser almost seven years later, he brought and inscribed several books as gifts. The library owns copies of two of these volumes, a Greek and Latin edition of Ptolemy’s astrological writings and another astrological work by Johannes Schöner (third image, below).

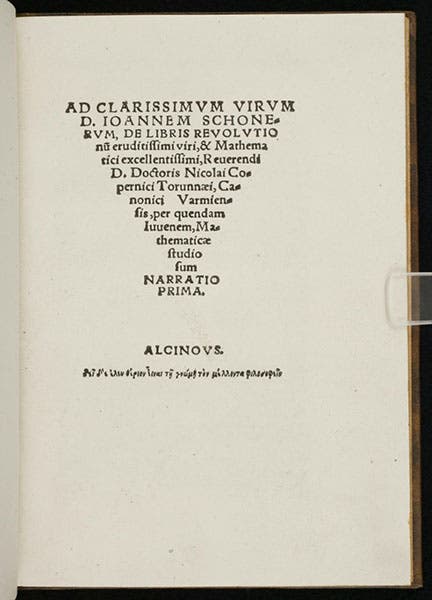

Both of these works had been published by Nuremberg’s foremost printer Johannes Petreius, but Petreius’s most renowned publishing score would come from the next stop on Rheticus’s journeys, because after leaving Feldkirch, Rheticus headed north to his famous meeting with Copernicus in the Baltic coastal town of Frombork. Once again, he arrived bearing a stack of gift books from Petreius, and after a few months spent studying Copernicus’s work and persuading the now elderly scholar to finish writing his book, Rheticus dashed off a short Narratio prima (or “First Account”) of the Copernican theory, had it printed in Gdansk in 1540 (fourth image, below), and promptly sent a copy back to Gasser.

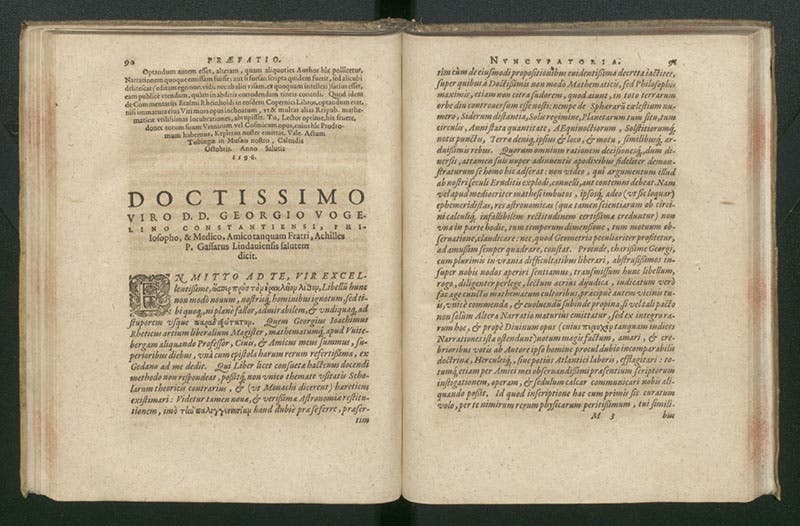

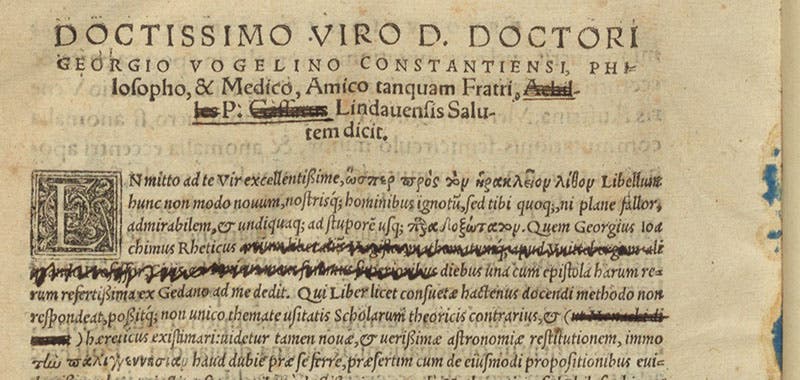

Gasser’s enthusiasm for this work was such that he not only liberally annotated the copy Rheticus had sent him but quickly arranged for a second edition to be printed in Basel, and this is where the story of Gasser in the Linda Hall Library collections gets particularly interesting. The 1541 edition of the Narratio prima included a preface by Gasser, and when the Basel printer Heinrich Petri decided to reprint Copernicus’s own work in 1566 – the first edition by Petreius had appeared in 1543 – he decided to include Rheticus’s shorter account as an appendix, including the preface by Gasser. Below we see what Gasser’s preface and the first page of Rheticus’s account look like in a pristine copy of the second edition of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus.

Gasser’s uncensored preface to Rheticus’s Narratio prima in the second edition of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus, 1566 (Chapin Library, Williams College)

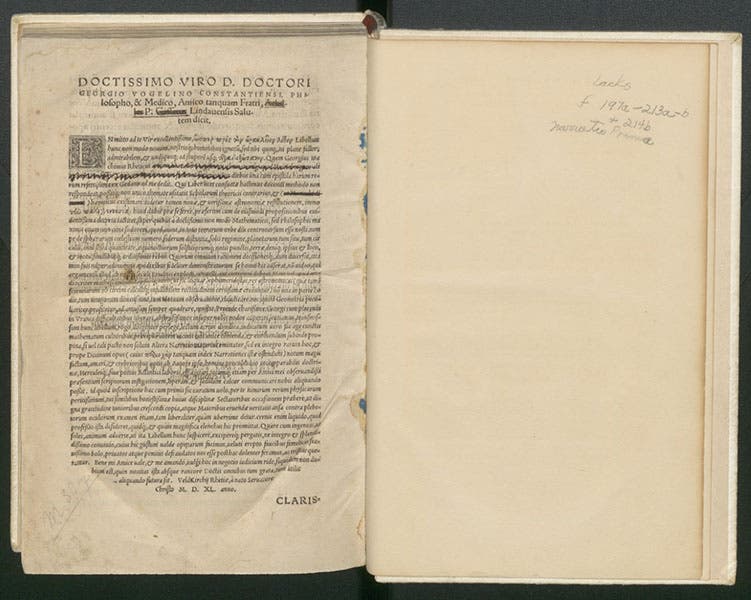

The Linda Hall Library’s copy of this volume, by contrast, bears witness to the early impact of church censorship decrees. Copernicus’s work was not targeted by the Index of Prohibited Books until 1616, and even then it was only “suspended until corrected,” with a series of relatively minor edits issued several years later that faithful readers were supposed to apply to their copies. Prior to that time, however, there were numerous other decrees that targeted both texts, especially on religious subjects, and authors, especially if they were Protestants. One of these earlier decrees specified that Rheticus’s Narratio prima should be excised from copies of Copernicus’s work, and we see in the library’s copy that this is exactly what has happened (sixth image, below). Gasser’s preface could not be cut out because it was printed on the reverse side of the final page of Copernicus’s text, but the entire main text of the Narratio prima is missing.

Censored copy of Gasser’s preface, showing the rest of Rheticus’s text completely excised (Linda Hall Library)

Looking more closely at Gasser’s preface, we see that it has likewise not been left undisturbed (seventh image, below). Gasser’s name, as a famously Protestant physician, has been crossed out in the heading. Interestingly, Rheticus’s name four lines down in the preface has been left alone, but the description of his position as a professor at Luther’s Wittenberg university has been scribbled over. Finally and somewhat comically, in the sentence two lines farther down where Gasser remarks that Copernicus’s theory might be considered “opposed to the common theories of the schools and, as monks would say, heretical,” the phrase “as monks would say” has been emphatically crossed out so that the statement more simply notes that Copernicus’s theory might be considered heretical.

Closeup view of the censorship of Gasser’s preface (Linda Hall Library)

Beyond these censorship markings, there is another remarkably interesting feature of this volume that was recently spotted by Dr. Jamie Cumby, the library’s Assistant Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts. If you closely examine the right-hand side of the page with Gasser’s preface, there are fragments of blue paper stuck with paste along the gutter. These are remnants of a characteristic type of paper that booksellers of this era used as temporary wrappers when providing texts to customers, who could then add their own more customized bindings. In this case, the bookseller seems to have provided a copy of Copernicus’s work that was pre-prepared to match the Index decree requiring removal of the Narratio prima, but an excess of enthusiasm in applying paste to the spine of the text left a few remnants of the temporary wrapper after it was moved into its current binding. You can hear more about this and other examples of censored volumes in the library’s collections in the recent recorded lecture on banned books by Dr. Cumby and Professor Hannah Marcus.

Despite lacking a clean copy of Gasser’s preface in this edition of Copernicus, the library does hold two additional examples of his text. When Johannes Kepler published a defense and interpretation of the Copernican theory forty years later, his former teacher Michael Maestlin added another reprint of the Narratio prima with Gasser’s preface at the back of the book. The library owns both the 1596 first edition of Kepler’s Mysterium cosmographicum (final image, below) and the second edition from 1621.

Gasser received a first edition of Copernicus’s work from Petreius, and as in the case of Copernicus, the gift books from Petreius and Rheticus seem to have helped recruit him to publish in Nuremberg. He sent Petreius several astrological prognostications and a treatise on plague for printing, but his reputation as a physician and earlier publications on history and the comets of the 1530s also ensured that the bright lights of the imperial city of Augsburg would soon beckon him northward. The Augsburg council granted him tax-free residence in 1546, and he would remain there until his death in 1577. His best-known publication from these later years was probably his edition of Petrus Peregrinus’s medieval essay on the magnet, but he also contributed several city histories, including the view of Feldkirch shown above, to Münster’s massive Cosmographia project.

The only known contemporary portrait of Gasser is a hand-drawn sketch from 1571 (first image). His legacy lives on, however, in his personal library that numbered nearly 3000 volumes by the time of his death. It eventually became part of the enormous Palatinate collections in Heidelberg, which were captured and sent to Rome as loot during the Thirty Years War. Thus, the Wittenberg alumnus whose name was a target of early Catholic censorship now somewhat ironically has many of his books preserved within one of the most valuable collections in the Vatican library.

Karl Galle (karlgalle@aucegypt.edu) is a former fellow at the Linda Hall Library and is currently working on a biography of Nicholas Copernicus.