Scientist of the Day - Adolphus W. Greely

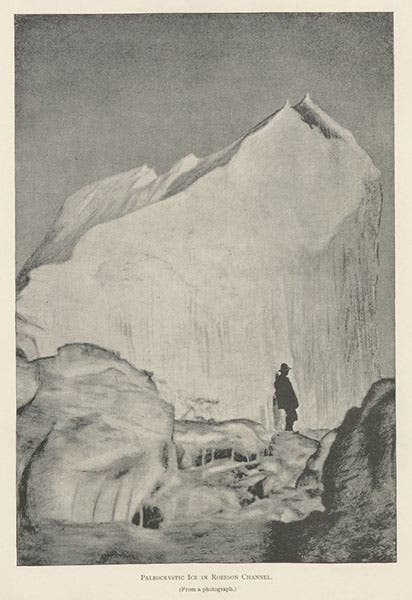

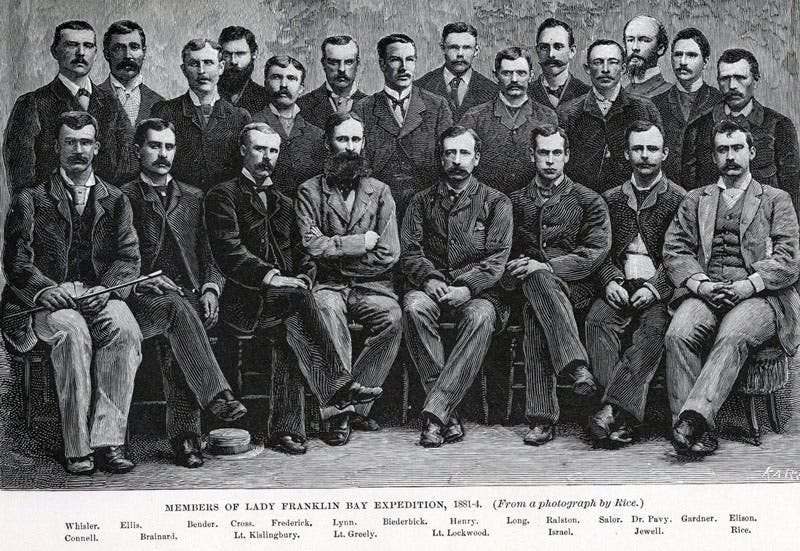

Adolphus Washington Greely, an American Army officer, died Oct. 20, 1935, at age 91. In 1881, Greely (who went by the name A.W. Greely) was appointed to lead an expedition, sponsored by the U.S. Army Signal Corps, to Lady Franklin Bay, which is way up the small channel between Greenland and Canada's Ellesmere Island, far above the Arctic Circle. Supposedly, the purpose of the “Lady Franklin Bay Expedition” was to participate in an International Polar Year and to do scientific research; in reality, the secret goal seems to have been to get closer to the North Pole than a team sent out by the Nares expedition in 1876, which held the current "Furthest North" record. Greely's crew of 21 men were ferried to Lady Franklin Bay by a steamer, Proteus (third image), picking up two Greenlanders and two other crewmen on the way, including a physician, swelling the crew size to 25. The group photograph was taken before the Proteus left; the doctor’s image had to be pasted in later, to the right in the back row (second image)

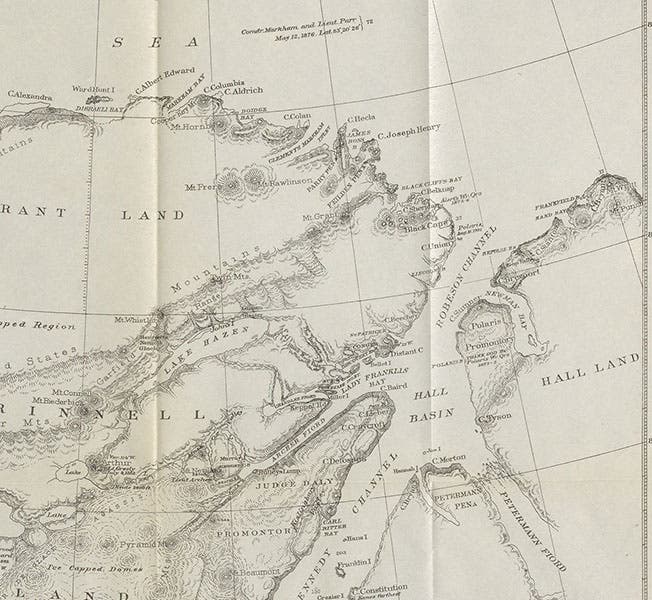

The men built a large hut, Camp Conger, on the north side of Lady Franklin Bay (see map, fifth image), and the Proteus returned home. The plan was to send a ship in the summer of 1882 to resupply the expedition, and another in 1883. Meanwhile, small parties went up to explore Grinnell Land (the northern tip of Ellesmere Island) and crossed the Nares Strait to Greenland to explore and map its northern coast. One team did in fact reach 83° 24’ N, which beat the old Furthest North record by 5 miles.

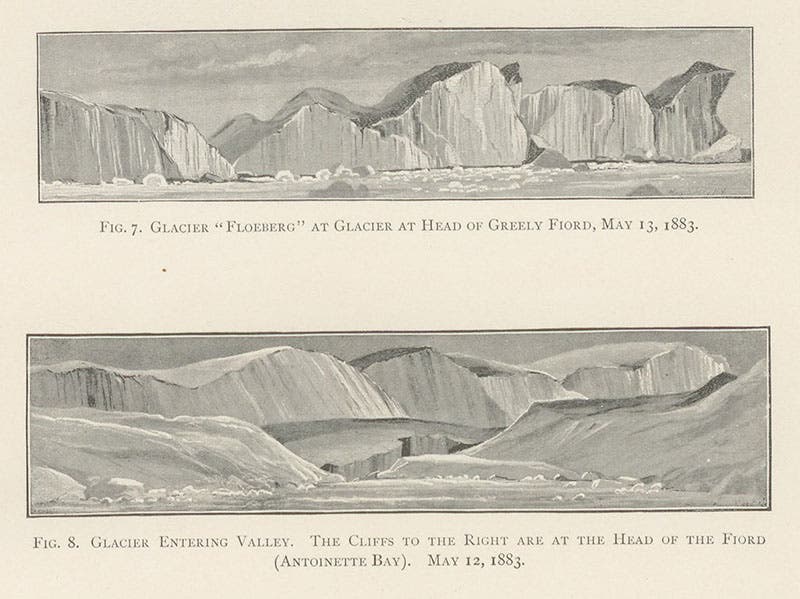

One of the novelties of the Greely expedition was that it took along a photographer, George W. Rice, who was a civilian (and a Canadian), given the rank of sergeant for the military occasion (he is front row, far right, in the group photograph). The Nares expedition had also had a photographer (see our post on Nares), but it was by no means commonplace yet to replace the ship's artist with a camera. Greely published a two-volume narrative of the expedition in 1888, called Report on the Proceedings of the United States Expedition to Lady Franklin Bay, Grinnell Land, and he included many of Rice's photos in his report, converted somehow to engravings, some of which we show here. We have two copies of Volume 1 of the Report in the Library, which is not quite the same as having one copy of volumes 1 and 2; so there are undoubtedly some Rice photographs in volume 2 that I have not seen. The ones included here are all from volume 1.

Unfortunately, the Greely expedition unraveled. Greely and the physician, Dr. Pavy, couldn't stand each other, and Greely could not get rid of him, because a doctor was an essential element on an expedition like this. Then the first supply ship ran into a solid icepack and could not get through in the summer of 1882. The Proteus herself was sent in 1883, and it not only failed to reach Lady Franklin Bay, it was crushed by the ice and sank. The crew ran out of food and could not reprovision itself, since game was scarce, especially through the winters. Greely tried to lead the crew south overland at the end of 1883, hoping to find a spot where a whaler might pick them up, but the men were too weak, and they got no further than Pim Island, in the Nares Strait, where they began to die off, one by one, of starvation and scurvy.

Detail of map of Grinnell Land, with Lady Franklin Bay at center and Camp Conger just above it; Greenland is on the right, Ellesmere Island on the left; in Report on the Proceedings of the United States Expedition to Lady Franklin Bay, Grinnell Land, by A.W. Greely, vol. 1, 1888 (Linda Hall Library)

In the spring of 1884, a ship was sent by the U.S. government to find and rescue the crew, but when they arrived in June of 1884, only 7 men remained alive, just barely, including Greely, and one of those 7 died on the return home. When the crew and Greely finally arrived in New York City, they were hailed as heroes, until it was discovered that one of the dead men had been executed (for stealing food), and that there was some evidence from the buried bodies on Pim Island of cannibalism, which Greely fiercely denied knowing anything about. In the end, the only solid achievement of the Greely expedition was to get five miles further north than the Nares expedition, which hardly seemed to justify the deaths of 19 men, including Rice the photographer and Pavy the physician.

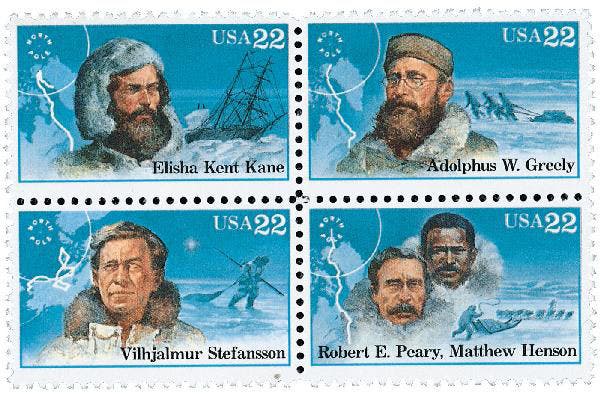

Time is kind to some failures, and before long Greely was being remembered as an intrepid Arctic explorer, one of the few Americans included in such ranks. When the U.S. Postal Service issued a set of four stamps in 1986 to honor American explorers of the Arctic, they included Greely, whose stamp is at upper right in the block of four we show (sixth image), and uses a good photo portrait of Greely, which I could not otherwise find in a copyright-free state. The USPS also included a stamp honoring Robert Peary and his African American crew member Matthew Henson, which would be laudable, had Peary and Henson reached the North Pole, as Peary claimed, but which now turns out to be very unlikely.

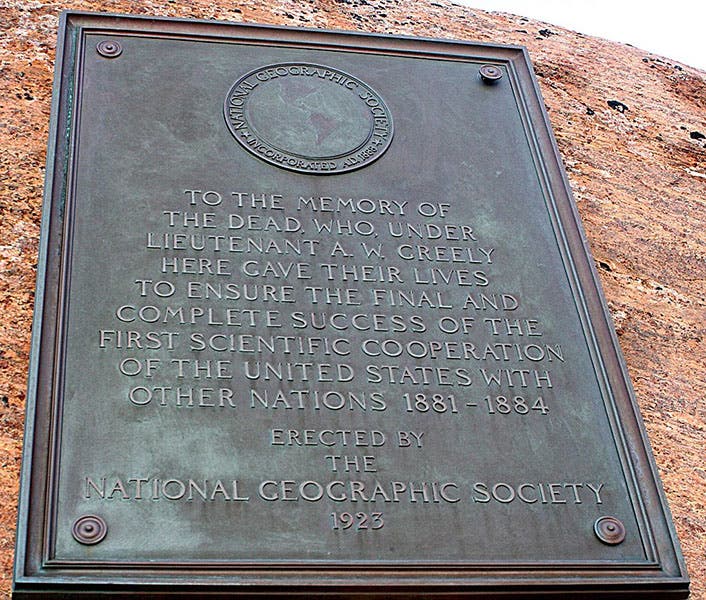

A better memorial was one for the 19 members of the Greely expedition who died in the Arctic. This bronze plaque was put in place on Pim Island in 1923, sponsored by the National Geographic Society (seventh image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.