Scientist of the Day - Albert C. Koch

Albert C. Koch, a German/American naturalist, showman, and entrepreneur, was born May 10, 1804, near Leipzig, Germany. He came to the United States in 1827 and set about making his mark in his new country. He settled in Saint Louis, and in 1836, he opened the Saint Louis Museum on the waterfront, right about where the Gateway Arch stands today. He displayed both natural and cultural artifacts in the museum, including much of the collection of William Clark of Lewis-and-Clark fame, which Koch somehow acquired after Clark's death in 1838.

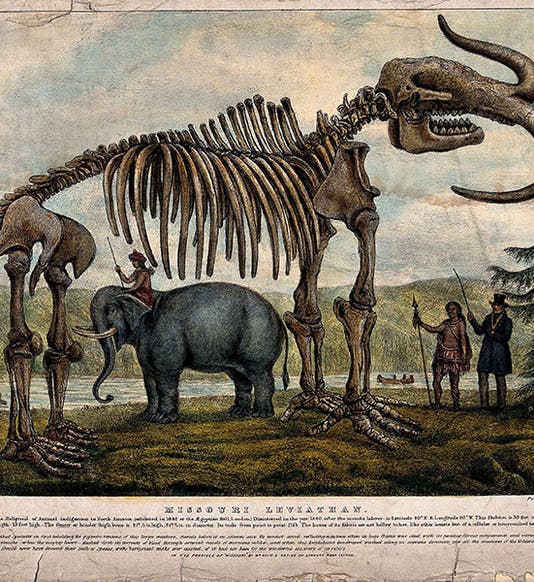

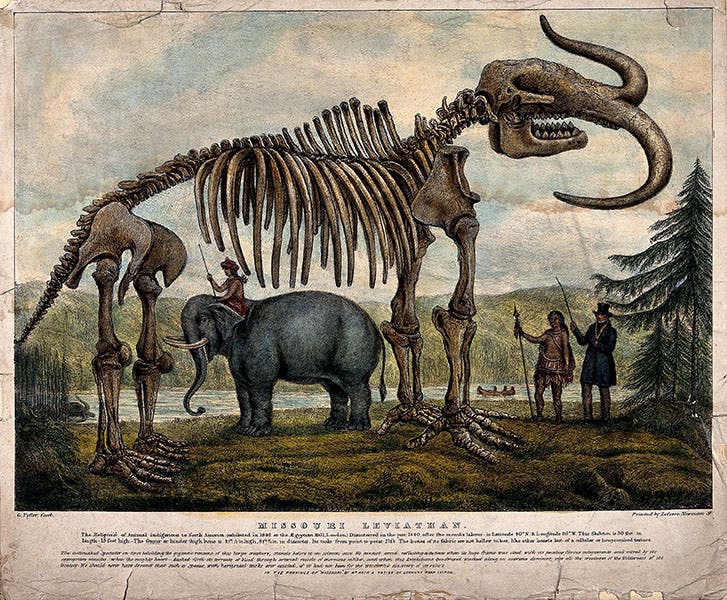

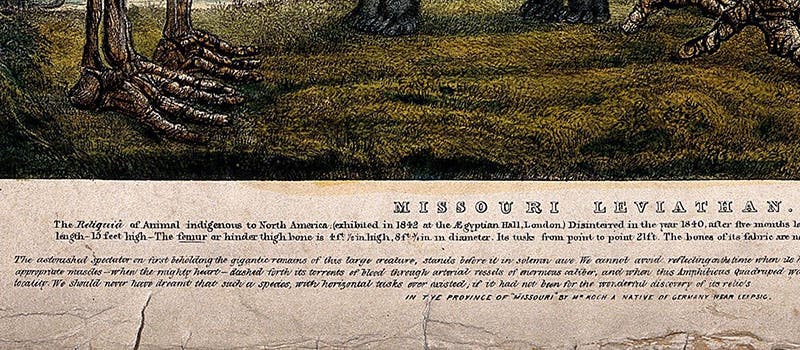

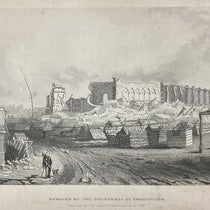

Koch’s great leap forward came in 1840, when he mounted in his museum a skeleton of an animal that he called the Missourium, or more commonly, the Missouri Leviathan. He had found what we now know to be mastodon bones in various locales around Saint Louis, but the big find came in Benton County on the Pomme de Terre River, quite a ways from Saint Louis, in the Ozarks. He claimed to have found the complete fossil skeleton of an unknown behemoth, one that made the mastodon seem puny by comparison. According to his figures, the monster was 15 feet tall and 32 feet long. Its tusks did not curve up or down, but outward - Koch said he was certain of this because he found one of the tusks in place. A lithograph was later made according to Koch's description, showing the Missourium about twice as large as the actual mount, with the poor mastodon cowering beneath the bones of his giant relative (first image).

When the Saint Louis community did not come out in droves to view his specimen (and make him rich), Koch closed the museum and took the Leviathan on tour to Europe, where it was a big hit, especially in London, where it attracted the attention of the reigning comparative anatomist, Richard Owen. It was after this continental tour that the lithograph shown in our first image was printed.

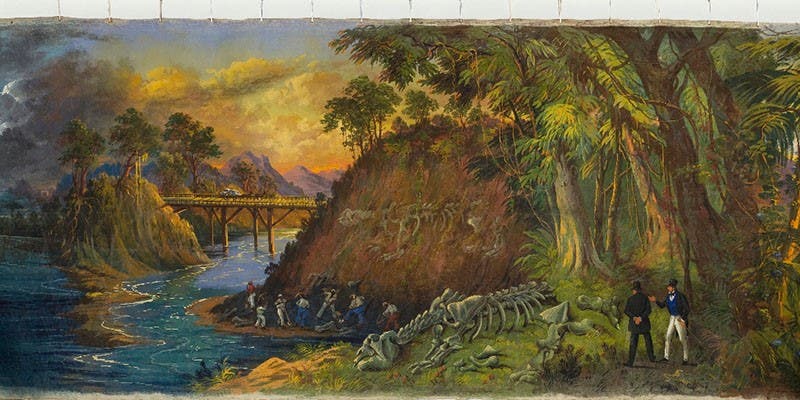

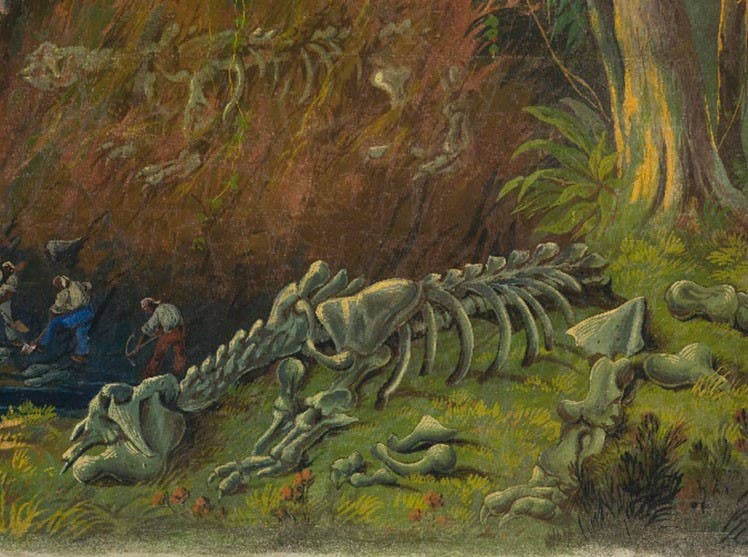

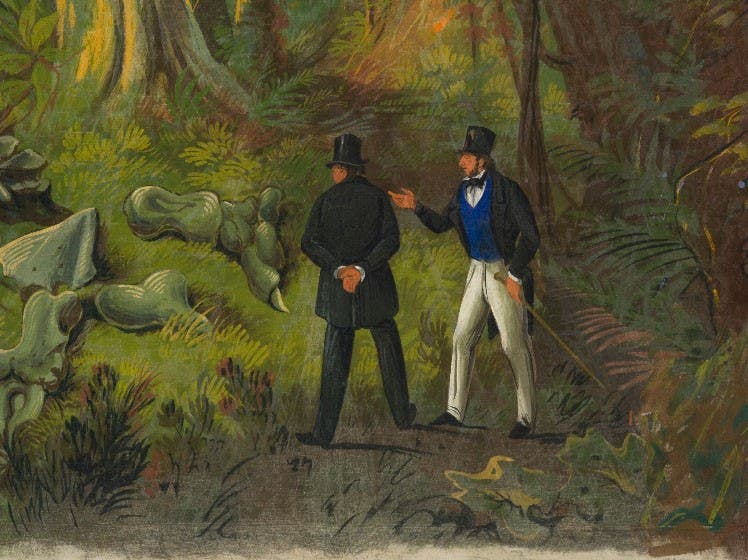

In 1850, the Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley opened in Saint Louis, painted by John L. Egan on commission from Montroville W. Dickeson. This 348-foot painting consists of 25 panels, one of which depicts the finding of the Missouri Leviathan along the Pomme de Terre River in 1840. This panorama still survives, amazingly, and has recently been restored by the Saint Louis Art Museum, where it is on display. We reproduce here a photograph of the entire Leviathan panel (third image, just above).

We also show several details of the Leviathan panel; one depicts a Leviathan skeleton on the bank of the river; a second shows Koch himself, in the white trousers, and Dickeson, who narrated the presentation of the slowly scrolling panorama to the audience (fourth and fifth images above). Koch must not have been available for consultation by Evans, for the skeleton dug up is surely not that of any mastodon relative, but looks much more like a megatherium, as you can see by comparison with the specimen depicted in our post on Juan Battista Bru de Ramon.

The Missourium, along with many other fossil bones from Koch's collections, was acquired by Owen in 1844 for the newly formed Natural History division of the British Museum. Owen, who was considerably better than Koch at restoring fossil skeletons, recognized that that Missouri Leviathan was made up of the remains of several mastodons, with added vertebrae and extra bones that exaggerated its size. He had it taken apart and reconstructed, with the tusks properly realigned, and the result was a regular mastodon, but nevertheless a splendid one. It is still on display in the Natural History Museum in London (sixth image, above). I have not seen it – I hope that its back-story is recounted somewhere nearby.

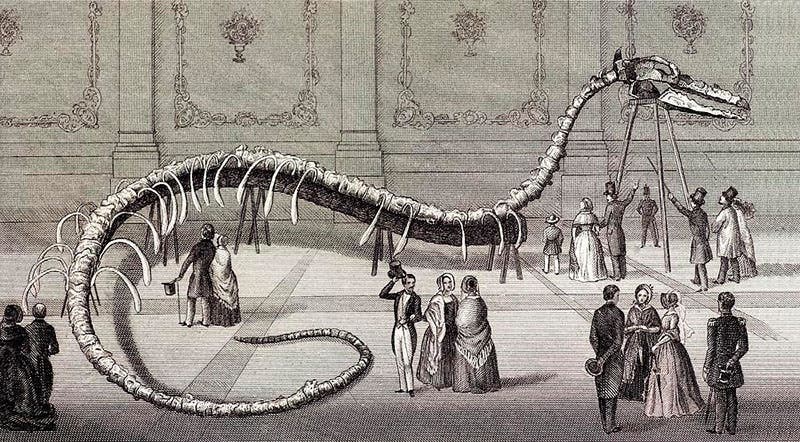

Koch returned to Saint Louis and continued to search for fossils that he could mount and take on the road. He found some giant snake-like skeletons in Alabama, and fashioned from them a mount that he called Hydrarchos, which looked like an incredibly long sea serpent with a massive skull (seventh image, above). It was so long because Koch fashioned it from at least two specimens of what we now call Basilosaurus, an early (and lengthy) whale. Koch took it on tour, and it was purchased in 1848 by a museum in Prussia, where, like the Missourium, it was later taken apart and properly reconstructed.

Koch eventually moved to Illinois to live with his brother, and he died there in 1867. His tombstone (eighth image), in a cemetery in Golcanda, Illinois, praises, in Latin, Koch’s skill at raising “Titans from the grave,” which now “stand as his true monuments.”

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.