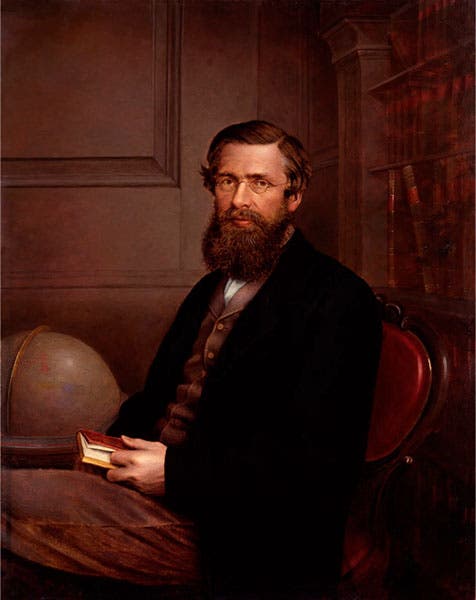

Scientist of the Day - Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace, an English naturalist, was born Jan. 8, 1823, in Wales. Wallace is well-known as a co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, and for making Charles Darwin realize that he needed to stop researching and write his Origin of Species before others beat him to the punch. We told the story of his interactions with Darwin in a post just over a year ago. In a much earlier post, we briefly discussed his life as a naturalist; today’s post is an expansion on that.

Wallace, unlike Darwin, came from a lower middle-class family, and had to earn his way as a young man, so his formal education ended at the age of 14, and he never attended a university. Like and with his older brother, he worked for some years as a surveyor, both in Hertford, where he grew up, and in London. He learned to like the outdoors, and began collecting naturalia, especially beetles (just like Darwin). He read and was impressed by The Vestiges of Creation, an anonymous book of 1844 (now known to have been written by Robert Chambers) that proposed a Lamarckian mode of evolution. He also admired Darwin’s narrative of the voyage of the Beagle, which probably planted the seeds for Wallace’s own subsequent travels.

In 1843, he met Henry Walter Bates, who was of similar social status as Wallace and shared a wish to explore the world. In 1848, the two set off for the Amazon basin to collect specimens to sell to London vendors of exotica, especially a broker named Samuel Stevens. They were quite successful, but in 1852, Wallace decided to return home (Bates stayed on for 7 more years), and the ship carrying Wallace and all his specimens and notes burned to the waterline in mid-Atlantic. Wallace survived, but few of his specimens did. His collections had been insured by Stevens, so the loss was not financial but scientific. Wallace decided to try again.

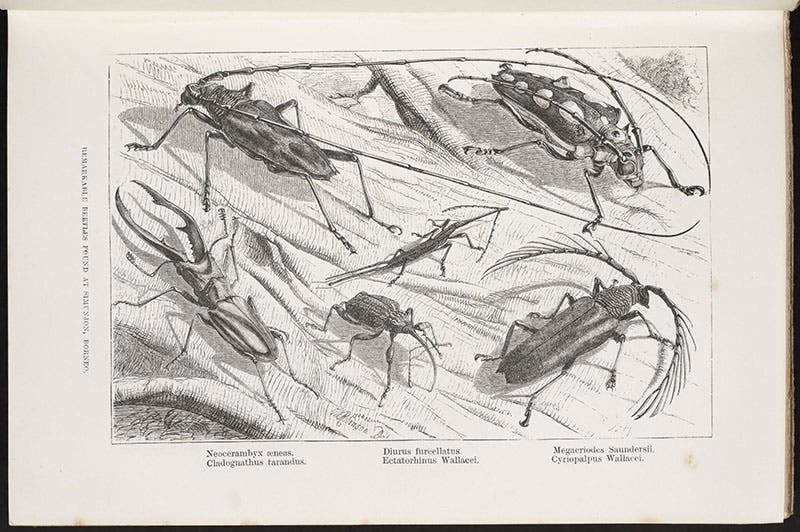

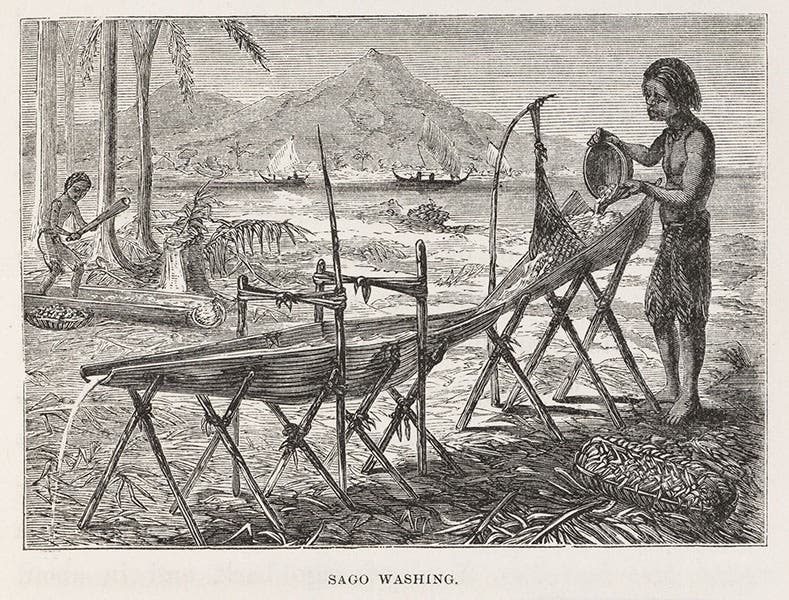

This time, he chose the East Indies, what was called then the Malay Archipelago. He booked passage on a commercial ship, with the financial backing of Stevens and the help of a patron in Sarawak. Over the course of 8 years, he visited Singapore, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Lombok, Malacca, and other islands, paying locals to bring him specimens, especially insects. Living conditions were difficult, and he often had to delay passage to new destinations because he had no money. But he managed to collect some 125,000 specimens, which were shipped back at regular intervals on commercial steamships to Stevens, with instructions on what to sell and what to keep. It was while on the island of Ternate that he wrote his famous letter to Darwin that scared Darwin to death and set him down to write the Origin, and which we discussed in our last post on Wallace.

One of the important discoveries that Wallace made in his collecting travels was that the islands east of Bali have a completely different population of animals than those on Lombok and to the east, even though nothing separates them but a few miles of ocean. He would propose the existence of two faunal populations, separated by a line later known as Wallace’s line. This would be a significant step in understanding the relevance of evolution to biogeography, a science in which Wallace was a major player.

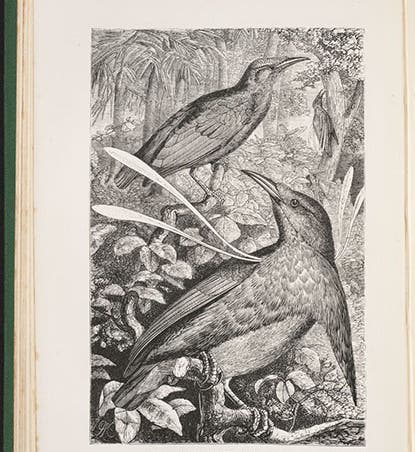

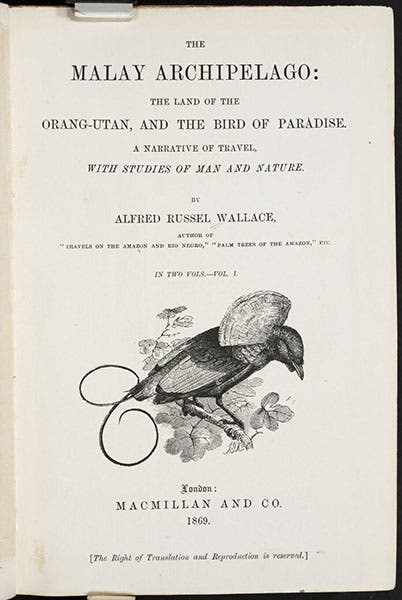

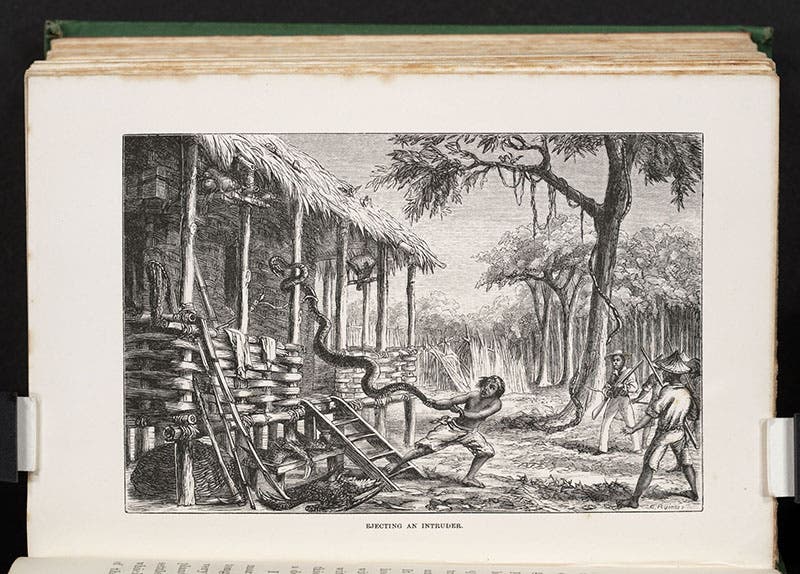

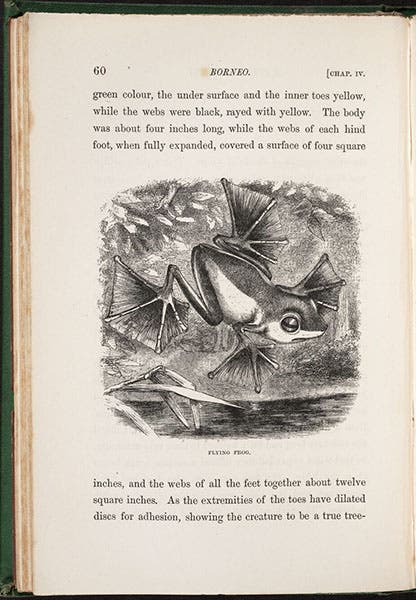

After he returned to England in 1862, Wallace sorted and studied his collections, wrote and published a number of scientific papers, entered scientific society, and began writing a book on his adventures in the East Indies. The book was published in 1869 as The Malay Archipelago, in two volumes. It is similar in style and scope to Darwin’s narrative of the voyage of the Beagle, and is even more readable (in my opinion), and much better illustrated than Darwin’s book. I am not sure how Wallace was hooked up with his illustrators, but they were the best in the business, and included Joseph Wolf, T.W. Wood, Thomas Baines, E.W. Robinson, and J.G. Keulemans, on several of which he have written profiles. The result is a work that is visually very appealing, as well as exotic. Our post today is illustrated with wood engravings from our library’s copy of The Malay Archipelago. You may see others in our first post on Wallace.

If you decide to read The Malay Archipelago, I highly recommend a companion book, Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago (2013), edited by John van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker, which contains all the surviving letters written to and from Wallace while he was in Indonesia, and provides a different and welcome slant on his travels and discoveries.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.