Scientist of the Day - Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush, an American physician, was born Jan. 4, 1746, in Byberry, then 10 miles outside Philadelphia (and now within the city). He attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), was apprenticed to a physician, studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and returned to Philadelphia in 1769 to set up a practice and teach at the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania).

Rush was a paradoxical man. He was by all accounts the leading citizen of Philadelphia at the turn of the 18th century and by far the most famous and well-respected physician in the early Republic. At one point, fully 3/4 of all the physicians in the United States had studied under Rush at the medical school of the College of Philadelphia, which is a staggering figure, and when you add to that the fact that Rush was an ardent and outspoken patriot, and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, you can see the makings of quite a legacy. No less a figure than John Adams said of Rush, upon his death: "in the estimation of unprejudiced philosophy, he has done more good in this world than Franklin or Washington”.

Yet Rush’s medical views and practices were idiosyncratic and antiquated, even by the standards of the day. He came to believe that illness was caused by chemical and physical imbalances in the body, and that the best treatment for any disease was to prescribe massive doses of purgatives and blood-letting. "Purge and bleed! Purge and bleed!" was the epithet often applied derisively to Rushonian medicine by opponents. In 1860, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a devastating critique of Rush's medical teachings, which he saw as a reflection of the climate of revolution in America, where everything had to be heroic and bigger than life; "What wonder that the stars and stripes wave over doses of ninety grains of sulphate of quinine, and that the American eagle screams with delight to see three drams of calomel given at a single mouthful."

Rush was at his best and worst during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. Bear in mind that no one knew that the disease is caused by a virus and that the principal vector is a mosquito. Nor could yellow fever be easily distinguished from other diseases in its early stages. But Rush did the best he could to halt the epidemic. He remained in the city throughout and worked tirelessly, seeing hundreds of patients every day. Many of his sickest patients recovered under his care. Yet one would be hard-pressed to find anything in his treatment of purges and cupping that hastened any recoveries. Such was the state of medicine before the advent of the germ theory of disease in the later 19th century. It is hard to be critical of anyone in Rush’s day except the uncaring or the profit-minded. And Rush was neither of those.

Rush wrote an autobiography, starting it in 1800, comprising 10 notebooks, 8 of which survive in the Library Company of Philadelphia. His “Travels through Life” is particularly enlightening about the revolutionary war years, when Rush was in effect the Surgeon General of Washington’s army. He took Washington and other officers severely to task for the abysmal state of the army hospitals, which he claimed were killing more soldiers than the enemy. He also devoted a section of a notebook to an evaluation of each of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Most do not garner high praise, but two exceptions are John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, whom he praised as the true fathers of the young republic. He seemed to have esteemed Adams even more than Jefferson. Later, when Adams and Jefferson had fallen out and were no longer speaking, Rush was instrumental in 1811 in writing a letter to Jefferson that brought the two men back together and restored their friendship.

In his later career, Rush was a strong advocate for better treatment of the mentally ill, who at the time were simply locked up in insane asylums, with no one making any effort to understand the source of their illness. Rush even wrote and published a book on diseases of the mind, which might be his finest contribution to the medical arts. We do not have this work, or any of Rush’s books, in our library, as medicine is out of scope for our collections. But we do have several printed versions of his autobiography.

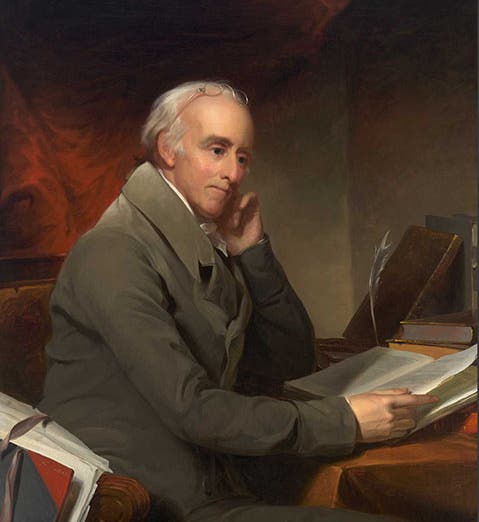

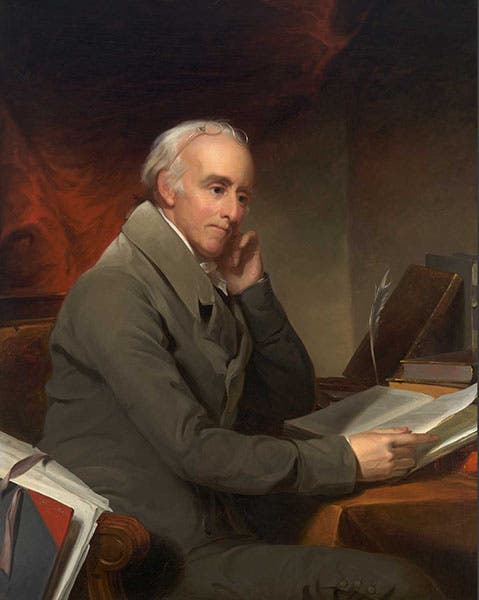

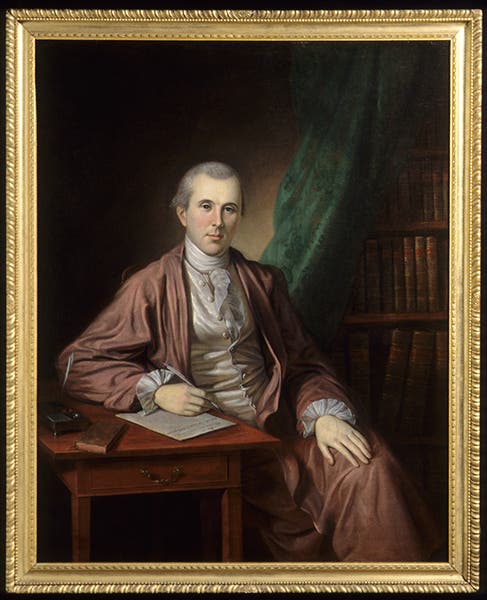

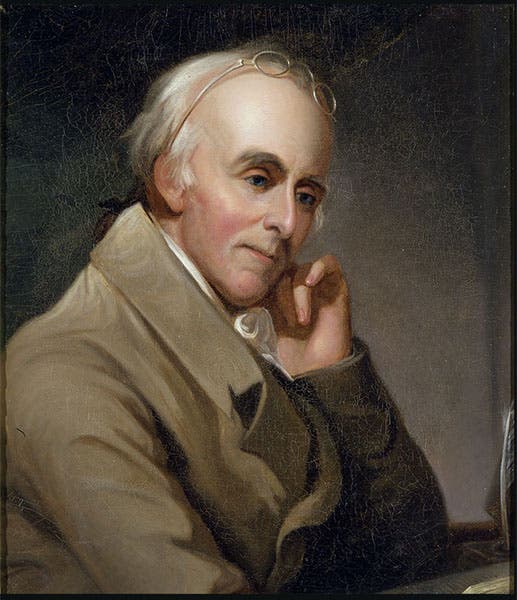

There are three notable portraits of Rush, although the third is based on the second. Charles Willson Peale painted Rush’s likeness in 1783, when he was something of a war hero (second image). This painting is in the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. Thomas Sully painted a second portrait almost 30 years later, which shows a much more thoughtful Rush (first image). That painting is in the Trout Gallery of Dickinson College, of which Rush was a principal founder (first image). In 1818, Charles Willson Peale copied the central area – head and shoulders – of Sully’s portrait, giving it his own unique stamp (third image); this portrait is in Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia.

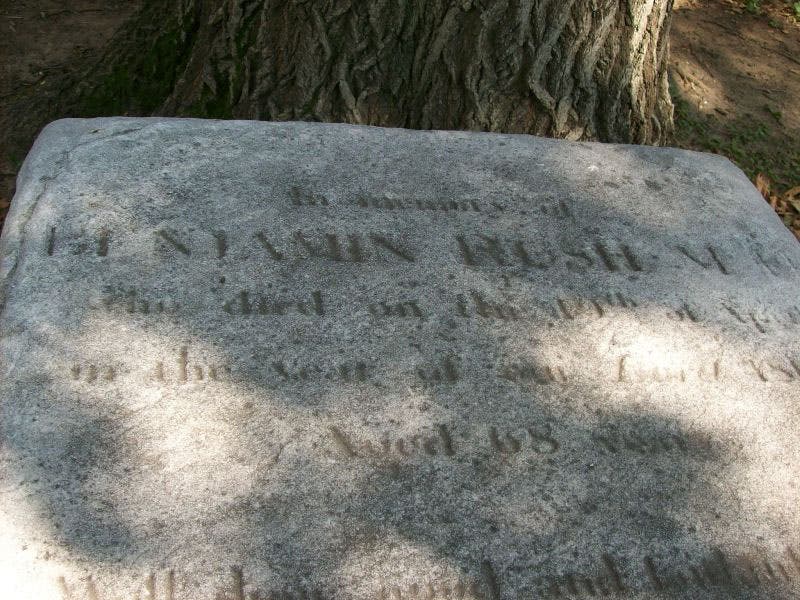

Rush died in 1813, shortly after Sully painted his portrait, and he was buried in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, not too far from the tomb of Benjamin Franklin (fourth image). His grave was refurbished not long ago by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, who added a bronze plaque (not visible here) on the side of his headstone (fifth image). In 1965, the American Psychiatry Association had added their own plaque, on which Rush was not only praised for his medical career and his Revolutionary War activities, but also hailed as the “‘Father of American Psychiatry,” which would no doubt have surprised Rush, and probably pleased him as well (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.