Scientist of the Day - Bernardino Telesio

Bernardino Telesio, an Italian natural philosopher, died Oct. 2, 1588, at the age of 78. Telesio was born in Cosenza in Calabria, down on the boot of Italy, which at the time was part of the Kingdom of Naples, a key state in the Spanish Empire. Natural philosophers who hailed from Naples tended, like their pizza, to be different from that of Florence, more willing to raise philosophical trouble than the gentle humanists of Tuscany. Giordano Bruno was from Naples, and he ran seriously afoul of the Inquisition in Rome, as did the slightly later philosopher, Tommaso Campanella, who spent 29 years in prison, thanks to religious authorities. Telesio was spared imprisonment, although as soon as he died, all of his works were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books "until corrected." When asked by his heirs to make those corrections, the Congregation of the Index replied that any attempt at correction was hopeless. Telesio, Bruno, and Campanella are considered to be the three greatest natural philosophers of southern Italian heritage in the late Renaissance. Giovanni Battista della Porta of Naples is always left off this list, as if he were not a philosopher, and perhaps he wasn’t, but for this occasion, I include him in what is now a list of the four great natural philosophers of southern Italy.

Telesio's only sin, really, was in trying to do natural philosophy without Aristotle. Aristotle thought too much, according to Telesio – he tried to use reason to figure out what the world is made of and how it works, so his physics turned into metaphysics. What we need to do, said Telesio, is let nature tell us all about herself, and if we wish to learn what she has to say, we need to use our senses, not reason. In advocating the primacy of the senses, Telesio was the first empiricist of the early modern era. He made his empirical point in a book, De rerum natura iuxta propria principia (On the Nature of Things according to their Own Principles), which was first published in Naples in 1565, expanded in 1570, and given its final form in 1586. Granted, having had a great insight, Telesio had to spoil things, by breaking his own rules and reasoning upon such things as the nature of matter, but we forgive him for that – natural philosophers cannot help thinking, even as it leads them into error. Fortunately, lots of followers only read the first few pages of his book and came away with the idea that we should learn about the world through observation and experiment, and that was his key contribution to 17th-century science.

In addition to inspiring Bruno and Campanella, who were much influenced by their fellow Neapolitan (Campanella titled his first book, Philosophia sensibus demonstrata, [Philosophy demonstrated by the senses], 1592), Telesio had a noticeable impact on Francis Bacon in England, who in the early 17th century was also taking aim at Aristotle and ancient natural philosophy, and formulating his own scientific method, a form of induction based on observation and experiment. Bacon recognized that he had been anticipated by Telesio, whom he called the first of the moderns.

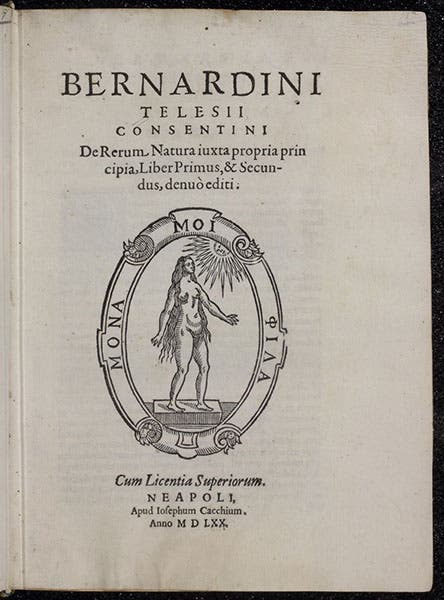

We have in our library a lovely copy of the 1570 edition of De rerum natura. It contains three other short works by Telesio, so one is tempted to call it a sammelband, but it is apparent that the printer published all four works simultaneously and sold them as a unit, which disqualifies it as a sammelband, which is a collection of works bound together later, usually by the owner, not the printer. Still, it is a handsome thing, in its contemporary vellum binding (third image). The device on the title page, depicting a nude woman illuminated by the Sun, has sometimes been assumed to be an emblem of Telesio, but it is a printer’s device and has nothing to do with Telesio. The Greek motto, Mona moi phila, defies easy translation, but the image would seem to derive from the theme of “Truth revealed,” used by several printers. It appears on all the titlepages in this volume.

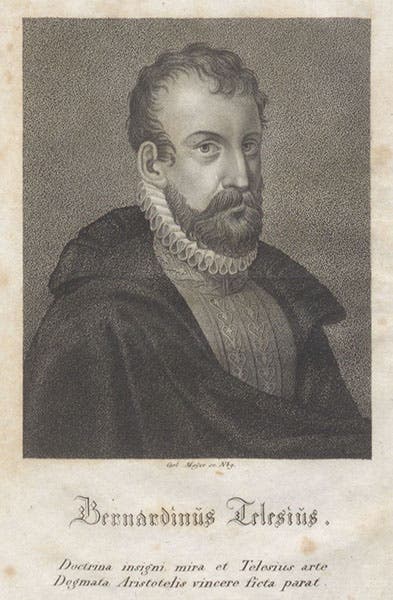

Finding a contemporary portrait of Telesio has not been a rewarding task. There is a wonderful aquatint in an early nineteenth century history of physical science that we have, and it is fully 200 years old, but it is hardly contemporary (first image). There is also a handsome statue in Telesio’s hometown of Cosenza, where he is something of a celebrity figure (fourth image). Since we have little in the way of graphics for today’s post, we add a modern view of the old town of Cosenza (fifth image). No wonder Telesio returned to Cosenza whenever he could, and died here, on this day in 1588.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.