Scientist of the Day - Brook Taylor

Brook Taylor, an English mathematician, was born Aug. 18, 1685. Although he is seldom mentioned in general discussions of mathematics in the early calculus era, where Isaac Newton, Gottfried Leibniz, and various Bernoulli’s seem to garner most of the attention, Taylor had as much mathematical aptitude as any of his more famous contemporaries, and these contemporaries knew it, giving Taylor a great deal of respect.. Taylor published two influential books in 1715. The first had the scintillating title: Methodus incrementorum directa et inversa (Direct and inverse methods of increments), and dealt with the new branch of mathematics – calculus – which was invented by Newton (if you lived in England) or Leibniz (if you lived on the continent).

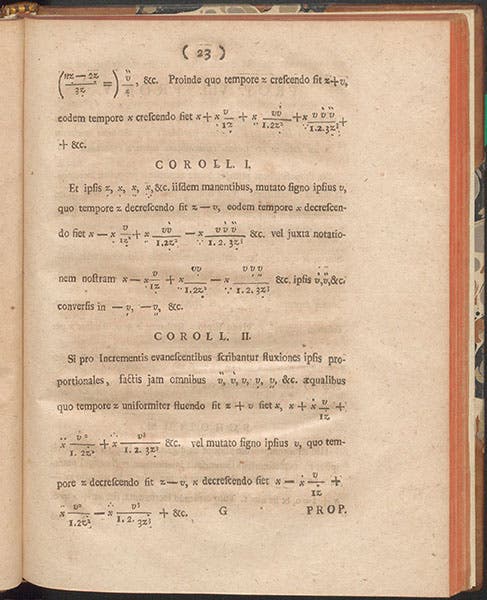

In his Methodus, Taylor developed what is now known as the calculus of finite differences. He also proved an important principle of this calculus, called Taylor's theorem, which involves expressing differentials as an infinite series. I could not explain Taylor's theorem to anyone, but I can show you the page in his book where Taylor set down his theorem – it is in corollary 2 in our third image. Taylor used a elaborate system of dot-nomenclature to denote his differentials, which makes it even more difficult for the modern mathematician to follow. Since I am not a modern mathematician, I don't have to. But we are happy to have Taylor's book in our collections, since historians of mathematics, who know all about Taylor, are always happy and pleased to see it.

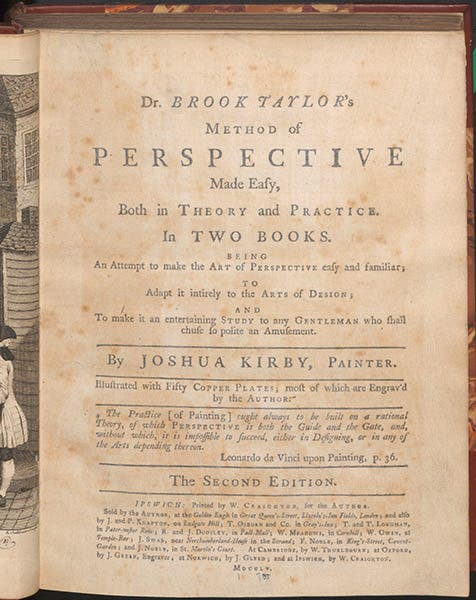

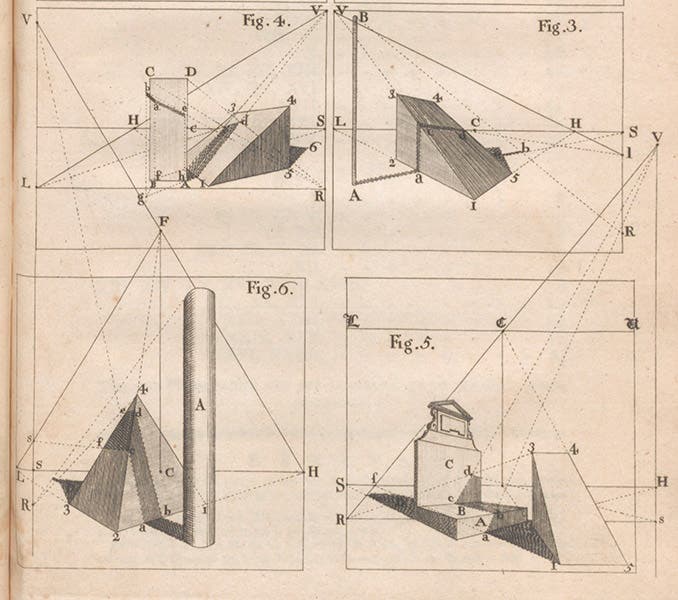

The other Taylor publication of 1715 was called Linear Perspective, and it was an attempt by a mathematician to instruct artists and architects in the proper techniques of perspective. We do not own this first edition, which is said to be brilliant but murky, since Taylor was not a gifted writer. Fortunately, an artist named Joshua Kirby decided to teach Taylor’s techniques to an audience of artists, and he published Dr. Brook Taylor's Method of Perspective, Made Easy, in 1754. It was a best-seller, and a second edition was required in 1755, which is the edition we have. The work is illustrated with dozens of engraved plates containing scores of figures, all drawn by Kirby and making it much easier to understand Taylor's methods (fifth image).

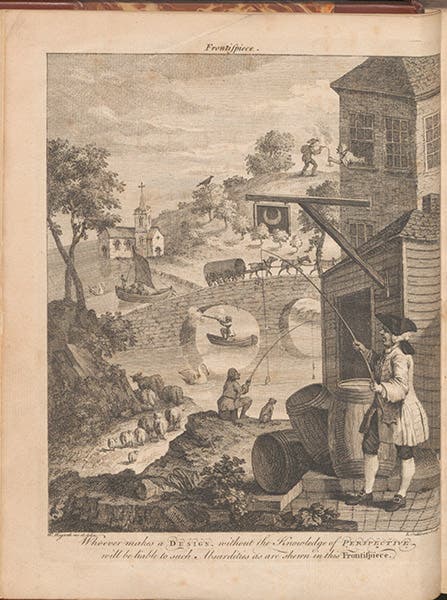

The most unusual feature of Kirby’s book is the frontispiece, designed especially for this occasion by the satirist William Hogarth, who was a good friend of Kirby (sixth image). It is often referred to as Hogarth’s “False Perspective.” For any modern viewer, it calls to mind the paradoxical constructions of Maurits Escher, in that much of what is depicted is physically impossible. The caption, engraved at the bottom, says: “Whoever makes a Design without the Knowledge of Perspective will be liable to such Absurdities as are shewn in this Frontispiece.” There are at least thirty perspective errors in Hogarth’s drawing – we include a detail so you can more easily pick out a few of them (seventh image).

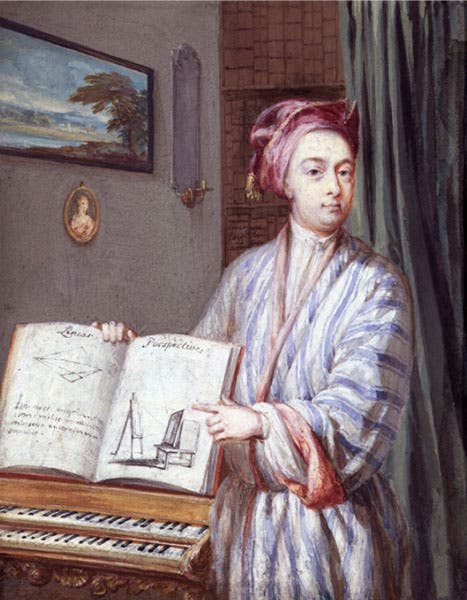

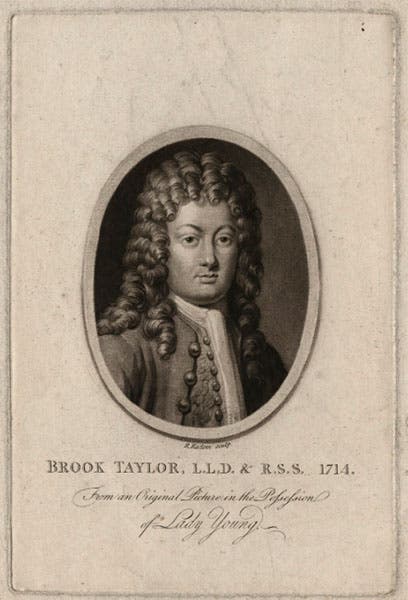

There are two surviving portraits of Taylor, and since they do not look much like one another, we thought we would show you both. The first is a small watercolor, painted on vellum pasted to a card, and depicts Taylor pointing to his book, Linear Perspective (first image). The second is a posthumous mezzotint, engraved after a portrait by an unknown artist (eighth image). Both portraits are in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.