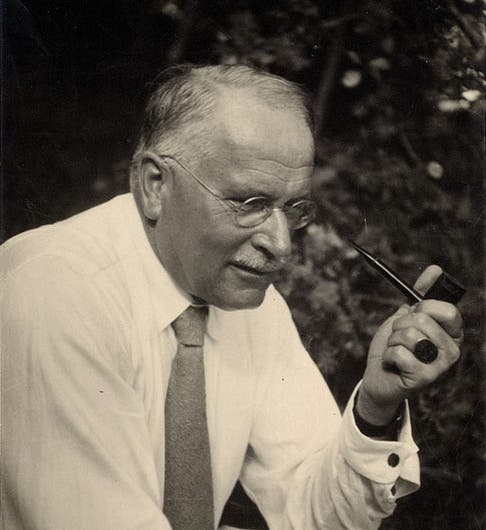

Scientist of the Day - Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung, a Swiss psychologist, was born July 26, 1875. Jung was one of the founders of psychoanalysis, and he taught (and listened) for many years in Zurich and Basel. Psychoanalysis as a science is outside our scope, and beyond my expertise, but I thought it might be interesting to examine Jung’s relationship with and influence on one of the great 20th-century figures in quantum mechanics, Wolfgang Pauli.

We published a post on Pauli three years ago, in which we discussed his "exclusion principle," for which he postulated a fourth quantum number, called "spin," as well as his proposal that there must be an undiscovered particle that carries away some of the energy in beta decay. He called his new particle a "neutron;" that word was later used for a different new particle, but Pauli's proposed particle was eventually discovered, and called a "neutrino," which is a much better word than neutron for a mere wisp of a thing.

All this was by 1930, at which time Pauli entered a physicist's "old age," turning 30, and life began to grow sour. His mother killed herself when his father had an affair. Pauli had a brief marriage with a nightclub singer, started drinking too much, and was belligerent with colleagues. And he started having strange dreams. Pauli was now teaching in Zurich, where Jung also spent considerable time, and Pauli asked Jung if he could help with the dreams. Jung did not want to get involved personally, but he arranged for Pauli to have sessions with a young assistant, for whom Pauli started writing down his dreams. He eventually recorded over 400 of them, and Jung used a number of them in a book, Psychology and Alchemy (1944), taking pains (at Pauli's request) to keep his identity a secret, concealing even the fact that the dreamer was a physicist. In 1932, the two began a correspondence, which lasted for 26 years. The letters, 80 of them in all, have been published, as Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932-1958, edited by C.A. Meier (2001), that you can find in our library. We also have The Cosmic Number: The Strange Friendship of Wolfgang Pauli and Carl Jung, by Arthur I. Miller (2009), for those interested.

One of the topics the two discussed was “synchronicity,” a term coined (I believe) by Jung to refer to phenomena that appear to have a connection but for which there is no causal explanation. The famous "Pauli effect," whereby experiments go wrong if Pauli is even in the general vicinity, although often treated facetiously, is an example of synchronity, and is discussed several times in their letters. Pauli was interested because one of the consequences of quantum mechanics is the loss of causality. Two particles, in theory, can influence each other over immense distances in ways that cannot be explained by conventional forces. Another Jungian concept that intrigued Pauli was the "collective unconscious," whereby humans share concepts – “archetypes" – of which they are not even aware.

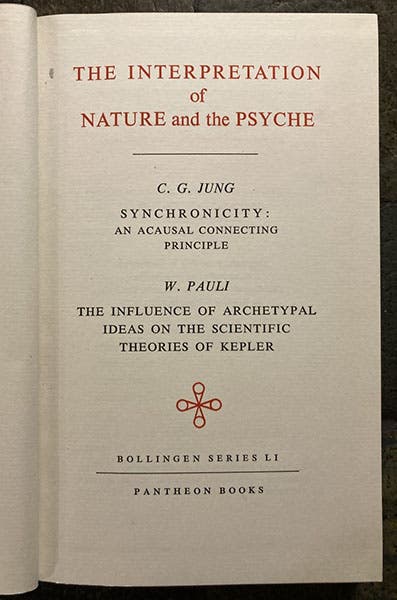

Title page of The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche, by C.G. Jung and W. Pauli, 1954 (author’s collection)

One of the most interesting byproducts of the Pauli-Jung relationship was a book, published in German in 1952 and in English in 1954 as The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche. It contains two parts; the first, written by Jung, has the title: “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle”, and the second part, by Pauli, is called: “The Influence of Archetypal Ideas on the Scientific Theories of Kepler.” The Pauli essay is quite well known to historians of Kepler (as I am sure the Jung essay is to historians of psychoanalysis). Pauli was not a historian, but he acquitted himself well, reading Kepler in the original Latin (and German). Pauli's thesis was that Kepler welcomed the heliocentric theory of Copernicus because of the archetype of the Trinity, the "Threeness of things." Kepler saw the universe as a geometric construction – and God as a Geometer – and he embraced the sphere as the most perfect shape for a cosmos. In the sun-centered universe, God is the Sun at the center, Christ is the surface of the sphere, and the Holy Spirit fills the intervening space. In a famous conflict with Robert Fludd, an English Rosicrucian, Kepler objected to Fludd's reliance on the archetype of "Quaternity," seeing everything in patterns of four, as Aristotle did with his four qualities and four elements, and rejecting the Copernican system. The Kepler-Fludd debate was, to Pauli’s mind, a battle of archetypes. In Pauli's view (and Jung's), these archetypes are not human constructions, but are real entities, built into the fabric of things, that all humans share and have access to, and which influence our thoughts and actions.

Jung also followed with great interest the experiments on ESP of J.B. Rhine at Duke University. Jung believed the results clearly showed that some people have access to forms of perception that others lack. This would be an interesting topic for further discussion, by someone better acquainted than I with Jung and with the claims of parapsychology.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.