Scientist of the Day - Carl Linnaeus

Carl von Linné, a Swedish botanist and taxonomist better known as Linnaeus, was born May 23, 1707. We have written two posts on Linnaeus, one in 2017, the second just last year, when we focused on his "sexual system" of plant taxonomy, and discussed it in some detail. Today we merely continue the discussion, with two special added features, which will become evident in a moment.

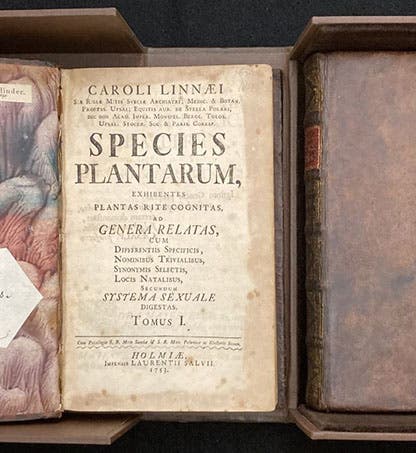

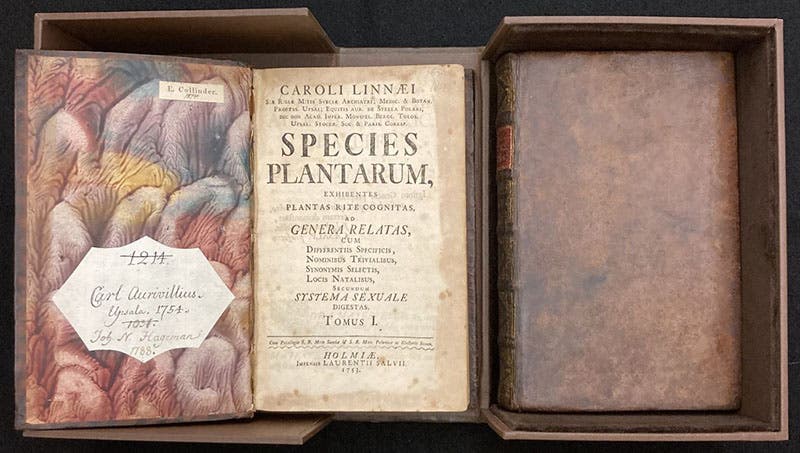

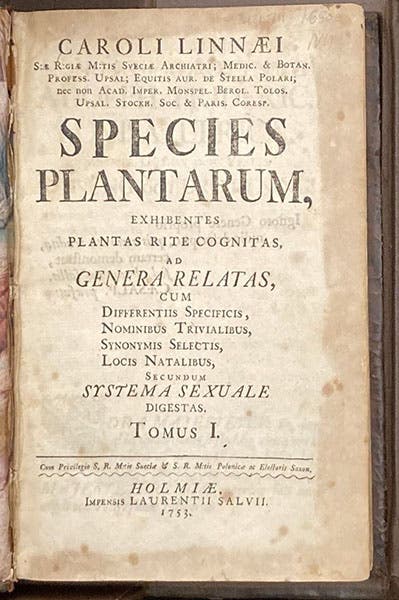

In our last post, we said that the basic text for Linnaeus' botanical taxonomy was his Species plantarum, published in 2 volumes in 1753. It listed over 5900 species of plants from around the world, giving each a binomial name that was unique. It is the starting point, year 1, for subsequent botanical nomenclature. If a plant appeared in that book with a binomial name, it has that name still. Nothing before 1753 counts, in the world of botany. So this is a very special book. And on this day in 2024, I noted that while we have the 10th edition of Linnaeus' Systema naturae (1758-59), the starting point for zoological nomenclature and taxonomy, we did not have the Species plantarum of 1753 in our collections.

One year later, things are different. This spring, Jason Dean, our rare book librarian, acquired the Species plantarum from Sotheran’s in England for our history of science collections. You have been looking at photos of our new arrival as you read this far, and you will see a few more before you're done.

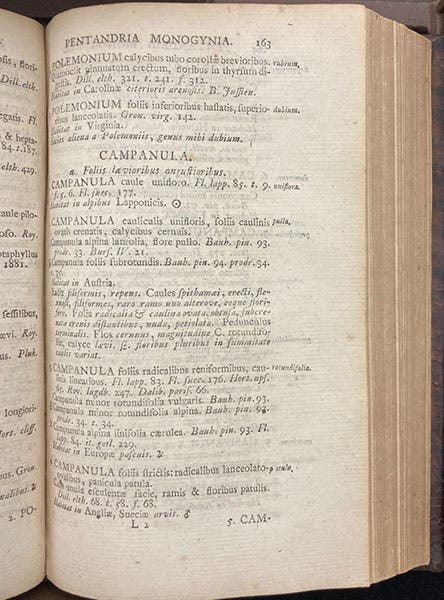

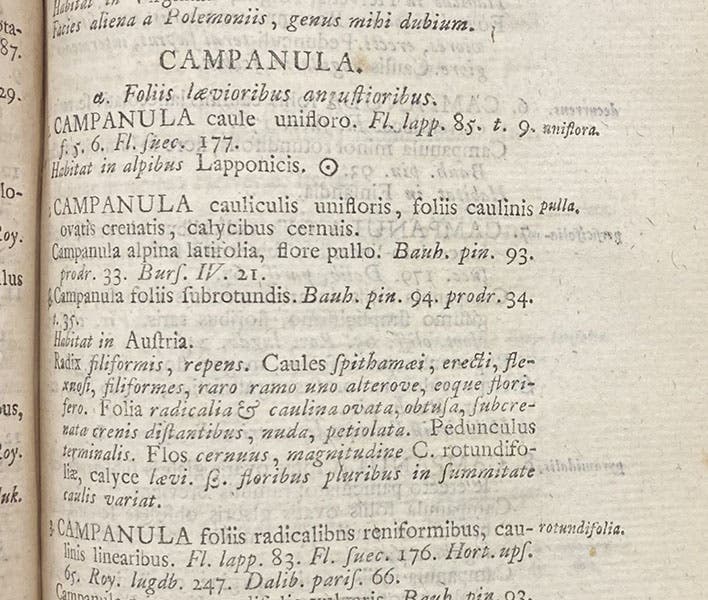

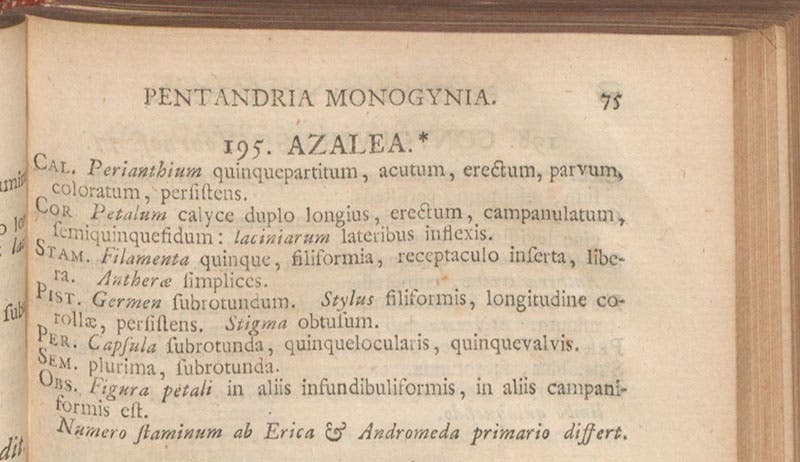

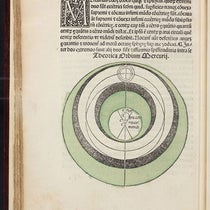

Neither volume of the book is illustrated – this is not a flora – so all we can show you is a sample page of text (fourth image; detail in fifth image). You will note that every species has a two-word Latin name (the species name is at the right, in italics), making the Species plantarum the first botanical book to make consistent use of binomial nomenclature, and the starting point for all modern botanical nomenclature.

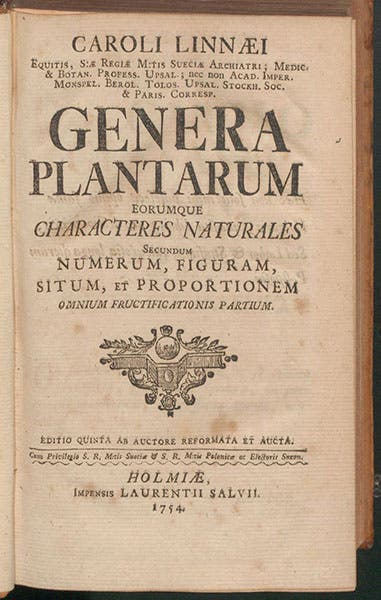

You might also notice that there are no definitions for genera in the Species plantarum – they are taken for granted. That is because Linnaeus had already published a Genera plantarum (1737), defining 935 different genera. To accompany the Species plantarum, Linnaeus published a new edition of the Genera, now with 1105 genera, so that the lists in the two books would match. The Genera of 1754 is in a sense the mate of the Species of 1753, so they belong together, and it was thoughtful of Jason Dean to acquire the Genera plantarum at the same time. So now we have both. And they seem happy in their new home (sixth and seventh images).

The only significant Linnaean item still lacking from our collections is the first edition of the Systema naturae, published in 1735, when Linnaeus was 28 years old. It is a mere 12-page pamphlet, with the entire plant kingdom outlined on two facing pages, and the animals on the two pages after that. It marks the birth of the kingdom-class-order-genus-species taxonomic hierarchy. I have never seen a copy on the market, and should one appear for sale, we could never afford it. But it would be something to have it alongside the Species plantarum and the 1758-59 Systema naturae on the shelves of our vault.

In our first two posts on Linnaeus, we showed six portraits and a statue of the great classifier – he was an often-depicted fellow. For this post, we sought something different, and chose a jasperware portrait medallion crafted for sale by the pottery firm of Josiah Wedgwood of Staffordshire in 1775 (second image). One of the great champions of Linnaean botanical taxonomy in England was Erasmus Darwin of Lichfield. Darwin's son Robert and Wedgwood's daughter Susannah were married in 1796, and in 1809, Susannah gave birth to son Charles, who would bring what was left of the Linnaean sexual system (but not the nomenclature) crashing to earth in 1859. Small world, indeed.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.