Scientist of the Day - Carl Schwachheim

On Aug. 29, 1927, Carl Schwachheim, a blacksmith turned amateur archaeologist from Raton, New Mexico, found a projectile point nestled between the ribs of an extinct bison at an excavation in Folsom, New Mexico. The site at Folsom, in the northeast corner of the state, had been discovered years earlier by a black American cowboy, George McJunkin, who found there, washed out by a flood, some bison bones that were larger and sturdier than normal. He told various people about the site, but no one was interested enough to investigate, and McJunkin died in 1922 without any further discoveries being made at Folsom.

One of the people McJunkin told about Folsom was Schwachheim, who decided, after McJunkin's death, to take a look. He persuaded a friend with a car to drive out to Folsom from Raton, where they located the large prehistoric bison bones and realized that this might be a promising archaeological site.

Some time later (1926), when the two men were in Denver, they stopped by the Colorado Museum of Natural History and told the director, Jesse Figgins, about their find. He called in his paleontology expert, Howard Cook, and they asked to see some samples, which Schwachheim subsequently sent them. Cook declared the bones to be those of Bison antiquus, an extinct Pleistocene herbivore, and the ancestor of the modern plains bison. All agreed that Folsom was a site worthy of excavation, and Schwachheim was apparently put in charge. He was told to look for evidence of human presence at the site, which would probably consist of stone spear points, which archaeologists prefer to call projectile points. He was also apparently told not to remove any such points, should he find them, but leave them in situ and notify Figgins and Cook immediately, and they would send an archaeological team to the spot.

Several points had already been found in 1926, but none were in situ, until Schwachheim uncovered, on this day in 1927, his pair of Bison antiquus ribs with a stone point between. He dutifully covered up his find and telegraphed Figgins, who put out a call for expert witnesses who could verify Schwachheim's discovery.

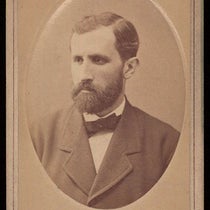

The first to arrive were Barnum Brown, an eminent paleontologist from the American Museum in Natural History, who had discovered the first T-Rex in 1902, and Alfred Kidder, a distinguished archaeologist, who just happened to be attending (in fact, organizing) the very first Pecos Conference at nearby Pecos, New Mexico. They arrived in early September, verified the in situ status of the point, and the press was called in to take photos for a press release; we show one, with Schwachheim at the left, pointing out the location of the ribs to Brown (third image). Witnesses, especially expert ones, can make all the difference when extraordinary claims are made.

The find was a big deal, because before Folsom, there was no evidence for human presence anywhere in the Americas during the Pleistocene era, which ended about 11,800 years ago. The Folsom point was the first evidence that Paleoindians, as they were called, had indeed been present, and had hunted Bison antiquus. So the site, and the projectile point, and the date would become quite famous in archaeological lore. Excavation began in earnest, with various people, like Figgins, and Howard, and Brown, seeking credit for the discovery of human presence in Pleistocene America, but I prefer to shine the light on Schwachheim, who deserves it more than anyone else.

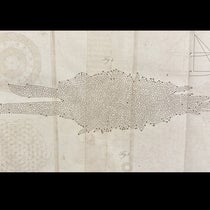

The name Folsom has since been applied to an entire culture and tool industry that flourished over much of North America for 400 years, beginning about 12,600 years ago. Folsom points, as they are called, are quite distinctive, with large flutes removed to accommodate insertion into a shaft (fourth image). The two ribs and the in situ point uncovered at Folsom were cut out and shipped to the museum in Denver, now the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, where the block is on display, although with surprisingly little fanfare about the significance of the find as a turning point in the history of American archaeology. That, at least, was the case the last time I was there, and I can find no recent photos to indicate that things have changed.

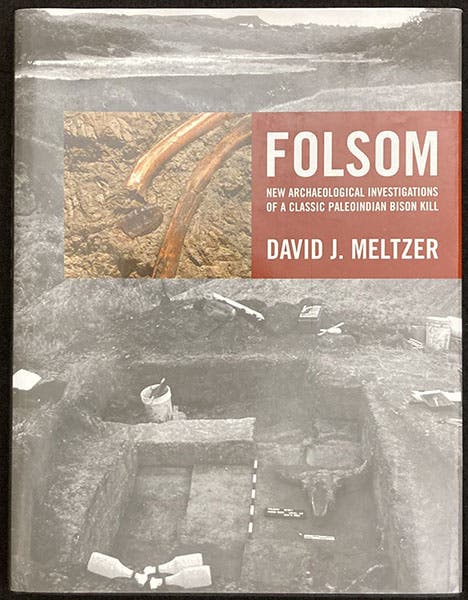

Dust jacket, Folsom: New Archaeological Investigations of a Classic Paleoindian Bison Kill, by Donald J. Meltzer (Univ. of California Press, 2006), with a color photo of the Folsom point in situ next to the title (author’s copy)

In the 1990s, Folsom was re-excavated by a team led by Donald Melzer of Southern Methodist University, and Melzer published the definitive book on the site in 2006, called Folsom, with a long subtitle. I bought the pricey, oversize book for some reason, perhaps because the Library did not do so. The dust jacket (last image) shows the only circulating photo of the Folsom point in situ at the top, as well as a 1998 photo of Meltzer’s careful excavation; it is interesting that the photo of the early find is in color, and that of the later in black-and-white, a no-doubt intentional reversal of the usual state of affairs.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.