Scientist of the Day - Charles Blagden

Charles Blagden, an English physician, chemist, and scientific diplomat, was born Apr. 17, 1748. He studied medicine at Edinburgh, where he took chemistry courses from Joseph Black. Blagden was invited into the fellowship of the Royal Society in 1772, about the time that Joseph Banks, freshly returned from Cook's first voyage and a trip to Iceland, was rising in the world of London science, and the two must have come into contact early, as they became lifelong friends. Blagden read several papers to the Society before heading off to serve as ship’s physician in the Revolutionary War. When he returned in 1780, he moved to London and began to take a more active role in the Royal Society, of which Banks was now President. When the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, wanted to visit an unknown musician in Bath, William Herschel, who was also an amateur telescope maker, it was Blagden who went along as intermediary. He must have hit it off with sister Caroline, for when she discovered a comet six years later, she sent the letter of announcement to Blagden.

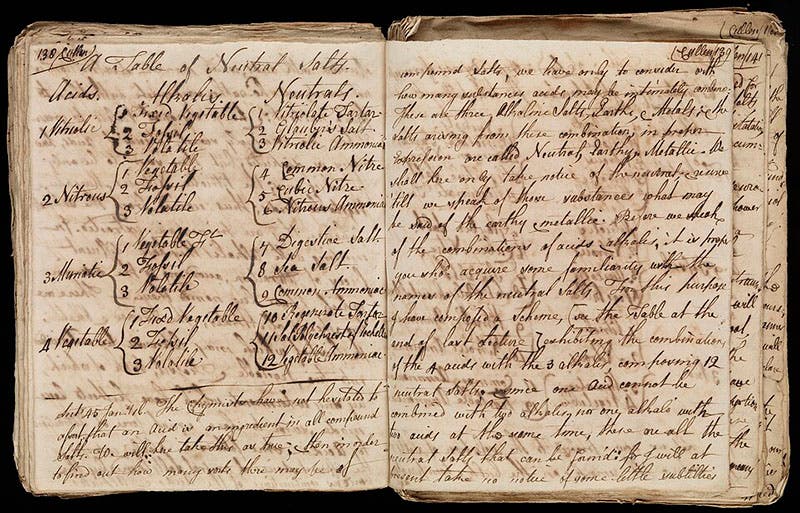

First page of paper, “Experiments and Observations in a heated room,” Charles Blagden, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol. 65, 1775 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1782, before he formally became Banks' assistant at the Royal Society, Blagden worked as assistant to Henry Cavendish, who was investigating the recent claims of Joseph Priestley to have made water by burning combustible air (hydrogen). Cavendish confirmed the experiments in 1783, just after the Peace of Paris was signed and scientific exchanges between French and English were possible again. So off Blagden went to Paris, to tell members of the French Academy what English chemists were up to, and just in time to see Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace do their own more elaborate experiments, burning hydrogen with pure oxygen and producing measurable amounts of pure H2O, which Lavoisier explained with a radically new theory of combustion, the oxygen theory. Blagden recounted all this in letters to Banks.

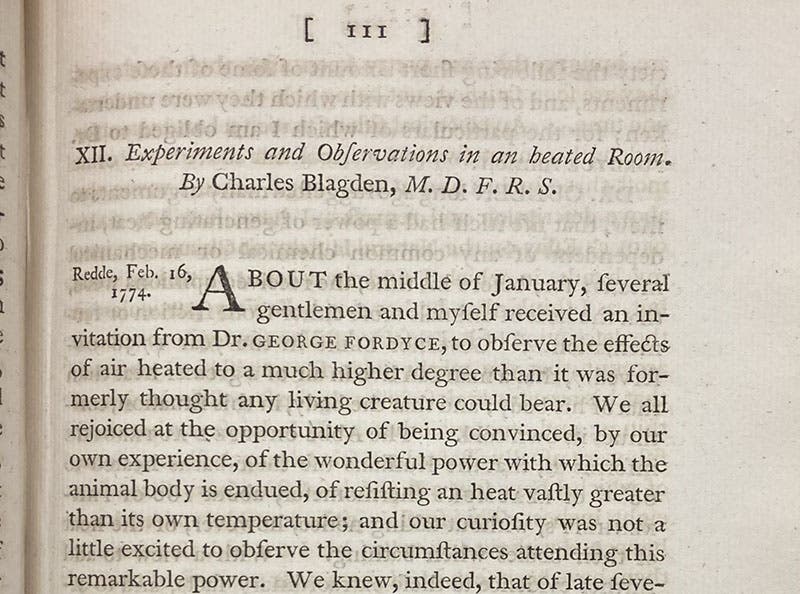

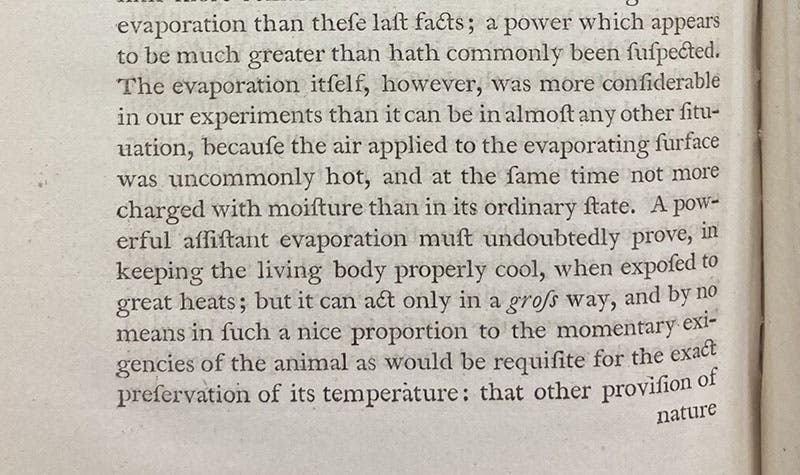

Paragraph revealing the role of perspiration in cooling, “Experiments and Observations in a heated room,” by Charles Blagden, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol. 65, 1775 (Linda Hall Library)

Blagden made at least four extended trips to France during the course of his life, and would have made more, were the English and French not constantly at war. He became close friends with the noted chemist Claude Berthollet, and stayed several times at his estate at Arcueil. In fact, he died there on his last visit, on Mar. 26, 1820, three months before Banks died back in London. Blagden, unusually for an Englishman, was buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery, where many great French scientists, such as Laplace, have been laid to rest.

Blagden is a good example of what we might call a scientific diplomat, someone who facilitates the exchange of ideas, especially between individuals of different cultures. They are essential for scientific growth, and few did it as well as Blagden. He was, however, quite capable of original scientific work on his own. In a memorable pair of papers, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, he showed that humans can withstand much higher temperatures than previously thought, over 200° F, without suffering much of a rise in body temperature. It was during these experiments that Blagden discovered the role of the evaporation of perspiration in cooling the body. We Include here a photo of the first page of the first article, and of the paragraph where sweat finally gets its due (second and third images).

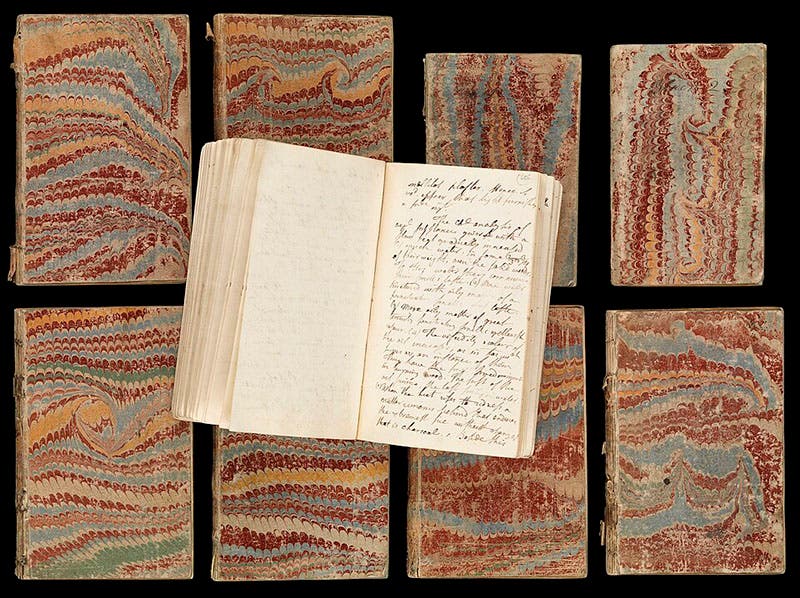

The Royal Society has quite a collection of Blagden's papers and correspondence, and the Wellcome Institute in London has his lecture notebooks from Edinburgh. I don't know what your college notebooks looked like, but mine were nothing like this (fourth and fifth images).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.