Scientist of the Day - Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin, everyone's favorite English naturalist, was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Shrewsbury, England. Darwin was co-discoverer, with Alfred Russel Wallace, of evolution by natural selection, and author of On the Origin of Species (1859), perhaps the most revolutionary and influential book ever published in the natural sciences. We have published three anniversary notices about Darwin in this series: one on the publication of the Origin of Species; another about his funeral, and a third concerning Darwin portraiture. We have not yet, shockingly, written about the voyage of HMS Beagle, and we will do so at the next opportunity. But today we are going to discuss the aspect of Darwin’s career that is least appreciated by the general public – his protracted study of barnacles. Darwin spent 8 difficult years becoming the world's expert on these crustaceans, and this was before he wrote the Origin of Species. Those 8 years marked his transformation from a naturalist into an invertebrate zoologist and taxonomist, and also provided many examples of how natural selection works. It is probable that without the barnacle studies, the Origin would have been a different book. It is certain that it would have had a much less favorable reception.

Darwin first encountered barnacles in the Firth of Forth, in his years at Edinburgh, when barnacles were still thought to be mollusks like clams and snails. One of his teachers, Robert Grant, was an invertebrate zoologist (and an early evolutionist). Darwin encountered more of them on the Beagle voyages, 1831-36, although he doesn’t seem to have collected many of them, at least not the ordinary kind. But in January of 1834, he ran across an unusual kind of barnacle almost by accident, which he decided to bring home in a specimen jar. These were tiny barnacles, without shells, that he found in a conch shell that he picked up on a beach in Chile. The shell was pocked with minute holes, and in each was a miniscule barnacle. He dug out a dozen or so, put them in a specimen jar, and they travelled home with Darwin, along with some 1500 other specimen jars with mysteries of their own.

Twelve years later, in 1846, Darwin had published his account of the Beagle voyage (his "diary", but not really), and five volumes called The Zoology of the Beagle. He had published two volumes about the geology of the Beagle voyage and had a third in press. He had also written two preliminary accounts of his theory of evolution by natural selection: his "Sketch" of 1842 and his "Essay" of 1844, but these were in a drawer and were not to be seen by anyone other than his closest friends unless he died prematurely.

Darwin had distributed many of the specimens brought home from his voyage to experts in various fields, but there were no barnacle experts, so the jar from Chile had stayed on his shelf. It was one of the few remaining from the voyage. On Oct. 1, 1846, Darwin sat at his microscope and opened the jar containing the mini-barnacles from Chile. He teased one of them apart under his microscope and was amazed at what he saw. He didn't understand any of the anatomy. But he did give it a nickname: Mr. Arthrobalanus the jointed barnacle. He wrote to his friend Joseph Hooker, and Hooker was a receptive ear, but Hooker was a botanist and unlikely to solve problems with barnacle taxonomy. But Hooker did know that barnacles were a mystery to everyone, and he encouraged Darwin to engage in a study on his own. Darwin thought that was a good suggestion. He thought he would be done with the matter in a month.

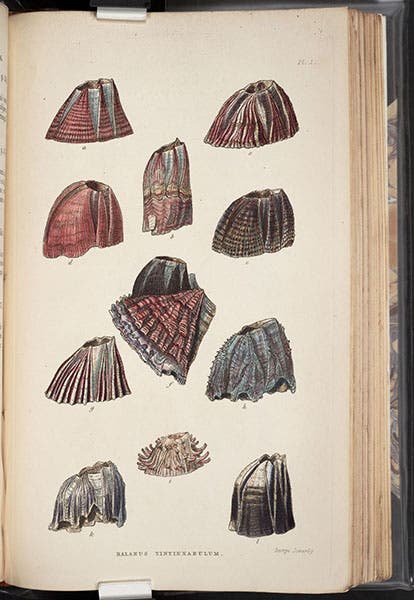

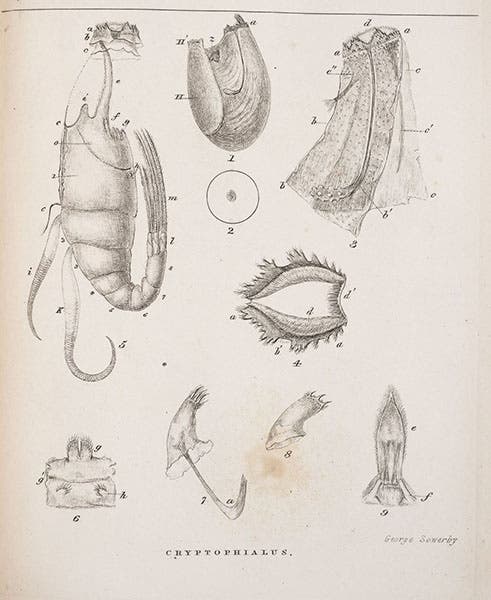

First plate with details of Cryptophialus (Mr. Arthrobalanus); fig. 1 is the complete female, and fig 2 is the tiny male, shown as “z” in fig. 1; engraving by George Sowerby, in A Monograph on the Sub-Class Cirripedia, with Figures of All the Species, Vol. 2: The Balanidae, by Charles Darwin, 1854 (Linda Hall Library)

Darwin would need barnacles to study. Since he was essentially an invalid, or considered himself one, the barnacles had to come to him. So he wrote to anyone and everyone who might have a barnacle collection and begged to borrow their specimens. Many correspondents obliged, and soon barnacles were arriving at Down House from all over the globe. He even persuaded the British Museum to lend him their entire barnacle collection. Darwin plunged into these uncharted waters, a Barnacle Bay of misunderstood invertebrates, and he wouldn't return to shore for nearly eight years.

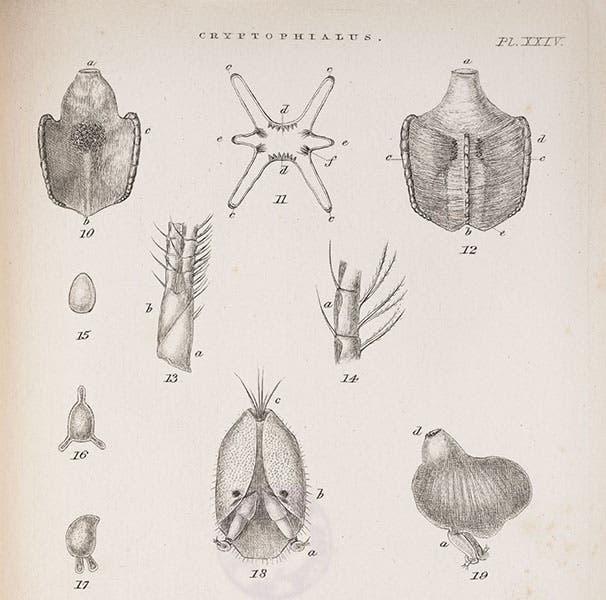

Second plate with details of Cryptophialus (Mr. Arthrobalanus); fig. 19 is the tiny male, visible only under a microscope (see next image for detail); engraving by George Sowerby, in A Monograph on the Sub-Class Cirripedia, with Figures of All the Species, Vol. 2: The Balanidae, by Charles Darwin, 1854 (Linda Hall Library)

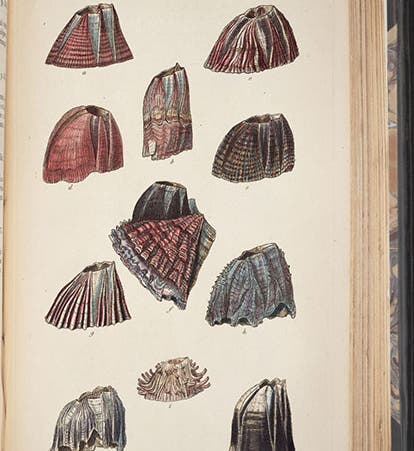

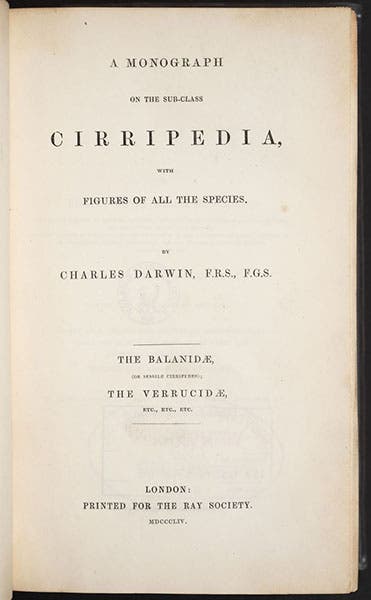

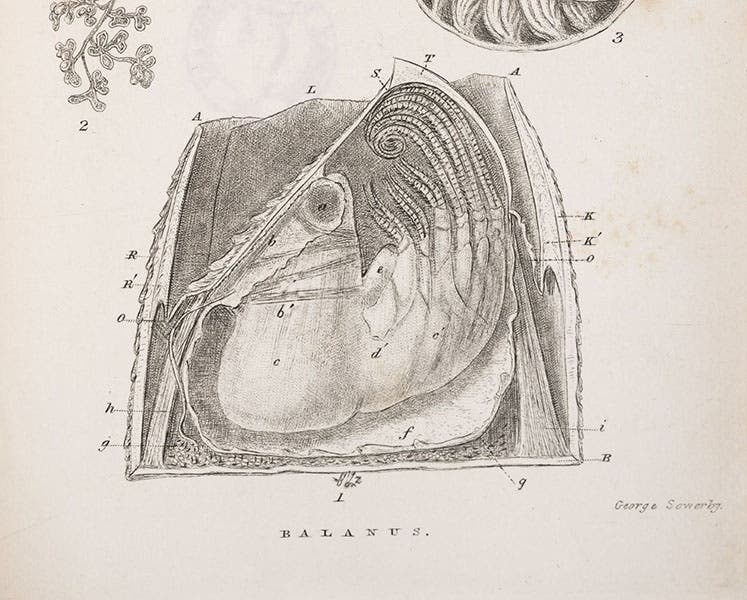

This is not the place to provide details of what Darwin learned about barnacles. But he did become the world’s foremost expert on Cirripedia, a subclass of the subphylum of Crustacea in the Arthropod phylum. He published four volumes on Cirripedia between 1851 and 1854, two on living species, and two on fossil barnacles, in which he reworked the taxonomy of the entire group. We have all of them in our collections. The second volume on living species discussed and classified Balanidae, the sessile barnacles (the ones that attach themselves to rocks). As the title states, it has figures of every species, drawn by George Sowerby, who came to Down House to do so. There is a handsome (but not typical) hand-colored engraving that opens the plate section (first image), and a final one that provides a cross-section of an acorn barnacle (fourth image). Darwin asked Sowerby to illustrate Mr. Arthrobalanus, which he now named Cryptophialus minutus. There are 19 drawings of Cryptophialus on two engraved plates (fifth and sixth images). It turned out that Mr. Arthrobalanus was actually Ms. Arthrobalanus, and her mate was a tiny parasite, shown as “z” on fig. 1 and again, circled, as fig. 2 (fifth image), and finally, enlarged from a microscopic dot, as fig. 19 on the second plate (sixth and seventh images). Darwin managed to sort all this out, not just for his Chile barnacle, but for every barnacle he studied. It was a massive undertaking. And it was very well received in the scientific community, by the likes of Hooker, Thomas Huxley, Asa Gray, and even Richard Owen. Darwin had earned the right to speak as an authority.

Darwin has sometimes been criticized for spending 8 years taking apart barnacles, when he should have been writing the Origin of Species. But before his barnacle encounters, he had no professional acquaintance with the nuts and bolts of taxonomy. Nor did he understand how pervasive variation was in the natural world, and without variation, there can be no natural selection. In 1844, an anonymous author (now known to be Robert Chambers) had published The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, proposing a theory of evolution. Although popular with the public, it was booed off the scientific stage, and the typical charge was: the author knows nothing about species or taxonomy. When the Origin of Species appeared, many did not like the theory it proposed. But no one accused Darwin of not knowing what he was talking about, when it came to species and variation. He had earned his stripes.

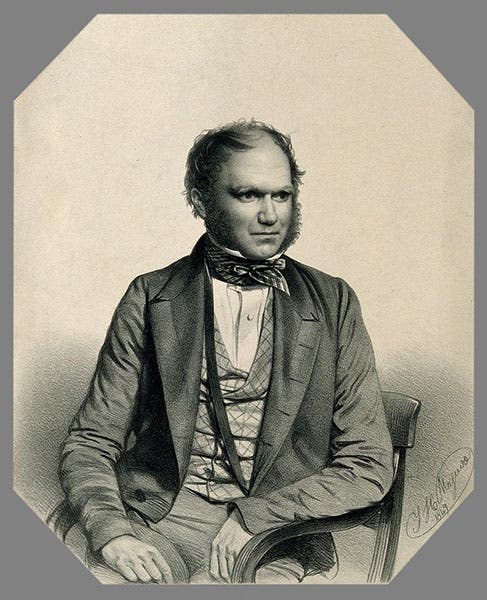

Our portrait of Darwin, my favorite, shows Darwin as he appeared in 1849, three years into his barnacle studies. It was lithographed by Thomas Maguire. We show the print in the Wellcome Collection in London (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.