Scientist of the Day - Charles de Rochefort

Charles de Rochefort, a French Huguenot minister and missionary, was born in 1605 and died in 1683. He spent at least a decade in the Caribbean, from 1636 to the mid- 1640s, on Tobago and what we now call St. Kitts, before returning to take up a post as minister at a Huguenot Church in Rotterdam, a position that he held the rest of his life. In 1658, a book was published in Rotterdam, called Histoire naturelle et morale des iles Antilles de l'Amerique. The only name mentioned in the preface was “M. de Rochefort”. For a long time, this was suspected to be either Cesar de Rochefort or the comte de Rochefort. But in 1992, a scholar convincingly demonstrated that the author was Charles de Rochefort, the Huguenot minister of Rotterdam.

The Natural and Moral History of the Antilles was a very popular book. There were six separate issues of the work in 1658 alone; our copy seems to be the fourth issue. There were soon translations into other languages, including English in 1666. From the title, one might gather that Rochefort's book was akin to Willem Piso's Natural History of Brazil (see our post on Georg Markgraf), which had been published in 1648 (and which may have provided some of the animal images in Rochefort's book). In fact, the intent here was quite different. Rochefort's book was written for the principal purpose of convincing other Huguenots to emigrate to the Caribbean. It described the islands and the natives in glowing terms, to make the Antilles seem a desirable destination for Protestants living in a France that didn't want them and barely tolerated them.

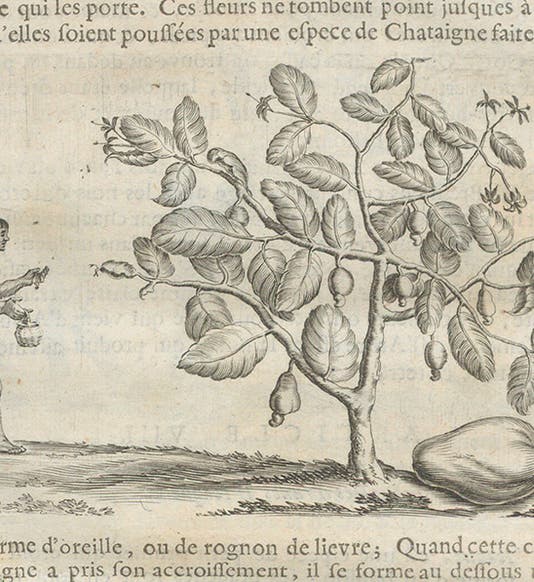

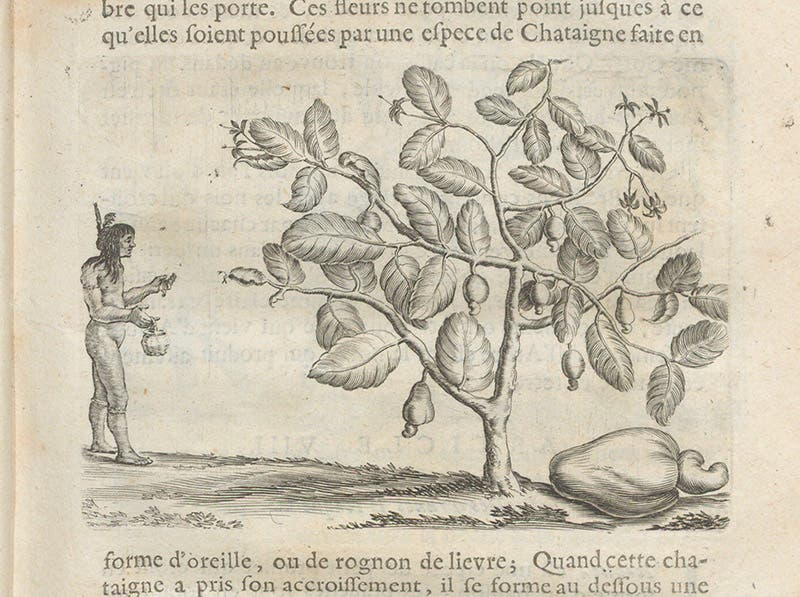

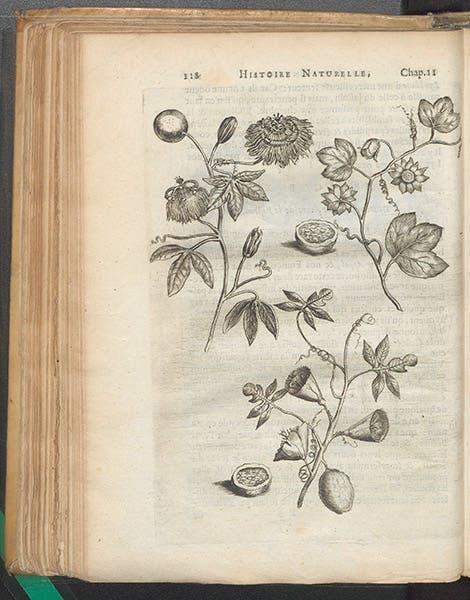

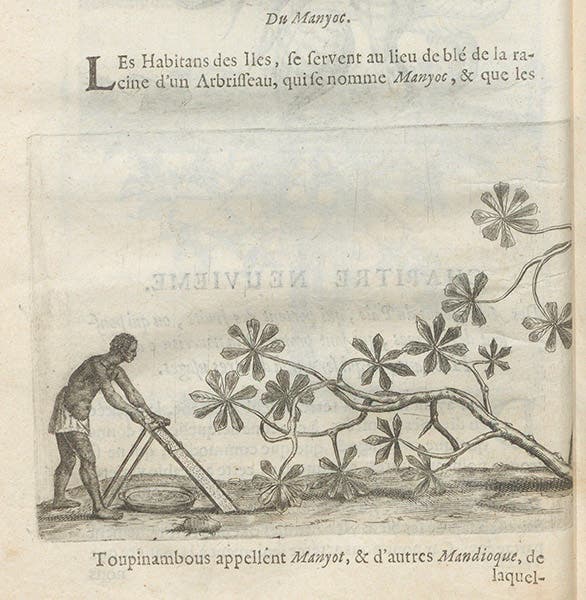

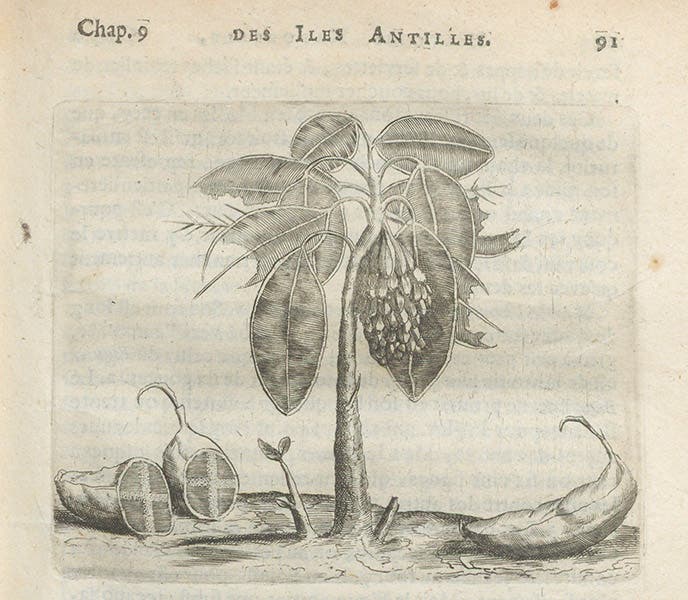

The missionary purpose notwithstanding, Rochefort was very good at describing the flora and fauna of the Antilles, especially the plants. And he provided attractive engravings of many of the tropical plants he described. We show several of those illustrations here. You will notice that Rochefort, unlike Piso, liked to depict natives interacting with the plants, which makes his engravings even more attractive, from an ethnological point of view.

One of the plants Rochefort illustrated was the cashew. The cashew had appeared in several natural history books prior to this one, but it was often depicted incorrectly, with the nut between the stem and the apple. Rochefort (or his artist) got it right, with the cashew nut at the free end of the apple (first image).

Another attractive image is a full-page engraving that shows both the passionflower and the passion fruit (fourth image). Most later illustrators show only the beautiful flower.

The illustration of the manioc plant, which is a half-page engraving, is another one of those that shows how the native peoples used the root, or at least made it useable by shredding it on a giant grater (fifth image). Notice another unshredded root on the ground in front of the worker.

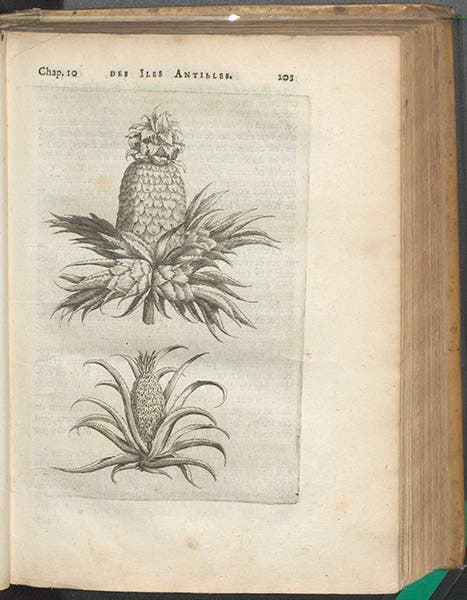

The other engravings we reproduce depict two varieties of pineapple (sixth image), and a banana tree with fruit, which Rochefort actually calls bananas (seventh image).

There is no conventional portrait of Rochefort that survives. But it has been pointed out that, of the two figures in the center of the engraved titlepage (see detail, eighth image), the one on the right is a personification of what is sometimes called the “Colonial presence,” while the figure on the left is clearly a minister, and a Protestant one at that, since he is not wearing Catholic garb. Might this be Rochefort himself? It certainly seems possible.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.