Scientist of the Day - Charles H. Sternberg

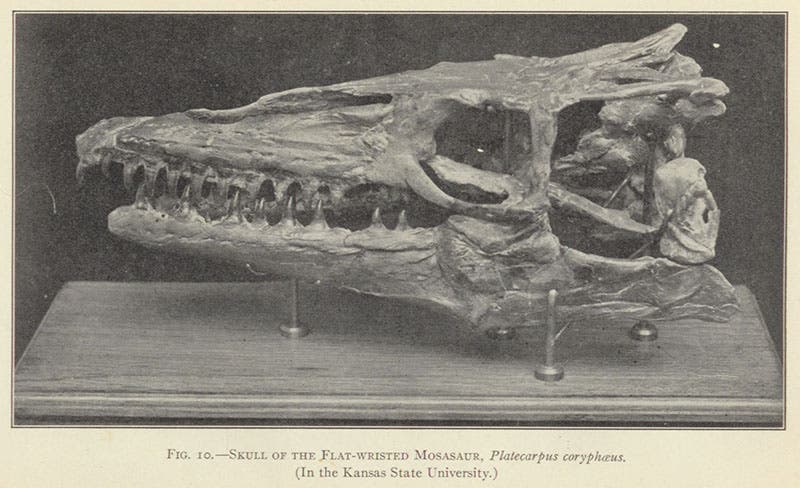

Skull of the flat-wristed mosasaur, Platecarpus coryphaeus, in The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Sternberg, 1909 (author’s collection)

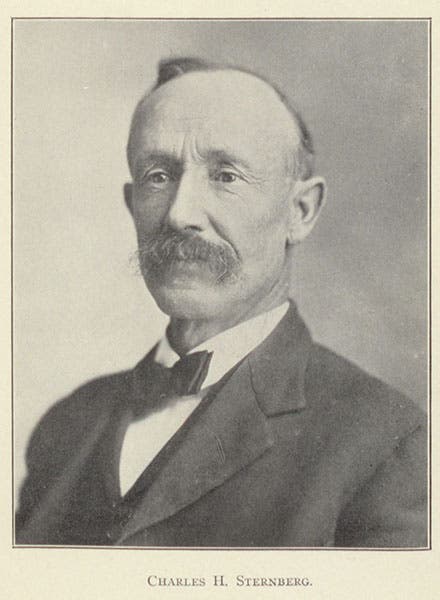

Charles Hazelius Sternberg, a Kansas fossil hunter, was born June 15, 1850, in New York State. He moved with his family to Ellsworth County, Kansas, when he was a teen, and he taught himself to find fossils in the Kansas chalk. Missing out of a chance to join Othniel C. Marsh on a fossil-hunting expedition to Wyoming, Sternberg wrote a letter to Marsh's rival, Edward D. Cope of Philadelphia, pleading for a job. Cope must have liked the fervor conveyed in the letter, for he sent Sternberg a draft for $300 and told him to go to work. Sternberg would hunt fossils for Cope for 8 years, before moving out on his own.

Portrait of Charles H. Sternberg, photograph frontispiece to The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Sternberg, 1909 (author’s collection)

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Sternberg, now aided in the field by his three sons, excavated dinosaurs, and they found many notable specimens, including the spectacular “trachodon mummy” with intact skin impressions that is still displayed in the American Museum of Natural History. We discussed some of his more notable dinosaur finds in an earlier post on Sternberg. Today, we are going to return to his days working for Cope, when many of his unearthings were not dinosaurs but Mesozoic marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, whose presence in Kansas rocks was made possible by the great inland ocean that covered Kansas during the Cretaceous period. Sternberg discussed the events surrounding his Kansas fossils in a book, Life of a Fossil Hunter (1909), a lovely copy of which I received as a gift from a colleague many years ago. It will one day migrate to the History of Science Collection at the Library. Most of our images today come from this book.

The gold-embossed spine of The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Sternberg, 1909, shown in lieu of the title page (author’s collection)

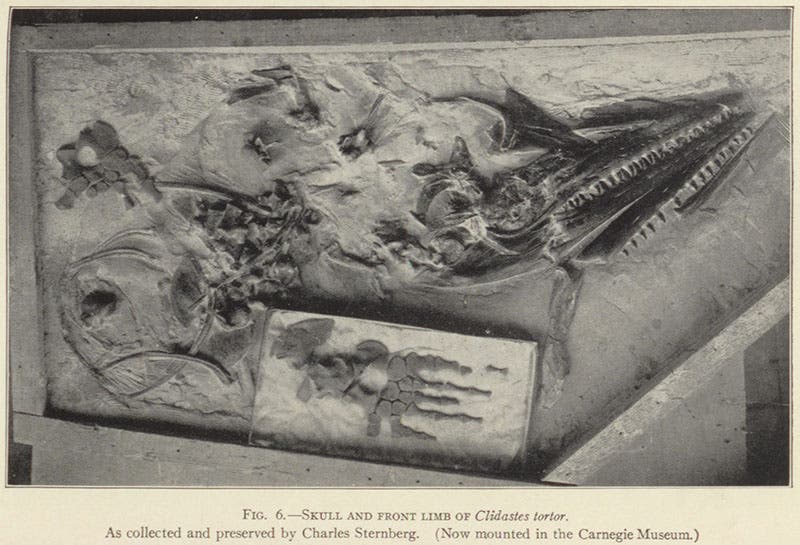

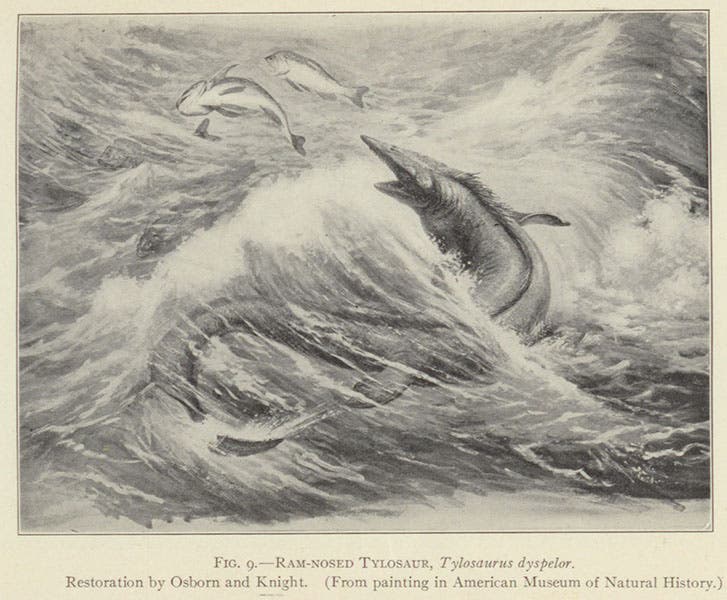

The Kansas chalk contains the remains of a variety of mosasaurs, which were swimming reptiles with crocodile-like jaws and bodies that could be 40 feet long. In truth, they came in a range of species and sizes, from the small Clidastes, 13 feet long, to Platecarpus, maybe 20 feet long, up to the large Tylosaurus, well over 40 feet in length. Sternberg located specimens of them all, many of them the most complete found up to that time. He and his son George developed ways of covering the better finds with plaster and then crating them up while still in the ground (in the beginning, before they learned about plaster of Paris, they used cooked rice from their stores). Often these boxed-up slabs weighed 600 pounds or more, but the two managed to haul them by wagon over the roadless plains to the nearest railroad depot and ship them off to Philadelphia, or later, to the highest bidder, which was often the University of Kansas in Lawrence, where Samuel Williston was professor of paleontology.

Skull and front limb of Clidastes tortor, found by Charles H. Sternberg and sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, in his The Life of a Fossil Hunter, 1909 (author’s collection)

One of many Charles Knight paintings reproduced in Sternberg’s book, courtesy of Henry F. Osborn and the American Museum of Natural History; this one depicts one of the large mosasaurs, Tylosaurus, specimens of which Sternberg recovered in the Kansas chalk, in The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Sternberg, 1909 (author’s collection)

Our first image shows a fine Platecarpus skull that ended up in what is now the University of Kansas Natural History Museum in Lawrence. A superb Clidastes skull, still in its matrix, was sold to the new Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh (fourth image). A Tylosaurus found by Charles and George, with the remains of a plesiosaur inside, ended up in the Smithsonian Institution; it was found after Life of a Fossil Hunter was written, so there is no image here. But Sternberg did include a dynamic painting of a Tylosaurus prowling the seas, executed by Charles Knight (fifth image). Sternberg was good friends was Henry F. Osborn, president and chief paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History. All of Cope’s specimens had gone to the AMNH after Cope’s death in 1897, which included many fossils found by Sternberg. So Osborn generously allowed Sternberg to reproduce many of Knight’s original paintings of dinosaurs in his book, although they are here in black and white, and, except for the Tylosaurus, are not really relevant to this book.

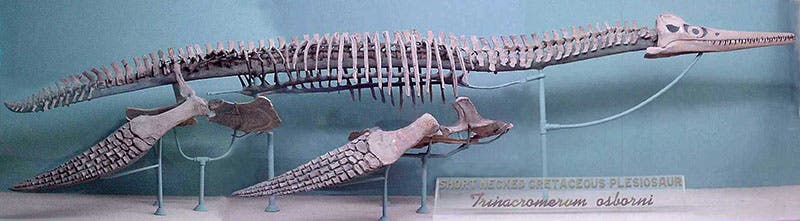

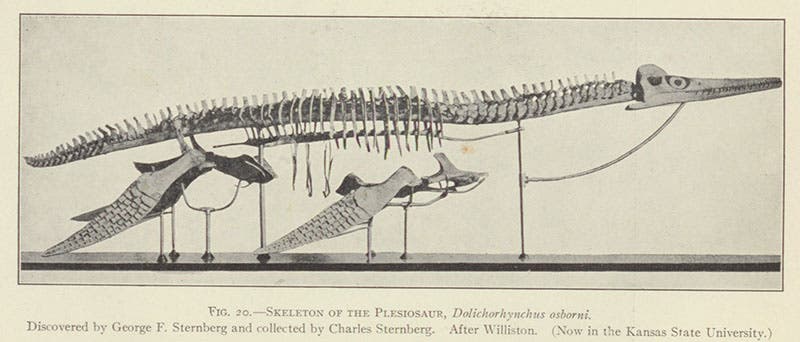

Mounted skeleton of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a short-necked plesiosaur found by son George Sternberg in 1901 and excavated by his father, on display in the museum at the University of Kansas, in The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Strnberg, 1909 (author’s collection)

Another common swimmer in the Cretaceous seas of Kansas was the plesiosaur. Sternberg found the remains of many of these, especially the short-necked species known as Dolichorhynchops. Son George came upon an especially complete specimen in 1901, Charles excavated it, and it was sold immediately to the University of Kansas, where they had it mounted. Sternberg photographed the mount for his book (sixth image); all of the bones are original except for the skull, which was deemed too fragile for display and was replaced by a reproduction. On a wonderful, old-school website, Oceans of Kansas, I found a recent photo of the mount, this time in color (seventh image). The mount has apparently stood the test of time.

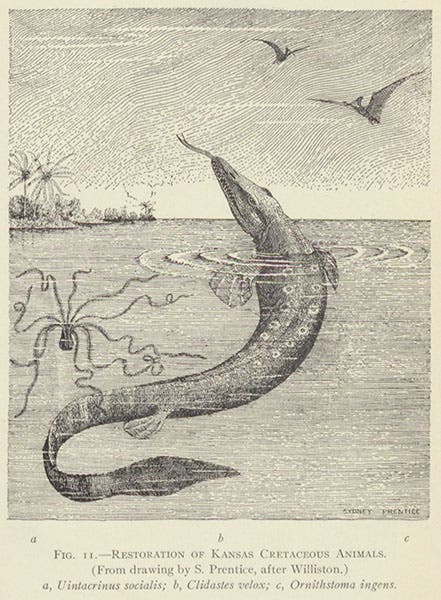

Another drawing reproduced by Sternberg introduced me to a new paleoartist (new to me, that is), Sidney Prentice. We show that illustration, which depicts three Mesozoic creatures, the center one being the mosasaur Clidastes (eighth image). Williston was writing the definitive monographs on mosasaurs and plesiosaurs in the 1890s and 1900s, and he found and employed Prentice in these and many of his later works. Prentice had a wonderful pen-and-ink technique that was quite different from that of most contemporary illustrators. He later went on to illustrate monographs on fossil whales. If I can find some of these, I will do a future post on Prentice with more examples of his work.

Restoration on paper of Clidastes velox, found by Charles H. Sternberg, described by Samuel Williston, pen-and-ink drawing by Sidney Prentice, in The Life of a Fossil Hunter, by Charles H. Sternberg, 1909 (author’s collection)

Specimens found by Charles Sternberg may be seen in most of the major natural history museums of the world. For those who live nearby, the closest venues would be the University of Kansas Natural History Museum in Lawrence and the Sternberg Museum in Hays, Kansas, which honors all the Sternbergs, but is actually named for son George, who taught at Fort Hays State and would carry his father’s legacy into the 1940s and 50s.

Charles Sternberg died on July 21, 1943, and is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto, where he had moved after his retirement. He was 93 years old.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.