Scientist of the Day - Charles Knight (publisher)

On Mar. 31, 1832, the first issue of The Penny Magazine moved from the presses to the stalls of the book vendors in London. This was a 16-page weekly newspaper, printed on both sides of one large sheet of paper and then folded into format. It was the brainchild of publisher and writer Charles Knight (1791-1873), working on behalf of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The periodical had many novel features: it was well-illustrated with woodcuts, covered a variety of topics, and was cheap, as the title tells us. The greatest novelty was the size of the circulation. I don't know how many copies of the first issue were printed, but within a short time, the circulation was up to 200,000, which was phenomenal for 1832. Five years earlier, it would have been physically impossible to print 200,000 copies of anything. Even the best presses could turn out only about 250 sheets an hour, which made a circulation of even 10,000 a difficult goal to hit. But in 1828, Augustus Applegath and Edward Cowper had supplied The Times of London with flat-bed presses capable of printing over 4000 sheets per hour, and suddenly, a mass-circulation periodical was possible.

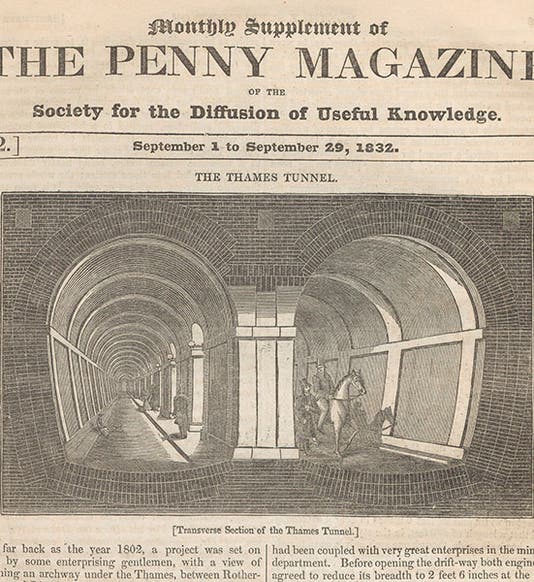

The Penny Magazine, issued every Saturday, was aimed at the working and lower-middle classes, hence the publication day, since the working class had no time for diversion during the workweek. Much of the text was written by Knight. The large number of illustrations was a necessity, since much of the intended audience could not read. Woodcuts were costly, so a large circulation for the magazine was a must, to pay the expenses of printing. Since it was not a daily but a weekly, it did not try to cover current events but instead sought to enlighten the audience as to what was going on in the world of literature, arts, entertainment, and science. Since our subject in this series is history of science, I selected a half-dozen pages from the first volume to illustrate the variety of scientific stories a reader might encounter in The Penny Magazine in 1832. Our opening image, showing the Thames Tunnel, was chosen because, well, it makes a great opening image, although in fact it was not from one of the weekly issues but from a monthly supplement that typically treated subjects in a little more depth. You can see that the woodcuts were not done on the cheap, but were of high quality, which no doubt added to the expense. The second image is page 1 of issue 1 of volume 1, important not for its images but for its position right at the front of the history of The Penny Magazine.

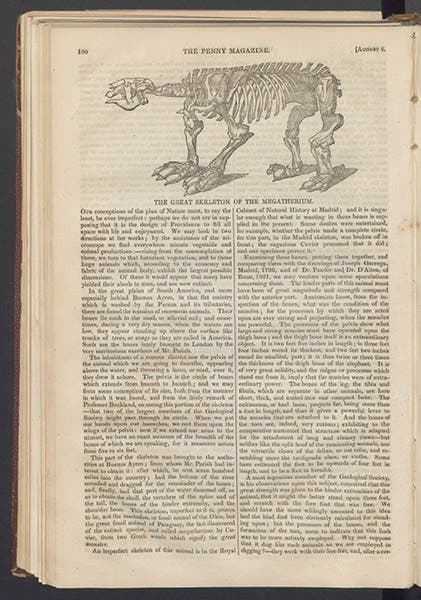

An example of how Knight attempted to bridge the gap between the world of scientists and the general public is the article on the Megatherium. A skeleton of this fossil ground sloth had first been described in 1796 (by Juan Bautista Bru de Ramon), and indeed the woodcut shows that very specimen. But in 1832, a paper was read to the Geological Society of London by Woodbine Parish, describing specimens of Megatherium that he had seen in Buenos Aires. Knight discussed Parish and his South American discoveries. and also explained to the reader just what Megatherium was and what kind of lifestyle it probably adopted, with its heavily clawed but clumsy hind feet.

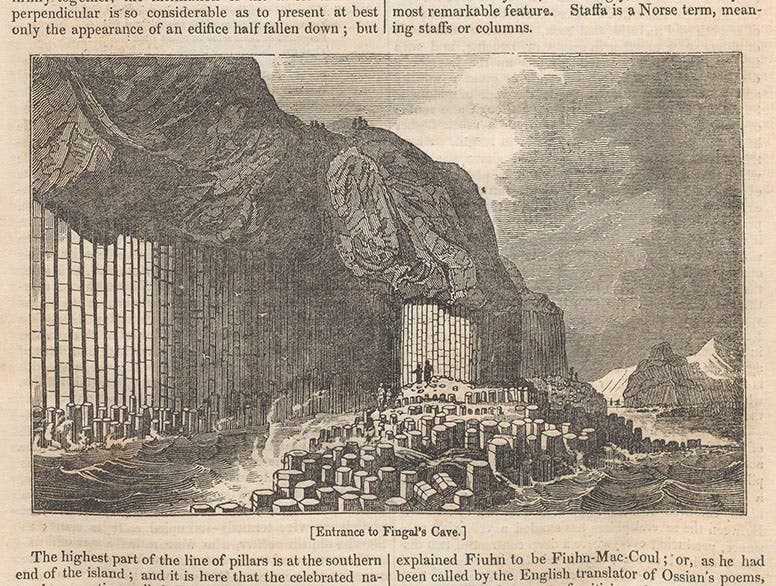

Another issue contained an article on Fingal's Cave, the basaltic wonderland on the isle of Staffa in the Hebrides. The woodcut is quite nice; we show it in a detail (fourth image). It was copied from one that appeared in a book by Thomas Pennant back in 1774, so it was not especially topical. But perhaps Knight knew that Felix Mendelssohn, inspired by his visit to Fingal's cave, had written an overture, called The Hebrides, or Fingal's Cave, which premiered in London on May 14, 1832.

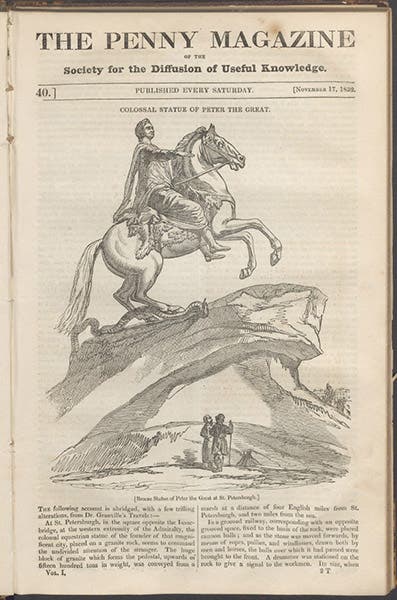

One article that surprised me was a front-page feature (issue no. 40) on the Bronze Horseman, the monumental statue of Peter the Great in St. Petersburg. Taking his account from a travel book, Knight told the story of how the great 1800-ton Thunder Stone, on which the statue sits, had been transported to St. Petersburg (we wrote a post once on Marin Carburi, who engineered the transport, in case you want to learn more about this classic feat of engineering). The statue was unveiled in 1782, so the surprise is why Knight thought this far-away sculpture and an account of the moving of the stone would be of interest to the average Londoner. Maybe just because it is a great story.

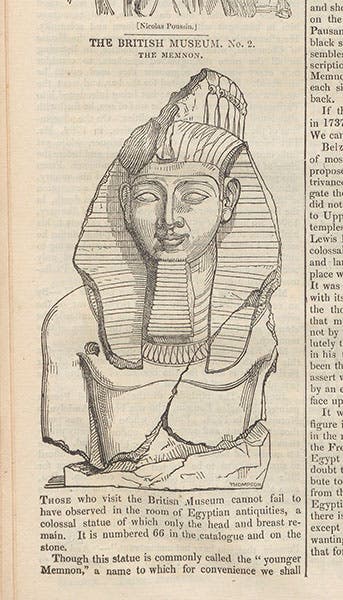

Our final selection is an article on what was then called the "Younger Memnon," a statue acquired from Egypt in 1817 by the British Museum and re-erected inside the Museum (where it still sits). In the text, Knight mostly discussed what the statue represented (not Memnon, says Knight) and how Giovanni Belzoni and Henry Salt collaborated to remove it from Egypt in 1816 and sell it to the Museum. You can learn more about the statue (and whether or not it inspired Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias) in our post on Belzoni.

There are many more examples of scientific and engineering topics treated by The Penny Magazine – a really surprising number, given the paucity of science-based stories in today’s newspapers. The Penny Magazine did well for a while, but the price had to be increased, which led to a slow erosion of subscribers, and the magazine published its last issue in 1845. We have the complete run in our serials collection.

Charles Knight did much more than issue The Penny Magazine; he published quite a number of popular works, including the works of Shakespeare (illustrated, of course), and we have in our collections one other work by him, The Pictorial Museum of Animated Nature (184-?), a two-volume folio set just filled with illustrations.

Knight lived to be 82, passing away in 1873. He was interred in the Old Burial Ground cemetery, Windsor. His name is almost always written as “Charles Knight (publisher)” in order to distinguish him from the slightly more famous (in this country) dinosaur illustrator, Charles Knight.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.