Scientist of the Day - Christian August Hausen

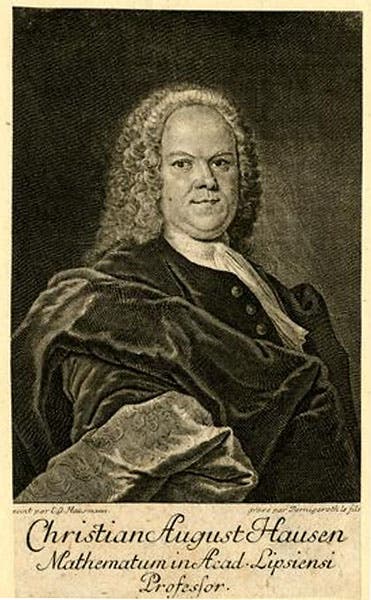

Christian August Hausen, a German mathematician and physicist, was born June 29, 1693. After studying at the University of Wittenberg, he joined the faculty at the University of Leipzig in 1714, and he would teach there for almost 30 years, until his death in 1743.

Sometime in the 1720s, Hausen travelled to London, where he met Edmund Halley, John Desaguliers, and Isaac Newton. He probably heard of Francis Hauskbee, a protege of Newton and one of the pioneer investigators of electricity, the first to build an electrostatic generator, consisting or a rotating glass globe. He died in 1713 and was succeeded by Desaguliers. Hausen encountered something in his visit that generated an interest in electricity, because he would dabble with electrical experimentation for the rest of his life. He almost certainly did not meet Stephen Gray, who was excluded from Newton's circle, and who around 1730 discovered electrical conduction, using "wires" of wet packthread that he strung for hundreds of feet around an English country estate house.

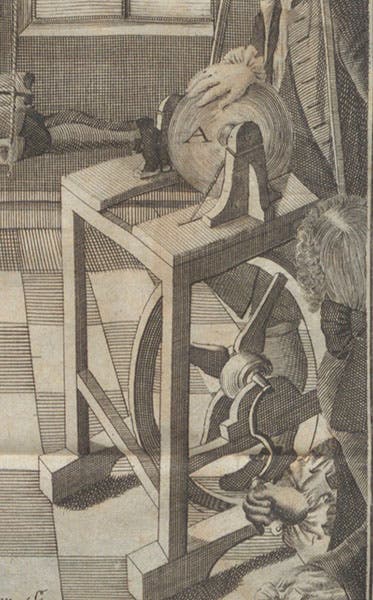

But later, back in Leipzig, perhaps in 1736 or 37, Hausen ran across Gray’s papers in the Philosophical Transactions, and he was fascinated. Gray described how he rubbed glass rods and held them up to his packthreads, and at the other end of the thread, bits of chaff would be repelled by the conducted electrical fluid. It was Hausen who put two and two together – why could we not repeat Gray's experiments, but instead of rubbing a glass rod, charge the threads instead with a Hauksbee electrical generator? The only impediment was a way to get the charge off the rotating glass sphere and onto the thread. Hausen took a metal gun barrel and suspended it from non-conducting silk cords, and charged the barrel with his machine. He called this his "prime conductor". The conducting threads were then run off the barrel in any direction you wanted. Prime conductors would become a staple of electrical investigations in the 1740s and 1750s. There is some controversy about who actually invented the prime conductor, as another German electrician Georg Bose, who knew and worked with the much older Hausen in Leipzig, also lays claim to the invention. When we do a post on Bose, we will consider the matter further.

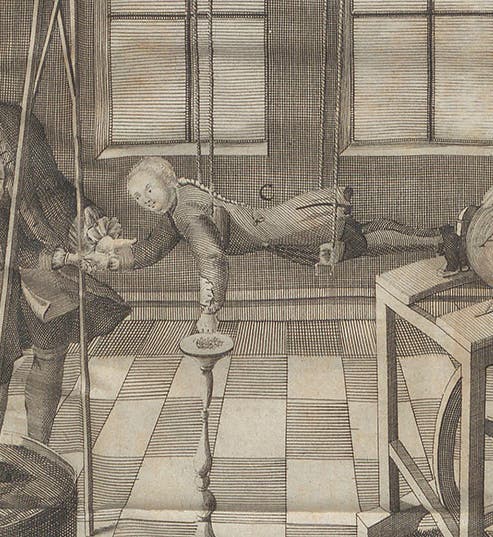

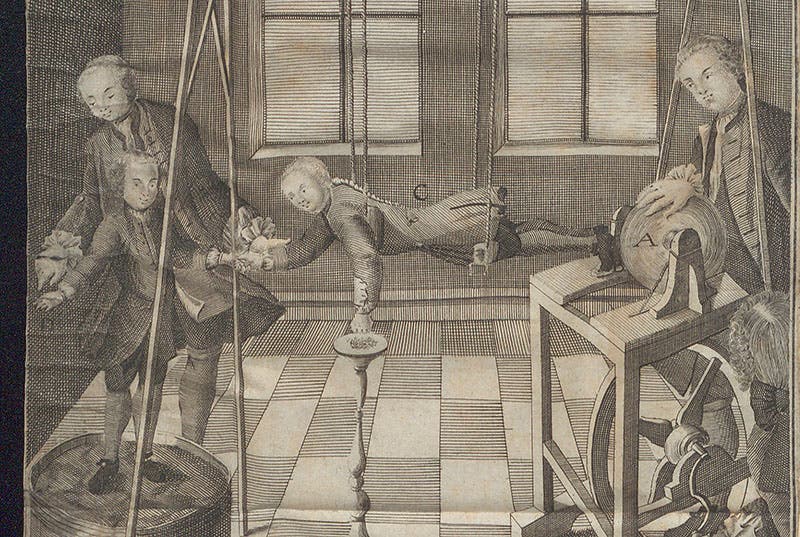

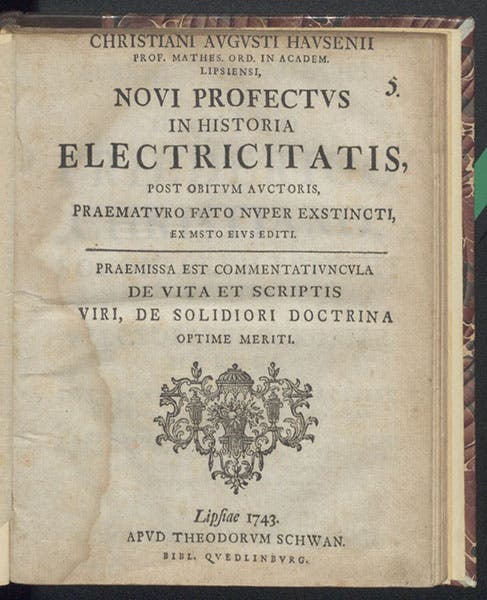

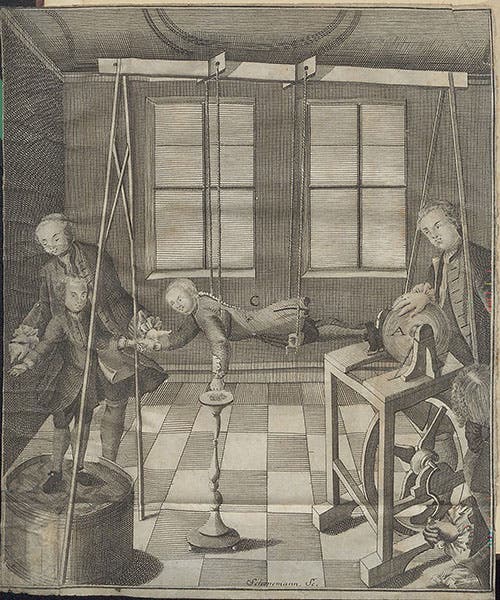

One thing we do know is that Hausen was the first to depict, on the frontispiece of his posthumous book, Novi profectus in historia electricitatis (1743), an experimental setup that would be much used in the next ten years for salon demonstrations of electrical effects. A young boy was suspended on strong silk cords from the ceiling. When his feet rubbed against a whirling electrical generator, one could draw sparks from his fingers, (or his lips, if one preferred), and his hair would stand on end. We show you the frontispiece of 1743 and several details. Hausen did not invent the boy-on-cords demonstration – he probably got the idea from Gray, who described it clearly in one of his papers. In fact, in our post on Gray, we showed the vey page where Gray described the sparking lad on cords. But Hausen provided the first illustration that I know of.

If you find yourself intrigued by electrical investigation in the 1740s, you might check our posts on Abbé Nollet, Johann Winkler, Georg Richmann, Jean Jallabert, Pieter van Musschenbroek, William Watson, and Benjamin Franklin. This decade provides a terrific example of how chaotic scientific investigation can be when there is not yet any guiding paradigm that suggests to scientists what they ought to be doing.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.