Scientist of the Day - Clifford Holland

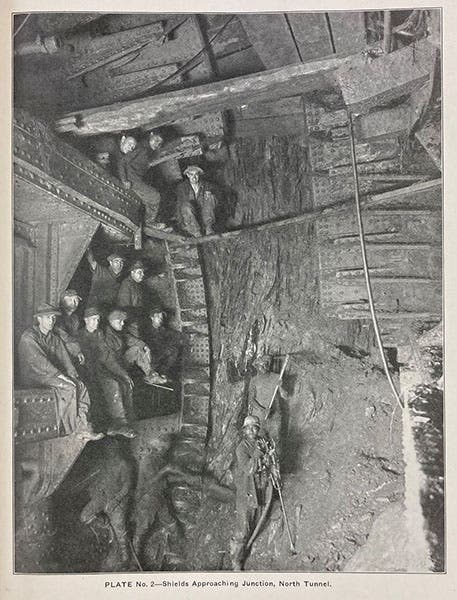

Clifford Milburn Holland, an American civil engineer, was born Mar. 13, 1883. Holland was the force behind the building of the first vehicular tunnel under the Hudson River between New York City and Jersey City, New Jersey. There had been several previous vehicle tunnels built beneath rivers, but the Hudson River tunnel would be far longer and go far deeper than any of these. Holland envisioned two iron tubes, each some thirty feet across, and each carrying two lanes of one-way traffic. The openings for the tubes were dug with a tunneling shield, essentially a moveable caisson, open at the leading end so the sandhogs could slowly dig their way forward. As the caisson/shield advanced, 30-inch-wide iron ring segments were bolted together and installed, one beyond the other, until each tube stretched some 9250 feet, 5,480 of which was under the river.

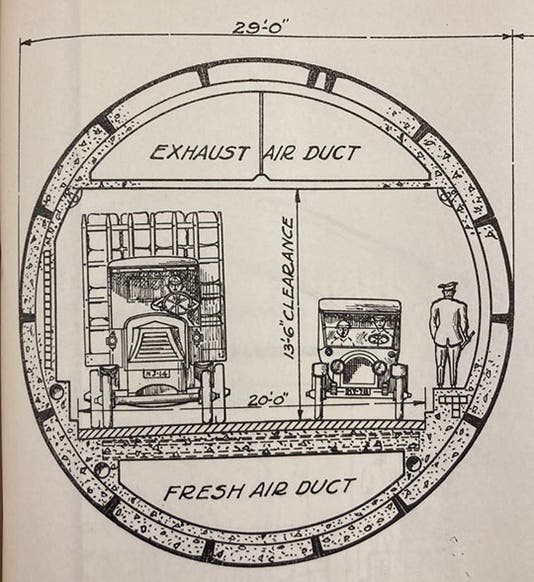

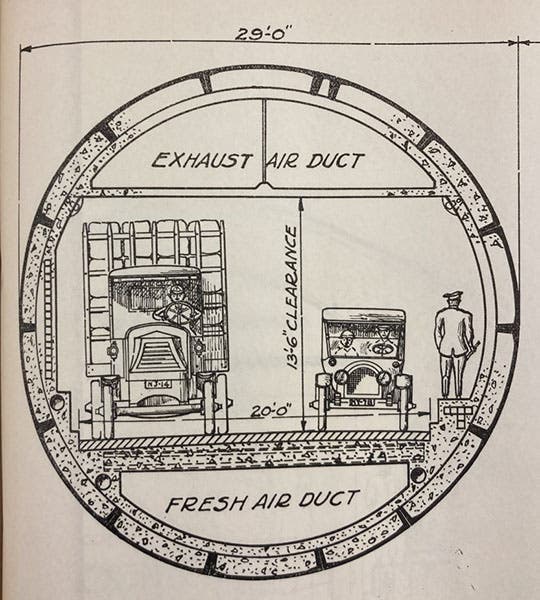

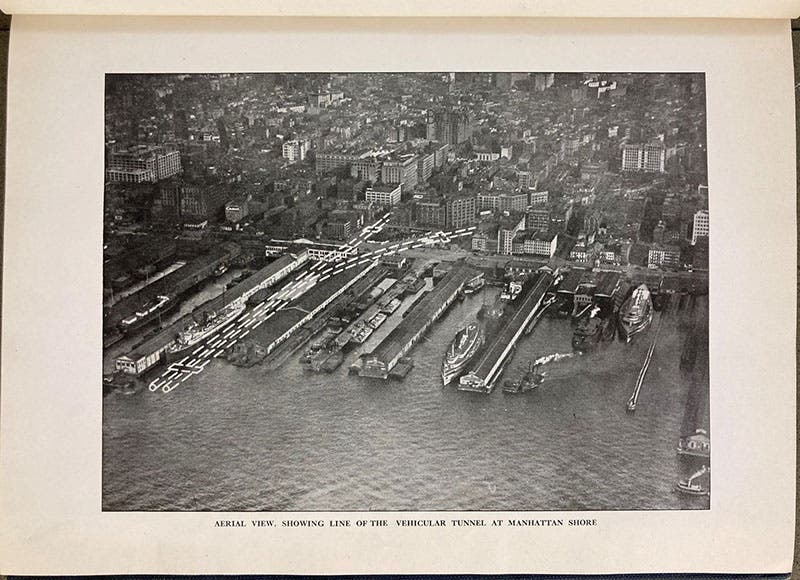

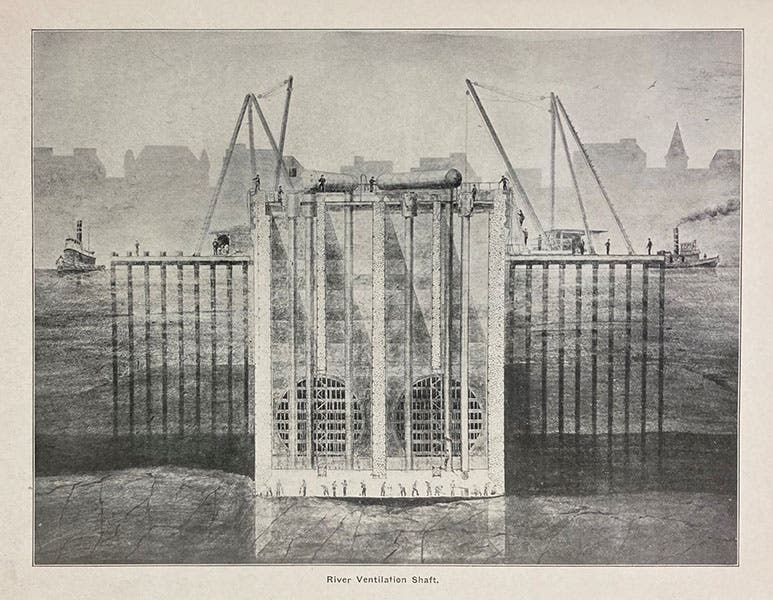

A major engineering problem was air circulation, since without it, no one had a prayer of surviving the fog of carbon monoxide that would fill the tubes. This problem Holland turned over to Ole Singstad, who ingeniously submitted a design to circulate air, not from end to end (which would require driving through a gale), but from top to bottom all along the tubes. In Holland’s diagram of 1919 (first image), you can see the air passageways above and below the roadbed. Pushing the air through the shafts required four massive ventilation towers, two on land and two in the river, with over 80 mammoth blowers, which could replace the entire air content of both tunnels in 90 seconds. We see a drawing from one of the Annual Reports that shows how one of the towers would look as it slowly rose from the river bottom (fourth image).

Since the tunnels were dug from each side of the river towards the center, another major problem was ensuring that they would meet in the middle. Just two days before the first tunnel was to be joined, Holland died of heart failure. Five long years of stress had done him in. When the first tunnel was completed two days later, the alignment of the two halves was off by just a fraction of an inch (fifth image). Two weeks after that, the Hudson River Vehicular Tunnel was renamed the Holland Tunnel.

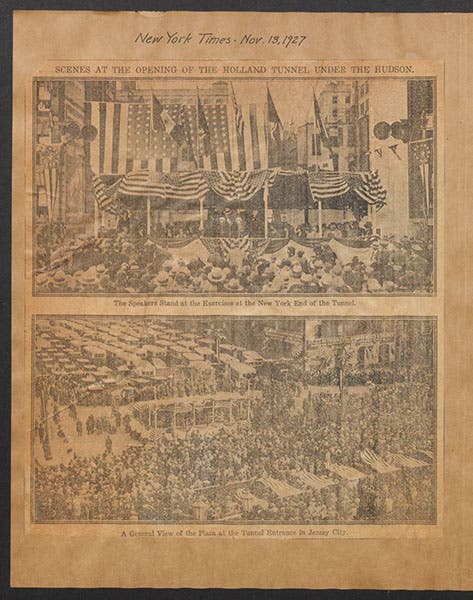

The Holland Tunnel opened to the public on Nov. 12, 1927, when President Coolidge used a telegraph key to unfurl American flags at both ends of the tunnel (the very same key that had been used by President Wilson in 1913 to blow up the Gamboa dike and complete the waterway for the Panama Canal).

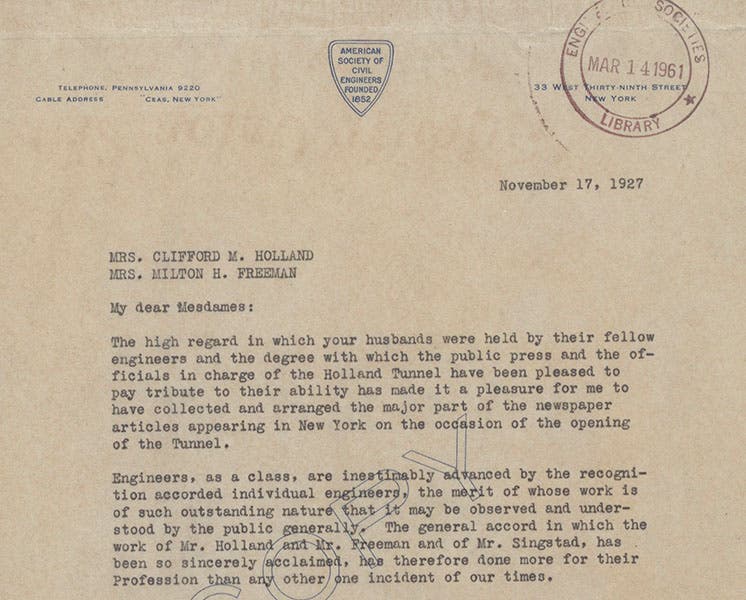

Not only did Holland predecease his tunnel, but so did his successor Milton Freeman, who died after only 5 months in harness. The tunnel was completed by Singstad two-and-a-half years later. At the opening, the widows of the two deceased chief engineers were feted and given the privilege of being in the first car to pass through the tunnel.

In further gratitude, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) made up a scrapbook for both Mrs. Holland and Mrs. Freeman, containing clippings from the New York papers for the period of Nov. 11-14, 1927. One was given to each woman, and a third copy was kept for the Society. I do not know what happened to the first two scrapbooks, but copy 3 is in our History of Science collection, coming to us through the acquisition of the ASCE Library in 1995. I read through the entire scrapbook while writing this notice, and I must say (since I don't do it often), it is great fun to write history from newspaper accounts. We recently had the scrapbook scanned, so you can flip through it yourself at this link. It is sobering to reflect on the fact that the clippings came from 11 different New York City newspapers, all in print and all in circulation in 1927. Only three of those are still alive and kicking, or perhaps just two, if you don’t count the New York Post.

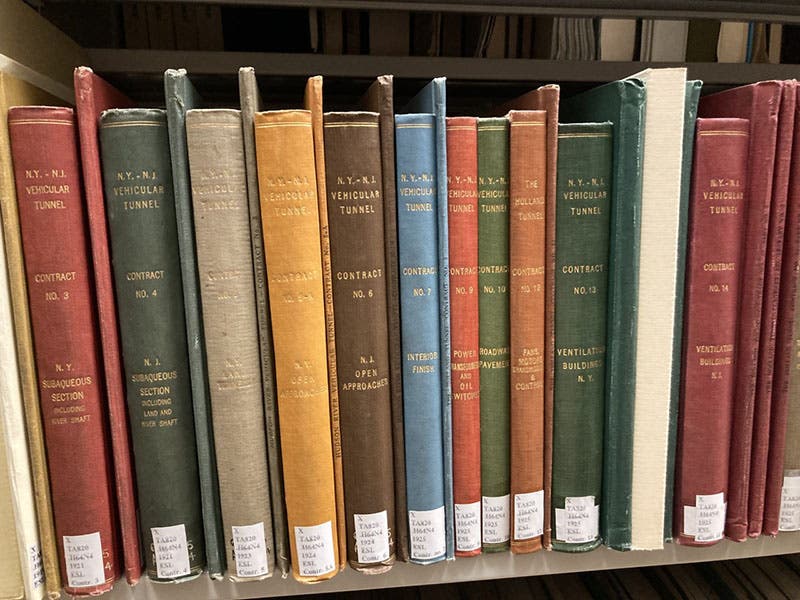

A portion (about one-fourth) of the Linda Hall Library’s collection of the Holland Tunnel bids and contracts (photo by the author)

We have in our collections, courtesy of the Engineering Societies Library, the Annual Reports of the Tunnel Commission from 1920 through 1926 (for some reason, the reports for 1927 and 1928 never came to us), and we have drawn three images from those Annual Reports for this post. We also have an apparently complete set of contract specifications and bids received, in some 35 bound volumes (ninth image). Our catalog record does not do justice to the richness of this set, which merits attention from historians of technology, as well as historians of Big Science.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.