Scientist of the Day - Colin Maclaurin

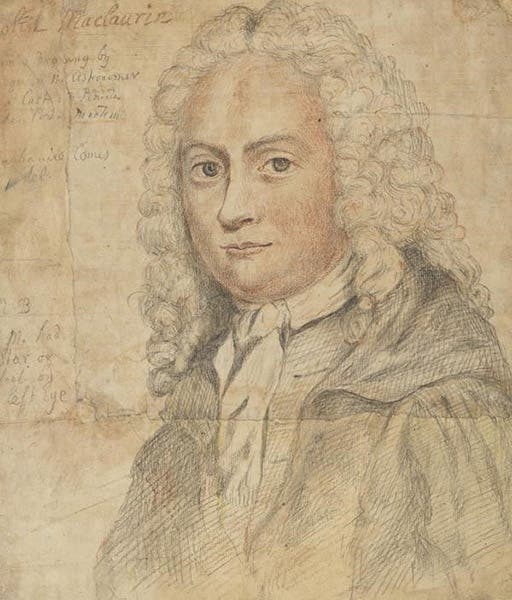

Colin Maclaurin, a Scottish mathematician, died June 14, 1746, at the age of 48. He was one of the most influential advocates for Newtonian physics and Newtonian calculus until his untimely death, and in the opinion of several historians, the greatest mathematician of 18th-century Scotland. His master’s thesis at the University of Glasgow, written when he was just 14, was a defense of Newton's theory of universal gravitation. He taught at Aberdeen for 8 years, travelling to London several times between terms to visit the Royal Society, where he met Isaac Newton, who was in his late 70s then and mellowing somewhat, with the death of his archenemy Gottfried Leibniz, and beginning to take an interest in promising young mathematicians. Newton apparently took a shine to young Maclaurin, saw to his admission to fellowship in the Royal Society (of which Newton was president), and recommended to the authorities at Edinburgh that Maclaurin be appointed to succeed to the professorship of mathematics there, when it became vacant in 1725. It is said that Newton even offered to supplement Maclaurin’s salary at Edinburgh, although it is not clear whether in fact he did so. But Maclaurin taught there until his death in 1746, and his tenure marked the beginning of what is usually called the Scottish Enlightenment, lasting from Maclaurin's time all the way through the end of the century. James Hutton is one of the markers of the end of the Scottish Enlightenment, and Hutton was a youthful pupil of Maclaurin at Edinburgh.

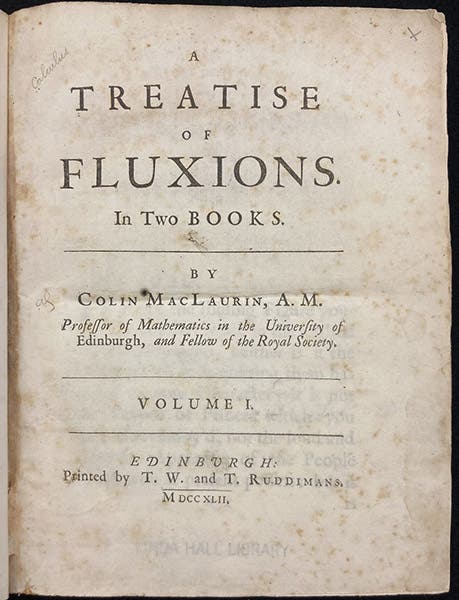

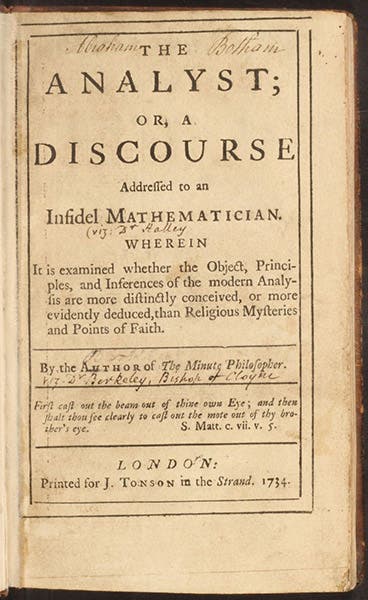

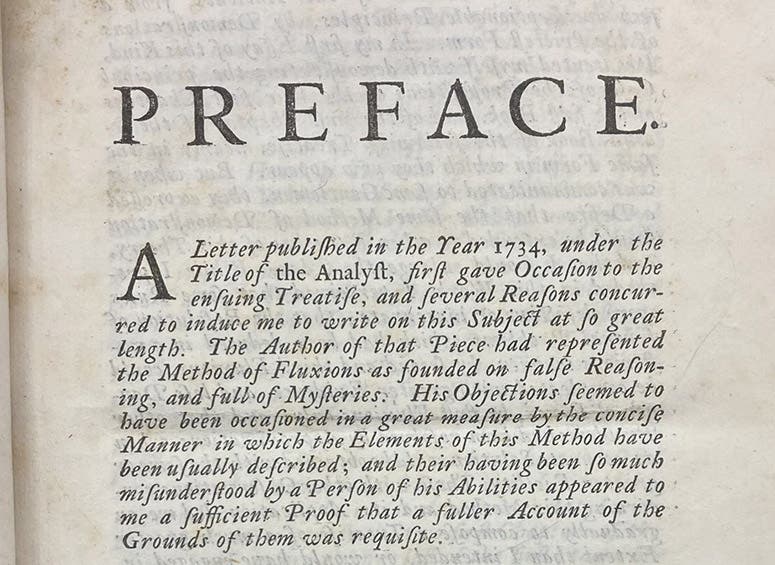

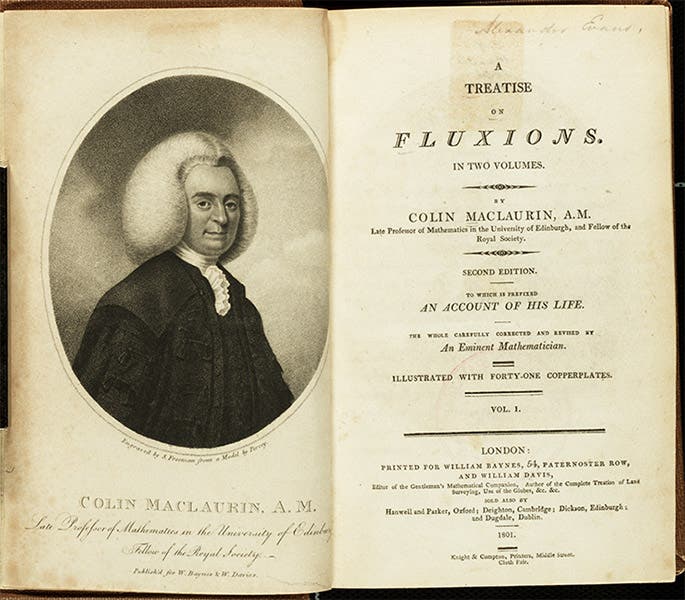

Maclaurin wrote two books that loom large in the history of 18th-century Newtonianism, both of which we have in our library. The first, A Treatise of Fluxions (1742), is a defense of differential calculus (second image). It was written in response to a book by George Berkeley, The Analyst (1734), which attacked Newtonian calculus (known as the method of fluxions) and the premise of infinitesimals. The full title of Berkeley’s book is revealing as to his objections: The Analyst; or, a Discourse Addressed to an Infidel Mathematician: Wherein it is examined whether the object, principles, and inferences of the modern analysis are more distinctly conceived, or more evidently deduced, than religious mysteries and points of faith. The “analysis” of the title is the method of fluxions, and the “Infidel Mathematician” is Edmond Halley, whose name has been written into our copy by a former owner (third image).

Maclaurin ably defended calculus and showed that it was not necessary to believe in the reality of infinitesimals for fluxions to be of use in analyzing the physical world. Maclaurin’s Fluxions was considered important enough to be reprinted almost 60 years later, in 1801, this time with an added "life of Maclaurin" and a frontispiece portrait, not a great one, with its bouffant wig, but the only printed portrait we have from that period. We own the 1801 edition, but our copy is missing the portrait, so we show the copy at the University of Pennsylvania Library (fifth image).

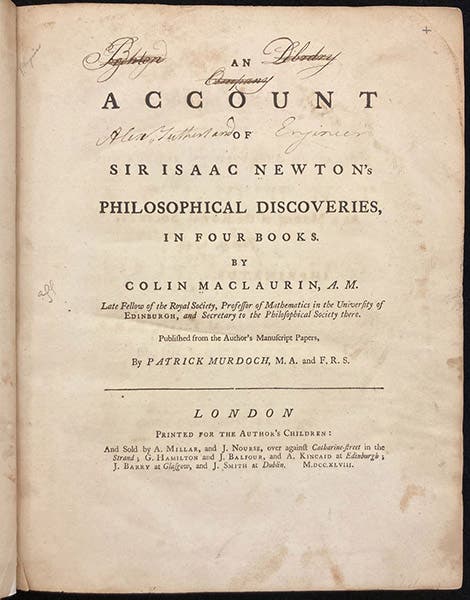

Maclaurin's other book, perhaps his most famous one, was a defense of Newtonian mechanics and Newton's universal gravitation. It was called: An Account of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophical Discoveries (1748; sixth image). Maclaurin worked on it for most of his short life – in many ways, it is just a rewriting and expansion of his master's thesis, informed by 30 years of acquired understanding. The final writing was interrupted by the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, in which Maclaurin was active in defending Edinburgh from the attacking army. He finally had to flee south to York, on which journey he fell from his horse and was exposed to the elements for some time. He made it back to Edinburgh, but he never recovered, and died on this day in 1746.

Maclaurin's Newtonianism is notable because it was embedded in a deep natural theology, different from Newton's, but one of which Newton probably would have approved. Maclaurin believed that the clockwork universe revealed by Newton was a sign of Divine Providence and profound evidence of the Wisdom of God in creating such an intricate operating cosmos. Indeed, for Maclaurin, as perhaps for Newton, universal gravitation was not a mechanical force, but the direct result of God’s manifestation in the world. It is interesting that the other prominent figure in the early Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume, was also an ardent Newtonian, but saw things quite differently when it came to natural theology. You can read more about Hume's attack on natural religion in our post on Hume.

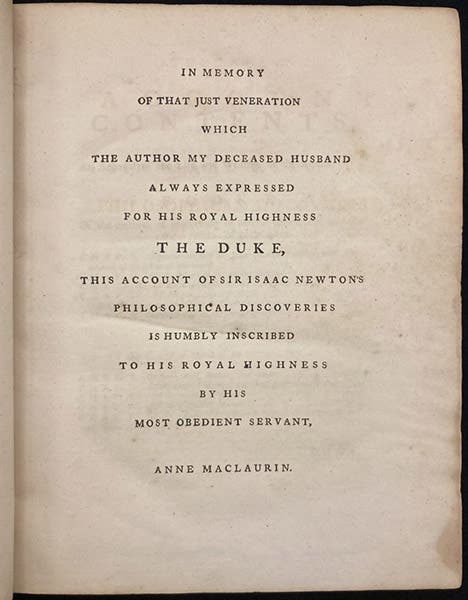

Maclaurin was dying when he dictated the final passages of An Account of Newton's Philosophical Discoveries. The manuscript was readied for publication by Patrick Murdoch of the Royal Society. The dedication to the Duke of Argyll was written by Maclaurin’s surviving wife, Anne, who must have been well-respected by the Duke, or this would never have been permitted (seventh image).

Maclaurin was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh, where there is a memorial plaque (eighth image). If you visit, look for markers for Joseph Black and James Hutton, both of whom would later be interred there.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.