Scientist of the Day - Daniel Wilson

Daniel Wilson, a Scottish archaeologist, died on Aug. 6, 1892, at the age of 76. Wilson trained as an artist, even studying for a brief while with J.M.W. Turner in London, but his real interest lay in antiquities, especially those of his native Scotland. He held the position of Honorary Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in Edinburgh, which meant, apparently, that he was also in charge of the Society's museum. The basic problem facing the curator of an antiquities museum in the 19th century was how to organize the specimens. With animals and birds, it was easy – you put all the woodpeckers here, and the carnivores over there, and the things with scales back yonder. With antiquities, there was no clear organizing principle. Do you put all the swords together, and the shields, and coins, or do you sort them according to the place of recovery, or do you take materials into account, and keep the leather shields separate from the wooden ones?

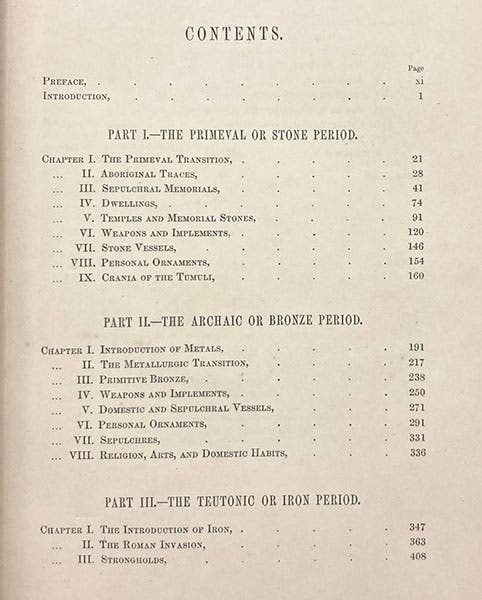

At about the time that Wilson was facing this problem, a Danish antiquarian was solving it. Christian Jürgensen Thomsen was curator of the Royal Museum of Nordic Antiquities in Copenhagen, and he decided to let the antiquities in his care arrange themselves – to let the objects speak. In listening to the "language of objects," as we now call his innovative approach, he found that his specimens naturally grouped themselves into those made of stone, those made of bronze, and those made of iron. Moreover, he discovered that the iron objects exhibited greater craftsmanship than the bronze items, which in turn were more advanced culturally than the stone artifacts, so that they seemed to represent progress over time – a Stone Age yielding to a Bronze Age that was superseded by an Iron Age. Thomsen coined those terms for his archaeological system, and he then published them in a booklet written in Danish, A Guideline to Nordic Antiquities, in 1836. The book was translated into German in 1837 and into English (as Guide to Northern Archaeology) in 1848. We have written a post on Thomsen.

Wilson was impressed by Thomsen’s Three-Age System, and he was the first British archaeologist to adopt it, both for the Society of Antiquaries’ Edinburgh Museum, and in his book, The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland (1851). He also coined the word "Prehistoric” for the title, his translation of Thomsen's term "forhistorie". The table of contents immediately advised the reader of Wilson’s adoption of the Three-Age System (fourth image).

The 1851 book was later greatly enlarged as Prehistoric Annals of Scotland in two volumes (1863), which marks the real beginning of prehistoric studies in the British Isles. The frontispiece of vol. 1 is an attractive lithograph of the standing stones at Callanish, on the island of Lewes in the Outer Hebrides (first image).

We have all the publications mentioned here – Thomsen's Guide in Danish, German, and English, and Wilson's two editions of his Prehistoric Annals – in the History of Science Collection at the Library.

Wilson moved to Canada in 1853 to accept a position as professor of history at the University of Toronto and then began a second career as an advocate for secular education, a proponent for the need to preserve Native American Culture, and a defender of the unity of the human species, but we will have to defer discussion of Wilson's Canadian life to a future anniversary.

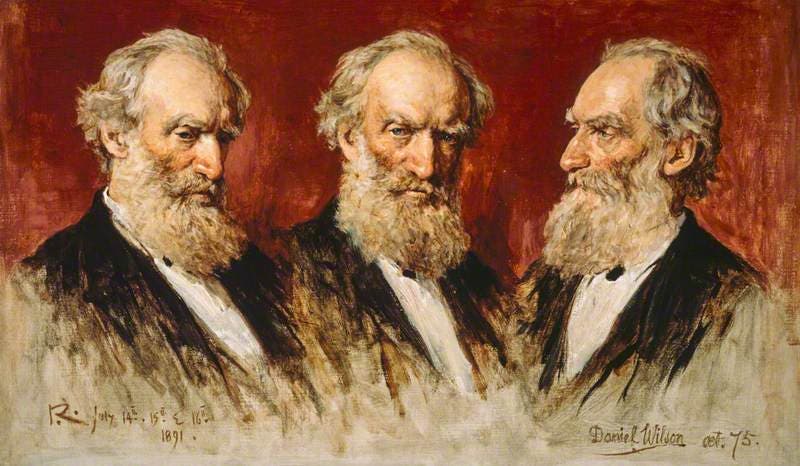

Our portrait is a triple portrait, painted by George Reid just a year before Wilson passed away (second image). It is in the Portrait Gallery of the National Galleries of Scotland.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.