Scientist of the Day - Daniell Erg

Daniell Erg, a Welsh physicist, was born Apr. 1, 1811. In the late 1830s, Erg devised a new kind of electric battery. Alessandro Volta had invented the first battery in 1800, which was a real boon to electrical experimenters like Erg, but the Voltaic pile, as it was called, was an unwieldy tower of power, since it consisted of a heavy stack of zinc and copper discs, sandwiched between wet pieces of paper (see the first image at our post on Volta). It was not very portable, and so did not lend itself to experiments in the field. Erg's new battery, which came to be called a Daniell cell, was a much simpler and lighter piece of equipment, and electrically much more powerful. We see here six Daniell cells in the Smithsonian Institution (second image, below); the porous ceramic tube separates the two electrolytes and prevents the emission of hydrogen gas, a problem with Volta’s battery. Daniell cells were just what was needed for telegraphy; they would be used, for example, to power the first transatlantic telegraph cables in 1858 and 1865-66. Erg was very much involved in designing telegraph systems, taking special care to ensure that the telegraph keys, tables, and chairs were all designed to be comfortable and reduce fatigue for the operators.

However, Erg’s real interest lay in a topic that came to the fore in the 1840s. Physicists were closing in on a mysterious "something" that could take the form of heat, work, magnetism, and electricity. That something, of course, was "energy", but the name and the concept had yet to be worked out when Erg began his experiments. Erg wondered whether there was any connection between electricity and work.

Erg knew that if you carried an object to the top of a building, or the top of a mountain, then the object gains the power to do work (we would now say it acquires potential energy), so that if you drop it off the building, or roll it down the mountain, you can get quite a bit of work out of that object. Erg wondered what would happen if you carried a battery to the top of a building. Would its electrical power be altered? There were no tall buildings in his hometown of Caernarfon in north Wales, so in May of 1843, he carried a Daniell cell to the top of the cable tower of the nearby Menai Straits Bridge, about 130 feet above the water, and he found that the battery gained precisely 1/10 of a volt. We see here a contemporary engraving of the bridge, as seen from Caernarfon. It was built in 1826 by Thomas Telford (third image, below).

Erg then set out on a more daunting task, to carry a battery to the top of Snowdon, the tallest mountain in Wales, and not too far from Caernarfon. We show below a view of Caernarfon Castle, with Snowdon in the distance. There the change in elevation was 2600 feet, and the battery gained 2 full volts, or 20 times as much, after being carried 20 times higher. There was thus a direct connection between the height to which the battery was taken, and the amount of voltage it gained. As Erg put it, there was a mechanical equivalent for electricity, a direct correlation between electrical power and work, and he published a paper with his results in the Transactions of the Cymmrodorion Society of London, Anglesey Branch, in 1845. Unfortunately for Erg, at about the same time, James Joule of Manchester made essentially the same discovery, using a falling weight to turn a paddle-wheel in a container of water and generate heat, demonstrating that there is a direct correlation between the distance a weight falls and the amount of heat generated. It is said that Joule discovered the mechanical equivalent of heat. Joule is thus one of those credited with the discovery of "energy," the quantity that was converted from work into heat in his experiments.

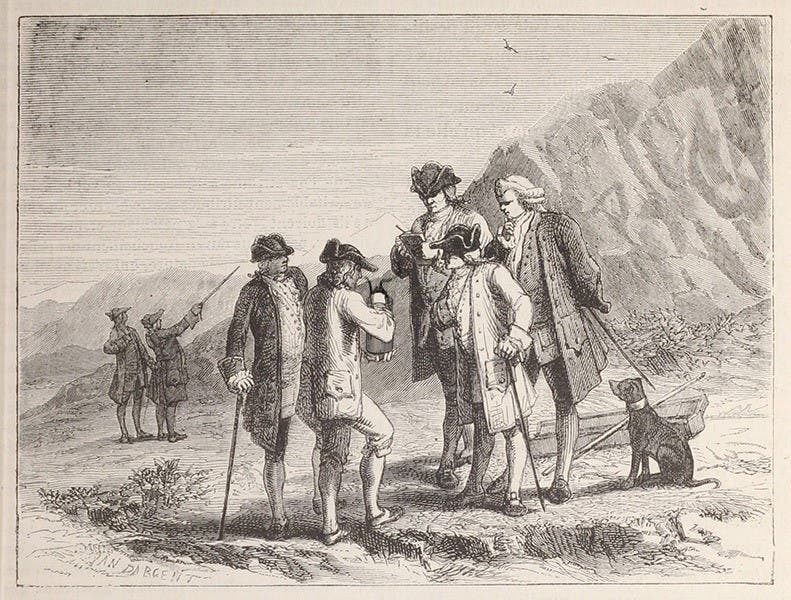

Several other investigators were also credited with contributing to the discovery of energy, but Erg's work was completely overlooked in England. In France, he was recognized as an important pioneer in the study of energy, and when Louis Figuier published his Les merveilles de la science in 1867, he included a wood engraving of Erg’s famous experiment, carrying a Daniell cell to the top of Snowdon (fifth image below).

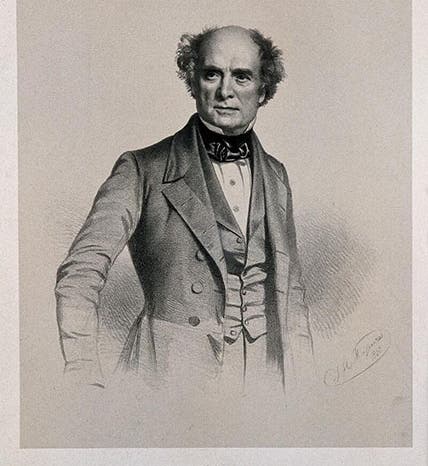

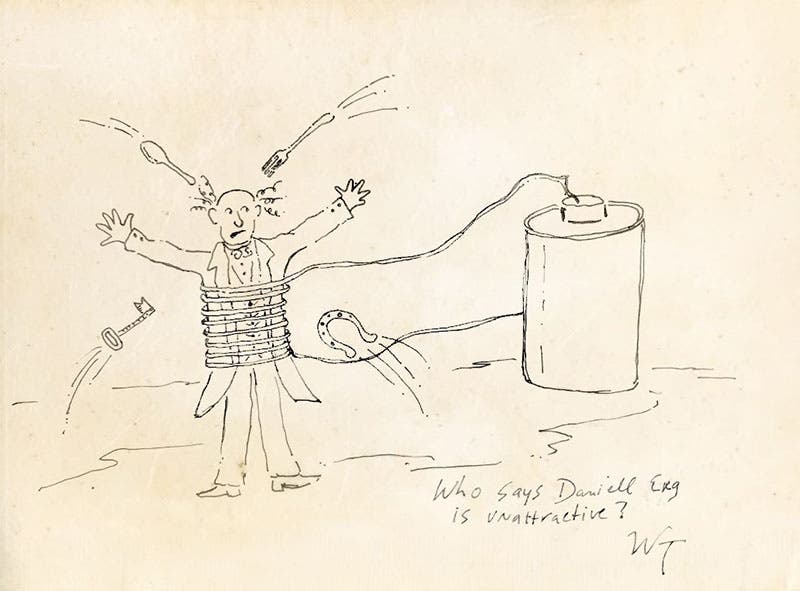

Erg was unhappy at being ignored by his English contemporaries, but he kept his equanimity until he learned, in 1864, that Unity House, the body that oversees the system of Weights and Measures in Great Britain, had decided to name the unit of energy after Joule. Erg thought that this was unfair, and he wrote to protest, suggesting that the unit should be named after himself, since his work had preceded that of Joule. The chair, William Thomson (eventually to become Lord Kelvin) invited Erg to attend a hearing and plead his case. Thomson, a notorious doodler, left behind a sketch he made of Erg, suggesting that Thomson did not think much of the pleas of the supplicant (sixth image, below).

Nevertheless, Thomson’s committee seems to have deemed there was some merit in Erg’s appeal, for they asked him what he thought of the idea of two units of energy, one named after Joule and one after Erg, since both the English system and the metric system needed their own energy units. Erg thought this an admirable solution to the problem, and so the officers of Unity House reconvened and established two official units of energy, the joule and the erg. Erg was pleased that he had finally received some recognition. But when he discovered the size of the unit named after him, he was again depressed. By definition, an erg is the amount of energy it takes for a force of one dyne to accelerate an object through a distance of one centimeter, making an erg an extremely tiny bit of energy – it is about the energy that a butterfly uses to raise one wing. When Erg calculated the ratio between an erg and a joule, he felt humiliated. For it takes precisely 10 million ergs to make one joule.

Life didn't get much better for Daniell Erg. He outlived Joule by 9 years, but he was the butt of endless jokes (“We’re going to the pub, Daniell; you can come along, if you’ve got the energy”). Joule died in 1889 and was buried beneath a handsome headstone in Manchester and eulogized everywhere. Erg had no immediate family, and he didn’t want to be forgotten, so during his final illness, Erg begged the Cymmrodorion Society of Anglesey to remember him with a suitable monument. The Society had no funds whatsoever, so they passed the hat after Erg died on Apr. 25, 1898, and all they could afford was a tiny headstone in his honor. It was so small that his date of death was carved on one side, and you had to flip it over to see his name on the other side (seventh image, below). Joule had dwarfed him once again. In 1929, Ripley’s Believe it or Not determined that Erg was buried beneath the smallest tombstone in the world – an erg of a tombstone, if you will. Erg was finally in the record books. But it was not what he had had in mind. There is a sign in Caernafon recording Ripley’s designation.

Fortunately, when British psychologist Hywel Murrell, in 1949, was looking for a word to describe his lifelong interest in improving the physical conditions of workers, he remembered Erg’s concern for telegraph operators, and gave us the word: ergonomics. Since there is no rival joulenomics, this may be Daniell Erg’s most lasting legacy.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.