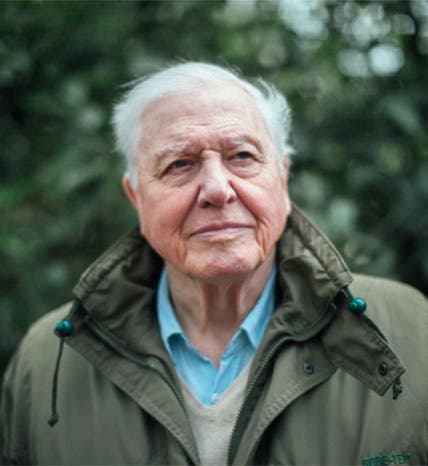

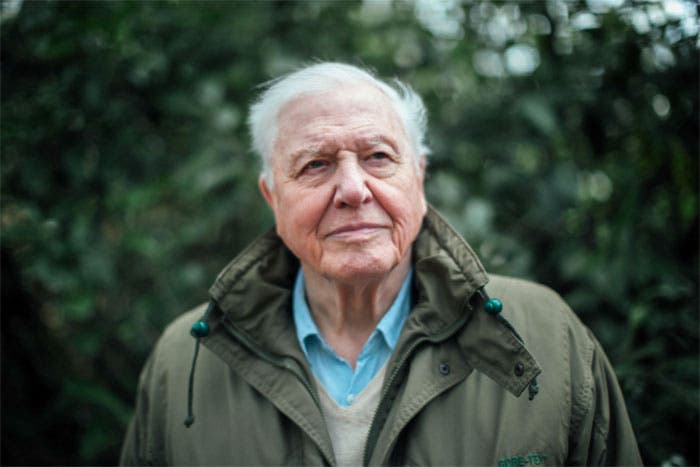

Scientist of the Day - David Attenborough

David Attenborough, an English broadcast executive and naturalist, was born May 8, 1926, and is still very much alive. Before he became famous as a wildlife filmmaker and presenter, Attenborough was head of programming for BBC 2, and it was Attenborough who commissioned Kenneth Clark's Civilisation series in 1969, the first series to go on location around the world with a leading expert who wrote and delivered his own commentary. It was also the first such series of programs to be filmed in color. It was such a success that Attenborough commissioned another series, this time on science rather than art, and the result was Jacob Bronowski's Ascent of Man, which first aired in 1973, 50 years ago, and it is still, in my opinion, the best series on the history and philosophy of science ever broadcast. With two such spectacular successes as a programmer, Attenborough then took to the field and showed that he could be a star in his own right. He did nine series of almost 80 wildlife programs for the BBC, with topics such as Life on Earth (1979), The Living Planet (1984), The Life of Birds (1998), and The Life of Mammals (2002).

The photography for these programs was provided by the BBC Natural History Unit, which became more and more expert with each series. But the charm of these shows was not just the photography – which could be pretty spectacular – but Attenborough's scripts, which he wrote, and his narrative style, which was intimate and cleverly teasing, and delivered in a hush-hush, manner, as if the events were occurring just five feet away (which, in some cases, they were). He included many "two-shots," where the animal or plant under observation and Attenborough were seen in the same frame, often interacting. Here is an example, a clip from The Life of Mammals showing Attenborough conversing with a sloth, where you can get a pretty good idea of the Attenborough style of presentation.

Probably the most famous of all the Attenborough segments is one that he did for The Life of Birds in 1998, on the lyrebird. This one builds to an unexpected climax, which Attenborough draws you into innocently but inexorably.

As Attenborough’s popularity as an involved observer of Nature grew, the BBC commissioned much more lavish productions from the Natural History Unit, such as Blue Planet (2001), Planet Earth (2006), and their successors, Planet Earth II (2016) and Blue Planet II (2017). For these, Attenborough no longer wrote the scripts, but was the presenter and narrator. Yet he managed to make the scripts his own, with his inimitable sense of timing, and his low-key manner.

There are many segments from these later series on YouTube, made available by BBC Earth (which has almost 12 million YouTube subscribers, giving you an idea of Attenborough's popularity). I screened quite a few for this post, and, eliminating those you would not want to watch while eating breakfast, chose these two for your further viewing pleasure: the Australian land-crawling octopus, and the Portuguese man o' war, for both of which Attenborough, understandably, has no on-screen presence, except for his voice, which belies that statement, since it is an unmistakable presence. You can find many more Attenborough treasures online – just enter "David Attenborough" and your animal or environment of choice in the search box.

Attenborough's programs for the first 25 years were not especially environmentally conscious – that was not their function, in his opinion. He didn't even become convinced of human involvement in climate change until 2004, for which he has taken some criticism. But ever since (in his 80s and 90s), he has become thoroughly committed to the dire task of warning what will happen to Planet Earth if humans do not quickly mend their ways.

For me, Attenborough represents a broadcasting lesson to which no one seems to be paying any attention: that a presenter is much more effective when he or she has intimate knowledge of the material being presented. That is why Kenneth Clark, Jacob Bronowski , Carl Sagan, and Attenborough were and are so compelling – they are believable. I love Alan Alda as an actor, but he had no business hosting Scientific American Frontiers for all those years, nor did Liam Neeson have any credibility narrating a series on Evolution, nor does any other celebrity reading a script about someone else's area of expertise. Where, oh where, is the next David Attenborough going to come from, if we give those jobs to celebrities and actors?

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.