Scientist of the Day - David Edward Hughes

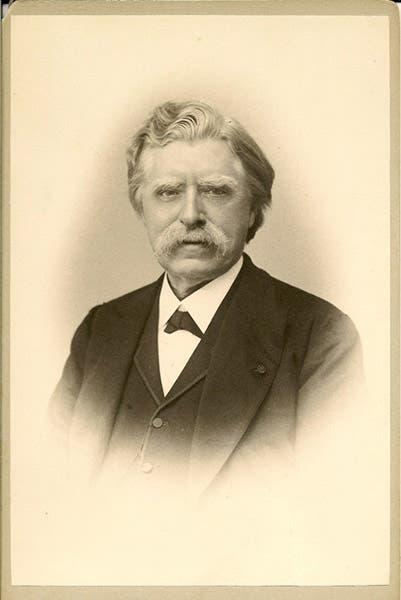

David Edward Hughes, an English-American physicist and musician, was born May 16, 1831, probably in London. He had considerable musical talent as a child, and when his parents moved to the United States, he pursued musical studies, and managed to land a position as a professor of music at a small college in Kentucky.

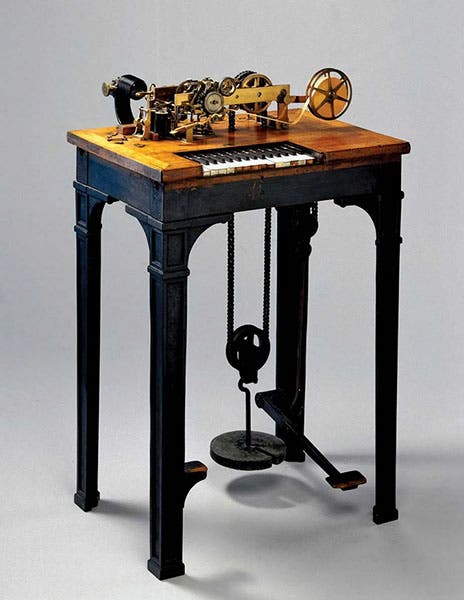

But Hughes was also a tinkerer and inventor, and as soon as the telegraph began to spread across the U.S., Hughes set out to make a better transmitter and receiver. He ended up inventing, in 1855, a receiver that recorded the incoming signal on a paper tape. About this time, he moved back to England to market his device, at which he was quite successful. There are various Hughes paper-tape telegraph receivers to be seen in technology museums, such as the Science Museum in London (third image). I like the piano-style keyboard. We should let musicians design more of our electronic devices.

Hughes then turned to microphones, which could convert sound waves into electrical impulses, necessary for the invention of the telephone. Hughe’s microphones utilized carbon in some form, which was very sensitive to tiny disturbances. Several people invented carbon microphones at about the same time, and Thomas Edison was awarded the patent in 1877, but Hughes preceded him and is usually credited with the invention.

In 1879, Hughes noticed that his microphones sometimes detected sparking from some of his experimental equipment, even when there was no sound. To determine how far these disturbances could travel, he built a clockwork device, called an interruptor, that would automatically break a circuit, while he walked away with his microphone. He found that the microphone could detect the circuit interruptions up to 1500 feet away from his lab.

Hughes, it would seem, had discovered electromagnetic waves, some 9 years before Heinrich Hertz more famously generated and detected such waves. Hughes thought something unusual was going on, that perhaps some sort of wave other than sound was being generated, so in 1880, he invited over a few experts from the Royal Society of London. to witness a demonstration. There were some smart men on this committee, including Thomas Huxley and George Stokes, and probably William Crookes, but they did not realize that something unexpected was taking place. Stokes, the physicist, thought the phenomenon being demonstrated was a form of electromagnetic induction, where a changing magnetic field induces a current in a wire that intersects the magnetic field. Electromagnetic induction was reasonably well understood, and Hughes was convinced by Stokes that nothing unusual was occurring, and he let the matter drop. It wasn’t until 1892, after Hertz’s discovery was announced, that William Crookes recalled Hughes’ demonstration, and he and others began to realize that Hughes had probably been the first to discover radio waves.

Guglielmo Marconi gave his first public demonstration of wireless telegraphy, or radio, on July 27, 1896, and Hughes gave both Hertz and Marconi full credit for their work, and never made a fuss about his early experiments being overlooked. He died on Jan. 22, 1900. Twenty-two years later, the pieces of equipment he used for his Royal Society demonstration – a carbon microphone, a battery, and the interruptor – were discovered in a London flat. The discovery warranted a notice and a photograph in Popular Science Monthly (August 1922 issue; fourth image), and the equipment, its historic significance now appreciated, was transferred to the Science Museum in London, where the clockwork interruptor, at least, is on display (first image).

There is a blue plaque honoring Hughes’ invention of the microphone outside his former home on Great Portland Street in Westminster (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.