Scientist of the Day - Davies Gilbert

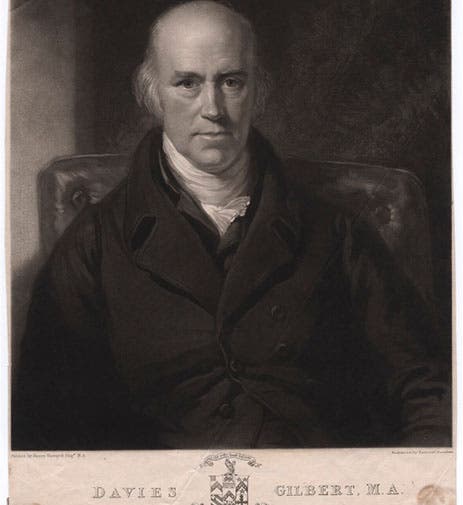

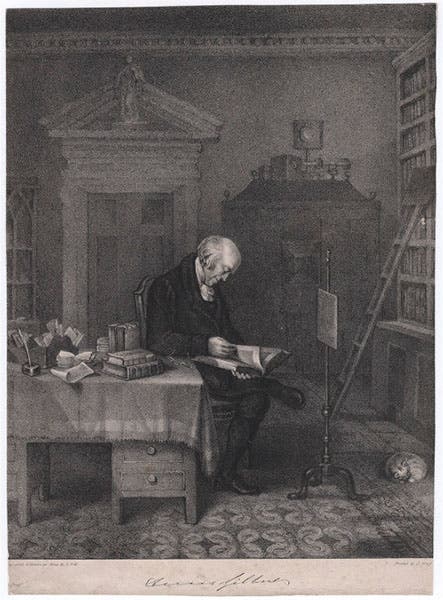

Davies Gilbert, an English political figure and promoter of science, was born Mar. 6, 1767, in Penzance, Cornwall. Gilbert was born Davies Giddy, but he took the surname of his wife, Mary Ann Gilbert, so that he could inherit the Gilbert family estate, which was considerable. Gilbert was the kind of scientist who is often overlooked in historical studies, because he was not much of a genius, nor did he make original contributions to any field of science. But without the Gilberts of the world – identifying talent, pulling strings, persuading sponsors – nothing much happens in the field or laboratory. For example, Gilbert met a young lad in Penzance, recognized his cleverness and intelligence, invited him to his house, introduced him to several local figures who taught the boy chemistry, and before long Gilbert recommended the lad to Thomas Beddoes of Bristol, who was then setting up his Pneumatic Institution and looking for a young chemist. The young man was Humphry Davy, and he would go on to become one of the most brilliant chemists of the early 19th century. Without Gilbert, he might have been thatching roofs in Cornwall.

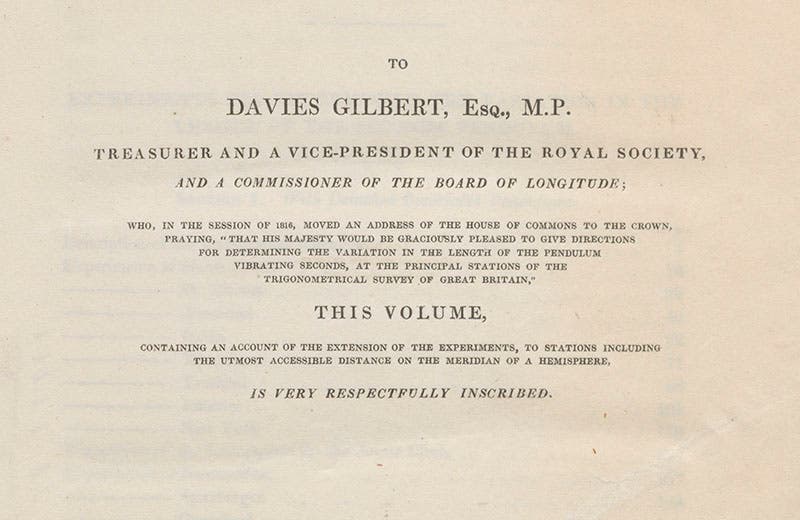

When Richard Trevithick was attempting to build the first steam locomotive in 1801, also in Cornwall, it was Gilbert, unasked, who provided the financial backing that allowed Trevithick to succeed. Gilbert became a member of Parliament, the Royal Society of London, and the Board of Longitude, so he had considerable clout, and in 1816, he made a plea in the House of Commons that the government support a trigonometrical survey of Great Britain, using the variation in the length of a seconds pendulum to determine the gravitational pull at each designated location and thus the exact shape of the earth. The government was persuaded, and the principal scientist chosen for the task was Edward Sabine, later to become famous for his studies of magnetic variation. When Sabine published his pendulum results as An Account of Experiments to Determine the Figure of the Earth in 1825, he dedicated the book to Gilbert, because without Gilbert, there would have been no pendulum survey. (We have a rich association copy of Sabine’s book in the History of Science Collection; it has a presentation inscription to the astronomer Francis Baily, and later came into the possession of Henry Augustus Rowland, who also signed it).

As a last example of Gilbert’s importance, we turn to the Earl of Bridgewater, who left £8000 to the Royal Society to underwrite a series of scientific treatises "on the Power, Wisdom and Goodness of God, as manifested in the Creation", with no further directions. It was Gilbert, serving as President of the Royal Society from 1827-30, who stepped in, decided to fund 8 treatises at £1000 each, and personally selected the 8 authors, thus decisively ending all the squabbling over money that had begun immediately upon the reading of the Earl's will. We have all 8 of the famous Bridgewater Treatises in our Library, and without Gilbert's supervision, it is hard to know whether any of them would have been published. When we wrote a post on one of the authors, Thomas Chalmers, we used the occasion to photograph our complete set, which you can see as the first image here.

In 2004, a collection of Davies Gilbert letters and manuscripts came up for auction at Bonhams in London. It included letters to Davy, Lord Rosse, James Joule, Sir James South, and dozens of other notable contemporary scientists, indicating that Gilbert played a key role in the day-to-day operations of early 19th-century British science. Some knowledgeable collector ponied up £9000 and walked away with a treasure, a healthy slice of pre-Victorian scientific life.

If you have read many of these posts, you might recall our referring, from time to time, to an engraving executed in 1862 that purports to show 51 of England’s distinguished men of science as of the year 1807-08 (see, for example, our profile of Edward Charles Howard. Davies Gilbert was included in that engraving, as one of the 51). We show you here a detail of the left third of the engraving. Gilbert is the 12th figure from the left, about in the center of our detail, just slightly behind and to the left of Sir Joseph Banks, who sports the sash and star of the Order of the Garter. You can see the complete engraving here, with live links to help identify each of the persons included. Humphry Davy is no. 22 (not in our detail), and Richard Trevithick is at the very right of the complete engraving, at no. 51.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.