Scientist of the Day - Donald McKay

Donald McKay, a Canadian/American shipbuilder, died Sep. 20, 1880, at age 70. McKay was born in Nova Scotia and moved to New York City when he was 16 years old to become a shipbuilder’s apprentice. In those days, the New York shipyards were turning out the fastest large sailing ships in the world, intended for trade to China and Australia, where speed was of the essence. The clipper ship, with sleek lines and a massive amount of canvas sail, was the ultimate sailing machine, and the first great American architect of clipper ships was John Willis Griffiths, in the 1840s. Some of his clippers set speed records that were never broken. We have written a post on Griffiths. The only other American architect with a comparable record was Nathaniel Palmer, about whom we have also written a post.

Ship design in the 1840s and 1850s was pretty much a seat-of-the pants affair. You built a ship, observed how it moved through the water and into the wind, and then in your next ship, you changed a few things, such as the shape of the bow, or where you situated the widest part of the hull, or the amount of "dead rise," the upslope of the hull as you moved forward. There were a few individuals who investigated ship hydrodynamics experimentally, and one of them, Mark Beaufoy, wrote a book on the subject, Nautical and Hydraulic Experiments, published posthumously in 1834 (we have two copies in our collections). Scholars think that Griffiths learned a few things from Beaufoy's book.

Whether McKay read books on naval architecture, we do not know. We do know that he was a craftsman, so that his ships were well-built and looked at home on the water. He moved to Boston and set up his own shipyard, and his first customers bought his ships, which were ordinary schooners and packets, because they were sound and pleasing and came in on budget, and they performed well on the high seas. But in 1849, gold was discovered in California, and suddenly a lot of people wanted to get there as fast as possible, and a lot of other people wanted to ship goods there just as fast to sell at a profit. The quickest route was around the Horn by clipper ship, although it required a different kind of ship, one built both for speed and for tonnage (tea clippers needed only speed).

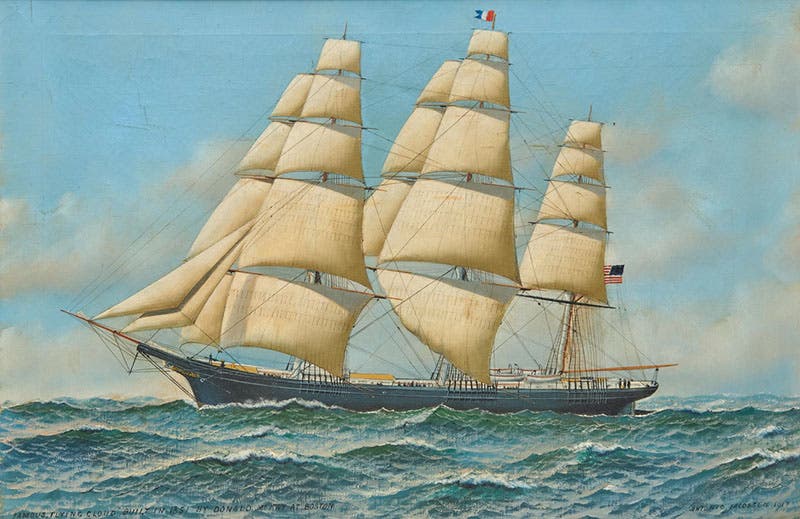

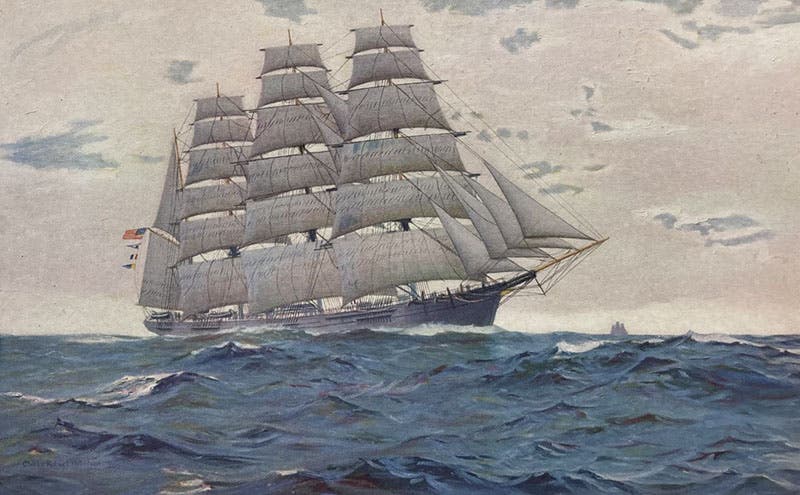

So that is what McKay started building, ships that could weather the storms around the Horn and still make good time. In 1851, he launched his first large clipper ship, the Stag Hound, which is described as an "extreme clipper," meaning it was larger, and sleeker (had a larger length-to-width ratio) and had more sail than the first clipper ships. In that same year, McKay's yard in Boston launched the Flying Cloud and the Flying Fish and two others. The Flying Cloud (first image) made a passage to San Francisco in 89 days, a month quicker than many other ships, and did so twice. In 1852, the Sovereign of the Seas was launched, which had a displacement of 2400 tons, large for a clipper, at least in 1852 (the Stag Hound had a displacement of 1500 tons) and was bought as she came down the slips by a shipping firm that was blown away by her look (third image).

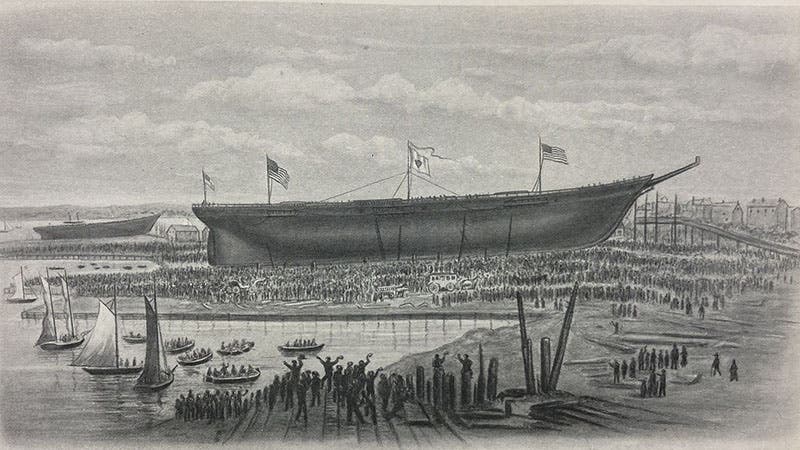

In 1853, McKay launched the Great Republic, which at 4555 tons was the largest clipper ship ever built (fourth image). Its launch was a big event in Boston (fifth image). Unfortunately, as she was taking on cargo for her first voyage, she caught fire and burned down below deck level. She was later refitted by another firm and had a serviceable life in her rebuilt state.

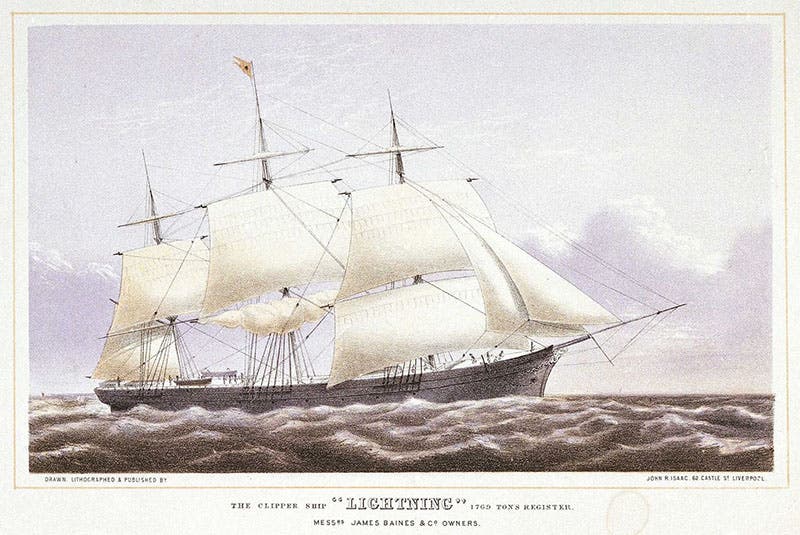

The Lightning was launched in 1854, and it also burned while taking on wool in Australia, but not until 1869, and not until after she set a speed record by sailing 436 nautical miles in 24 hours, a record that stood until well into this century, and may well still stand (sixth image). However, it should be noted that many of McKay's ships sailed 420 or more miles in a 24-hour span on multiple occasions.

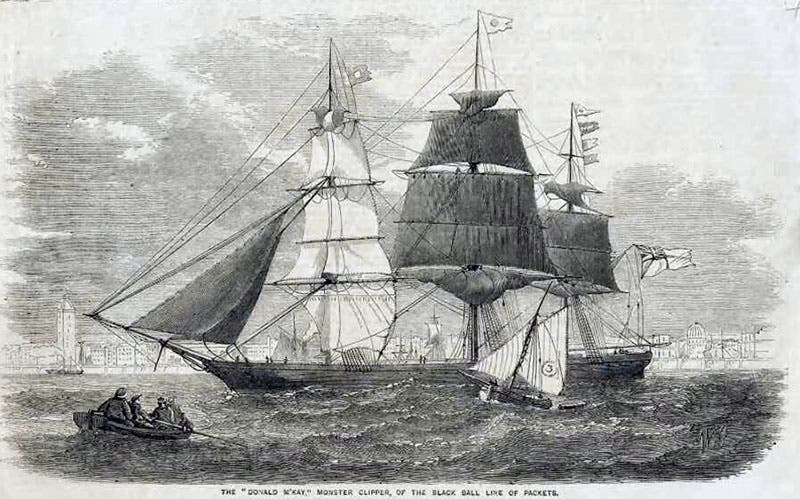

Mackay's last extreme clipper ship was his namesake, the Donald McKay, almost 2600 tons, launched in 1855. It plied the seas for 33 years. Thereafter, the demand for new clipper ships dried up (although the discovery of gold in Australia in 1851 kept things going for a while), but after 1855, the market was gone, and McKay made smaller mid-size sailing ships for the rest of his career. It is a close call with Griffiths and Palmer as to who was American’s greatest shipbuilder, but if you restrict it to extreme clipper ships, McKay surely wins the title.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.