Scientist of the Day - E.O. Wildman Whitehouse

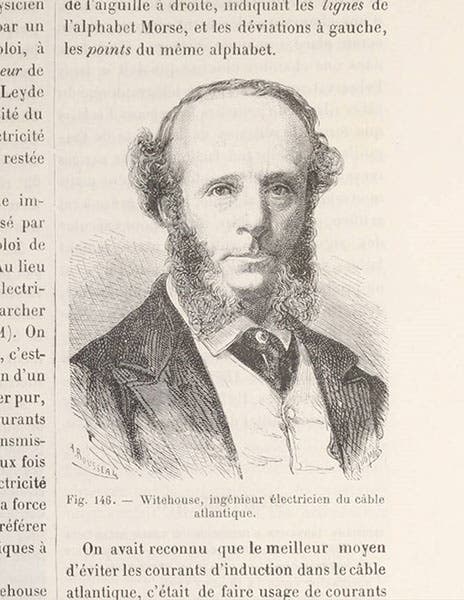

Edward Orange Wildman Whitehouse, an English telegraph electrician and surgeon, was born Oct. 1, 1816. Although Wildman, as he called himself, was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons and had a respectable medical practice, he occupied himself, after 1850, mostly with his hobby, which was designing telegraphic apparatus for undersea cables, which were appearing in increasing numbers in that decade. Whitehouse impressed Cyrus Field, the American financier who was organizing a submarine cable assault on the Atlantic Ocean in 1857-58, and C.F. Varley, who led successful efforts to lay cable across the English Channel, and they hired Whitehouse to be the chief electrician for the Atlantic cable effort. William Thomson, later to become Lord Kelvin but in 1857 merely a Scottish physicist of great promise, was also brought into the project, although Thomson and Whitehouse seldom agreed on what, electrically, should be done.

Laying the cable was a formidable problem, but so was sending and detecting a signal through a cable that long. Thomson invented a very sensitive instrument called a “mirror galvanometer,” which could amplify the faintest signal into a visible motion.

Whitehouse invented his own instrument, a magneto-electrometer, which he preferred. The problem was that it was not clear what exactly Whithouse’s instrument was measuring, as he chose not to use “quantity”, “intensity”, and “resistance” (amperage, voltage, and resistance, the three variables in Ohm’s law), which all the professional electricians like Thomson were adopting.

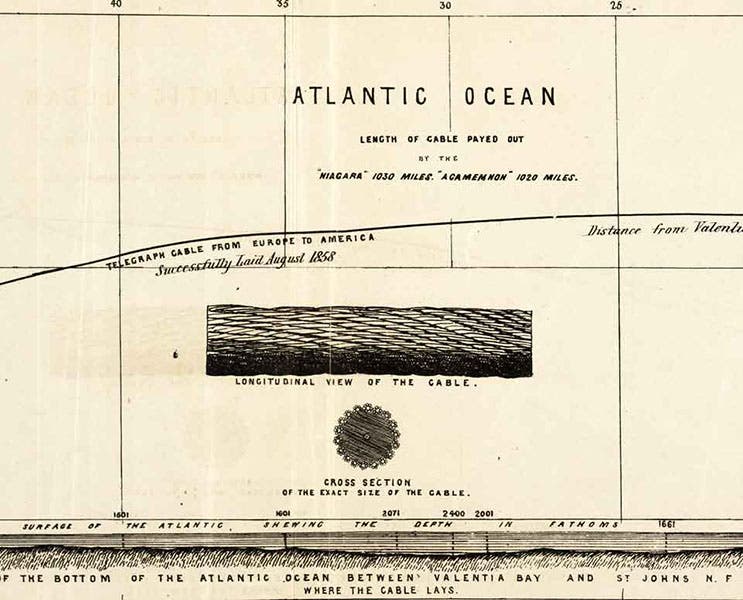

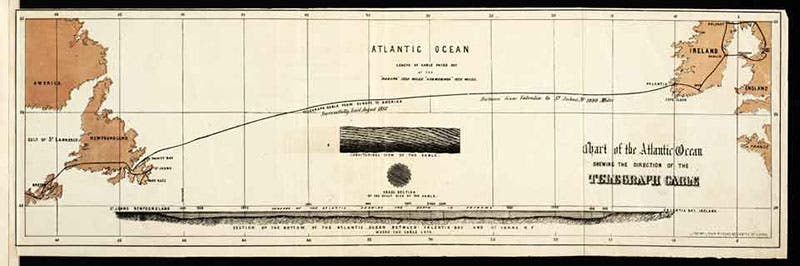

Map of the route for the Atlantic cable-laying attempts of 1857-58, fold-out colored lithograph in Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore: A Series of Sketches Drawn on the Spot by John R. Isaac, and Printed by Him in Tinted Lithography with Explanatory Details, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

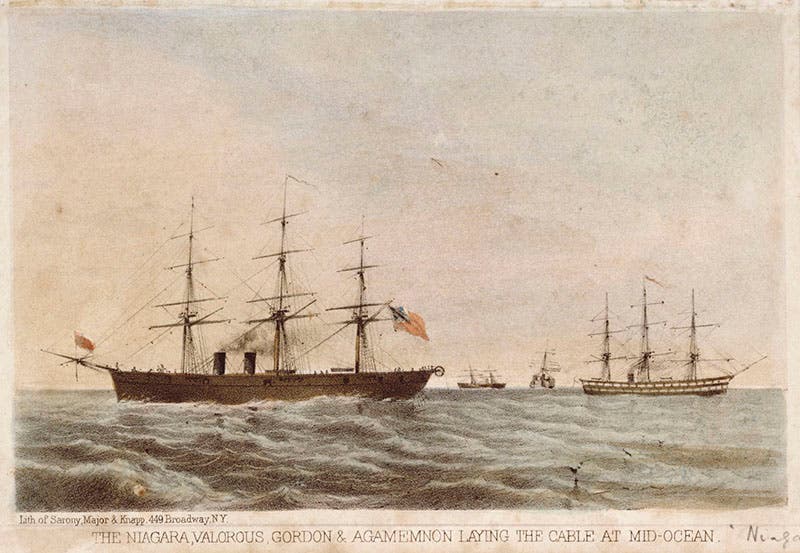

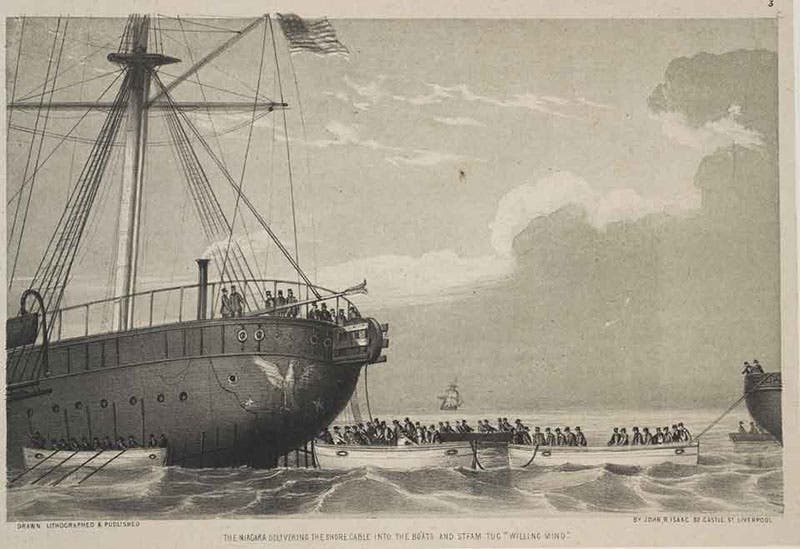

The cable was made by the Glass-Elliot Company, with the insulating layer added by the Gutta Percha Company, and the 2500 miles of cable was loaded onto two ships, the USS Niagara and the HMS Agamemnon. The 1857 venture was short lived, as the cable repeatedly broke and they gave up for the season after three tries. But they still had enough cable on board to stretch from Ireland to Newfoundland, so in the summer of 1858, they started in the middle of the Atlantic and went both ways. The first venture failed, but they had time to start over, in July. Interestingly, Whitehouse, claiming illness, was not on board either ship, although the Chief Electrician was responsible for testing the cable as it was laid. His place as Chief Electrician was taken by Charles Tilston Bright; Thomson seems to have done most of the on-board testing. In fact, Thomson was on board for all 5 cable-laying attempts of 1857-58 (and for the two successful ones of 1865-66). Whitehouse set up at Valentia in Ireland, the eastern terminus for the cable, ready to receive signals if the cable-laying was successful. The cable-laying was competed on Aug. 5, and by gosh, the thing worked. Signals came to Valentia from Newfoundland and Whitehouse did his best to decipher them. He claimed that he used his own instrument as a receiver, but it later came out that his instrument failed to do the job, and he secretly used Thomson’s galvanometer to detect signals. Whitehouse was fired from his job, allegedly for insubordination..

Everyone celebrated the success of the 1858 cable; there were wild parties in New York City; the Queen sent a telegram to President Buchanan on Aug. 16, and he sent one back (the Queen's message, a short paragraph, took 16 hours to transmit, since they were using Whithouse’s instrument in Labrador; Buchanan's was received much more quickly on the British end, using the mirror galvanometer). And then suddenly, on Sep. 2, the cable failed, and it would never be restored. Accusations flew in every direction, and soon the blame settled on Whitehouse. Whitehouse, it turned out, had used a 5-foot induction coil to send signals from Ireland, which subjected the cable to perhaps 2000 volts, and this caused the failure. Or so concluded a board of inquiry in 1861.

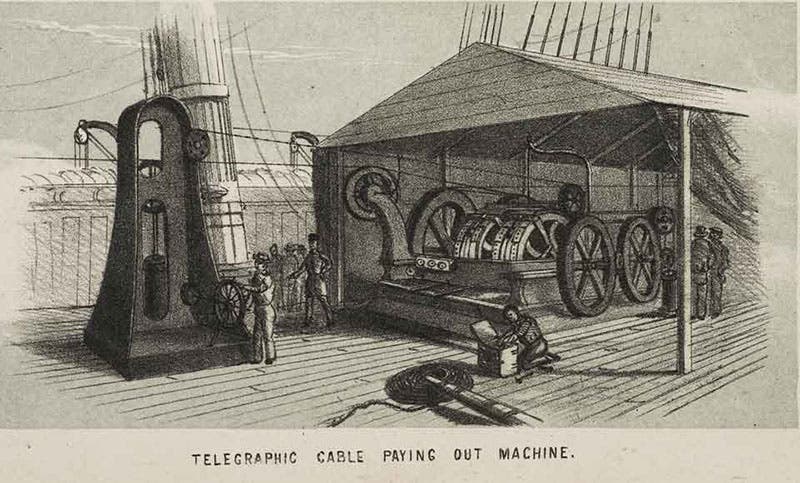

This is the standard story of the Atlantic cable of 1858 still being told – indeed, I just told it. Recently, Whitehouse has attracted defenders. Some wonder why, if Whitehouse were so incompetent, he and Thomson maintained a healthy and even friendly professional relationship well through the 1860s. Others point out that the cable was doomed from the start, because it was shoddily made, improperly stored, both on shore and on ship, excessively strained in the paying-out process, and destined to short out at the first opportunity. These critics argue that Whitehouse was made the scapegoat to protect the cable manufacturers and Field's Atlantic Telegraph Company from well-deserved criticism.

We don't know. All we do know is that when the cables of 1865 and 1866 were laid – both ultimately successful – Whitehouse was nowhere to be seen, and Thomson, with his mirror galvanometer, oversaw all things electrical. Of course, the cable was thicker and better made, the cable storage on board ship was safer, the paying-out apparatus was improved, so perhaps it would have been successful with Whitehouse in charge. Myself, I don’t think so, even if the 1861 charges of misfeasance went too far. Thomson was really good at what, for him, was a profession, not a sideline, and he was probably essential for the success of the 1865-66 cables.

At the Library, we have a fine collection of material relating to both Atlantic cable projects, which we have drawn on for some of our images. The portrait of Whitehouse is from Louis Figuier’s Les merveilles de la Science, 1867, which we have often utilized for portraits in these anniversaries.

The most thorough and even-handed discussion of Whitehouse and his role in the Atlantic cable failure of 1858 is in a book by Bruce J. Hunt, Imperial Science: Cable Telegraphy and Electrical Physics in the Victorian British Empire (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021), where Whitehouse is the subject of the second and third chapters.

You can read more about the Atlantic cable ventures of the 1850s and 1860s in our posts on Cyrus Field, George Elliot, Matthew Fontaine Maury, and Samuel F.B. Morse. Our post on William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) barely mentions his role in the Atlantic cable projects; we need to write a second post and discuss his mirror galvanometer.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.