Scientist of the Day - Edward Bagnall Poulton

Edward Bagnall Poulton, an English entomologist and evolutionary zoologist, was born Jan. 27, 1856. Poulton eventually (1893) became the Hope Professor of Zoology at Oxford, a chair founded in 1860 by Frederick William Hope and first occupied by John Obadiah Westwood. Poulton was the second Hope professor, and he held the chair for fifty years, until his death in 1943.

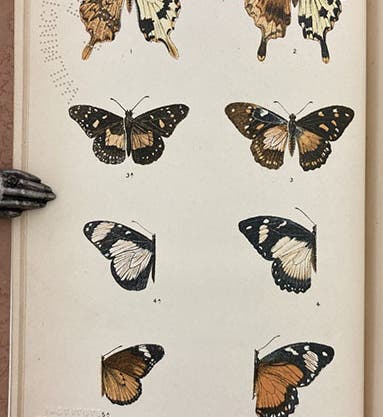

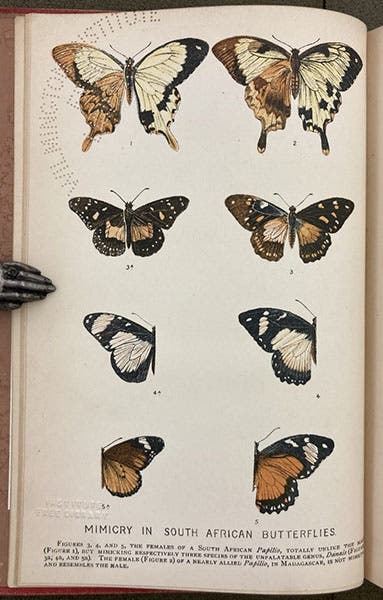

There were many evolutionary biologists in the 1890s, but not so many who accepted Charles Darwin's principle of natural selection as the primary evolutionary mechanism. Poulton was one of those few. He published a book in 1890, The Colours of Animals, which is primarily concerned with mimicry, and he argued that every known instance of mimicry (such as edible butterflies that resemble unrelated and foul-tasting butterflies; first image) was explainable by the accumulation of random variations acted on by natural selection. He also wrote a more general work, Charles Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection (1896 – we have the New York edition of that same year), in which he tried to explain how natural selection worked and why it provided a more satisfactory explanation than other mechanisms, such as Lamarckian inheritance of acquired variations.

Poulton seems to have been an eminent entomologist, and worthy of honoring on those merits, but to me, he is memorable because of a story he related about Darwin, a story we would never have known if he had not passed it on, even though he was not a participant in the events of the story. 1909 was a big year for Darwin celebrations (as was 2009 in our own century), because Feb. 12, 1909, was the 100th anniversary of Darwin's birth, and Nov. 24, 1909 was the 50th anniversary of the publication of the Origin of Species. Poulton took an active role in organizing celebrations in England, and he edited a celebratory book, Charles Darwin and the Origin of Species; Addresses, etc., in America and England in the Year of the Two Anniversaries (1909), which was deliberately published on the same day, Nov. 24, as the Origin of Species. Near the end of the book, Poulton included some unpublished correspondence between Charles Darwin and Roland Trimen, an English zoologist working in South Africa. By way of introduction to the letters, Poulton passed on this story, told to him by Trimen.

The scene is the Insect Room of the Zoological Department of the British Museum, probably in early 1860, as Trimen recalled (and Poulton related): "One day I was at work in the next compartment to that in which Adam White sat, and heard someone come in and a cheery, mellow voice say, ‘Good-morning, Mr. White; – I’m afraid you won't speak to me any more!’ While I was conjecturing who the visitor could be, I was electrified by hearing White reply, in the most solemn and earnest way, ‘ Ah, Sir! if ye had only stopped with the Voyage of the Beagle!’ There was a real lament in his voice, pathetic to any one who knew how to this kindly Scot, in his rigid orthodoxy and limited scientific view, the epoch-making Origin, then just published, was more than a stumbling-block – it was a grievous and painful lapse into error of the most pernicious kind. Mr. Darwin came almost directly into the compartment where I was working, and White was most warmly thanked by him for pointing out the insects he wished to see. Though I was longing for White to introduce me, I knew perfectly well that he would not do so; and after Mr. Darwin's departure, White gave me many warnings against being lured into acceptance of the dangerous doctrines so seductively set forth by this most eminent but mistaken naturalist." The Trimen-Poulton story is a vivid reminder of how appalled many naturalists were by Darwin’s Origin of Species. It is a story best told aloud, and if you can adopt a rich Scottish brogue when lamenting “Ah, Sir! If ye had only stopped with the Voyage of the Beagle!”, it is even better.

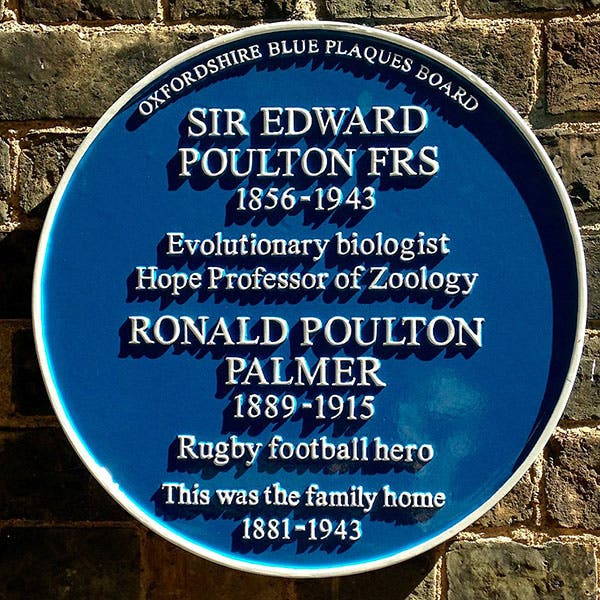

Poulton’s family life was less happy than his professional career. He had five children, and he outlived four of them. His son Ronald was more famous than father Edward, being an international rugby player of uncommon skill, who once scored five tries against Cambridge. He was killed in Flanders in 1915. Gerald and Ronald, unusually, share a blue plaque at their former home in Oxford (fifth image).

There are four photographs of Poulton in the National Portrait Gallery in London but all were taken in 1935, long after the events of this post. We prefer a detail of a group photo of members of the Entomological Society of London, taken in 1904, where Poulton is seated at front center (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.