Scientist of the Day - Edward Belcher

Edward Belcher, an officer in the Royal Navy, died Mar. 18, 1877, at the age of 78. You may have heard of the Peter Principle, applied to competent people who are eventually promoted beyond their ability to a level of incompetence. There ought to be a Belcher Principle, applied to people who are incompetent from the beginning and who are continually promoted as a way of solving the incompetence problem. By all accounts, Belcher was arrogant, generally uninformed on any matter you might wish to discuss, hated by everyone in his various commands, and, yes, incompetent.

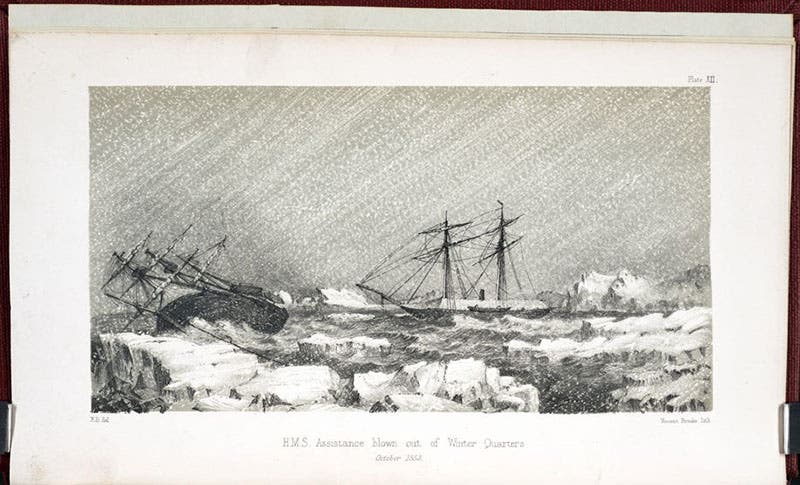

Belcher was commander of several expeditions in the 1830s and '40s, where his knack for alienating his men first emerged. Thus it was a surprise when, in 1852, he was chosen to lead the Arctic Squadron, a fleet of five ships sent into the Arctic archipelago to look for the lost Franklin expedition, which had sailed in 1845 and disappeared. The Arctic Squadron was a complete failure, if finding a trace of Franklin is the measure of success, and after two winters, Belcher ordered his commanders, over their vigorous objections, to abandon their ships, which were frozen in the ice, and return to England on the supply ship. Belcher was court-martialed for leaving four ships behind, and acquitted, but he was made to look fairly silly when one of the abandoned ships, the Resolute, freed itself the next year and floated out into Baffin Bay, where it was recovered by an American whaler. Belcher was never given another command, but he was promoted eventually to Admiral, to go with his earlier knighthood.

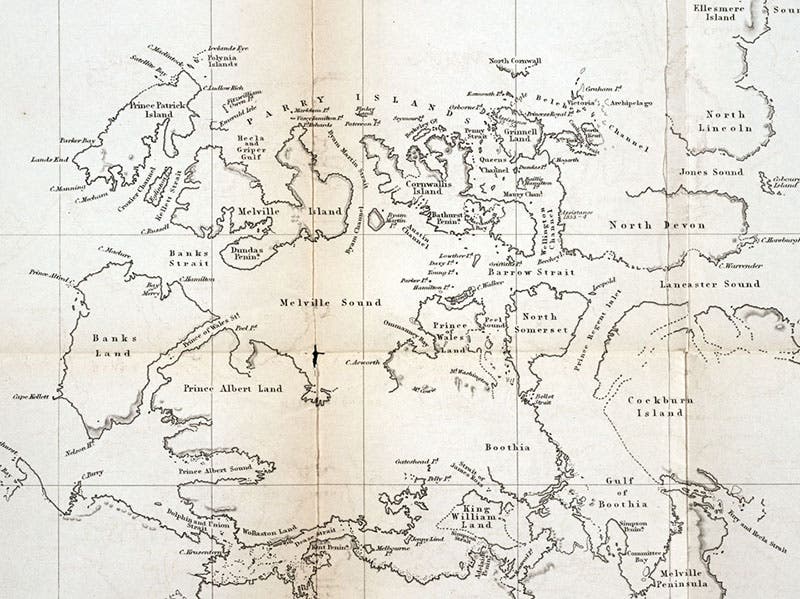

The map of the expedition does not include routes and anchorages, but it does show what was known about the Arctic archipelago in 1852; we include here a detail of the published map (fourth image, just below). The ships entered through Lancaster Sound at the right, which connects to Baffin Bay. Their base of operations was Barrow Strait; they explored up Wellington Channel and Austin Channel and into Melville Sound. They did not go south, which is where Franklin’s ships had frozen in, near King William Land. But those ships had long since sunk anyway.

Interestingly, Belcher’s four primary officers on the Arctic expedition – Henry Kellett, Sherard Osborn, Francis McClintock, W.J.S. Pullen – were all extremely competent Arctic explorers, and each made important contributions to polar science during the three-year voyage, and on later expeditions. Many of the crew went out on extended sledge expeditions during the long winters – one way of escaping the presence of Belcher – and one of these expeditions discovered HMS Investigator, which had entered the archipelago from the west in 1851 and was frozen in at Mercy Bay on Banks Land. The crew was rescued. McClintock, captain of the Intrepid, would later, on a privately financed expedition in 1859, solve the mystery of the disappearance of Franklin and his crew.

Belcher published an account of his expedition in 1855, which he inexplicably titled The Last of the Arctic Voyages, as if to say, well if I couldn’t do it, no one can. We displayed Belcher’s narrative of the 1852-54 expedition in our Ice exhibition in 2009, and all of our images today, except for the portrait, were taken from Belcher’s narrative. I am happy to report that our copy of Belcher’s account is in poor shape and falling apart; since the plates are in good condition, we have never been tempted to replace it.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.