Scientist of the Day - Edward Donovan

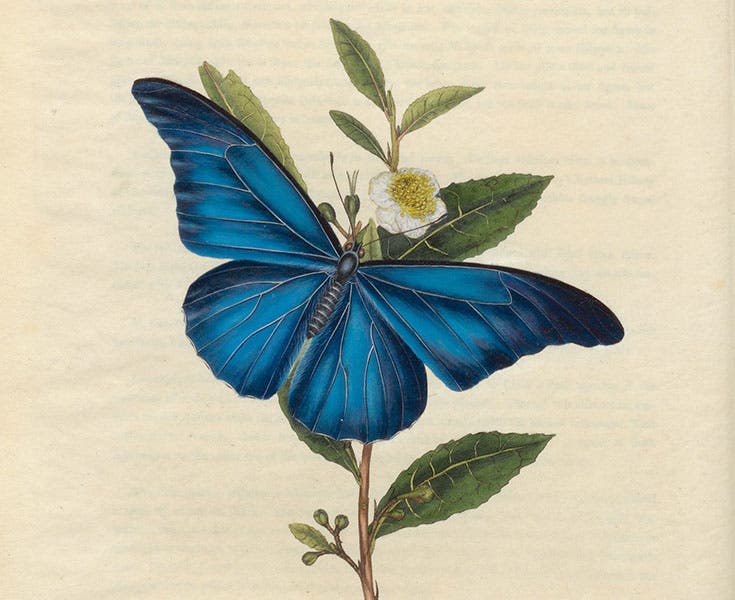

Edward Donovan, an Irish/English naturalist and illustrator, was born Feb. 1, 1768. Donovan was a prolific writer and self-publisher of a variety of books on the natural world, mostly about insects, which he collected avidly. He was strictly a stay-at-home naturalist, buying his specimens from field collectors or at auction in London. Little is known about his background, but his books generated enough respect that he was welcomed into the field by the likes of Joseph Banks and Dru Drury, and was made a fellow of the Linnean Society of London. We wrote a profile on Donovan five years ago on this day, where we displayed some of the hand-colored engravings in his Epitome of the Natural History of the Insects of India (1800), and our point was simple: to show that Donovan published some of the most beautiful natural history illustrations ever put into print, made glorious mostly by the meticulous hand-painting of the engraved plates.

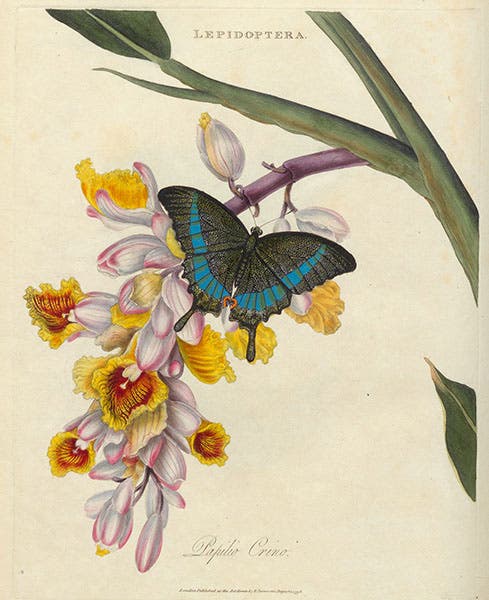

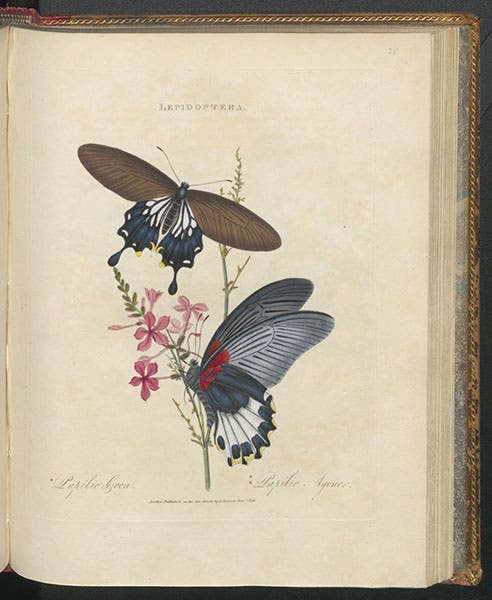

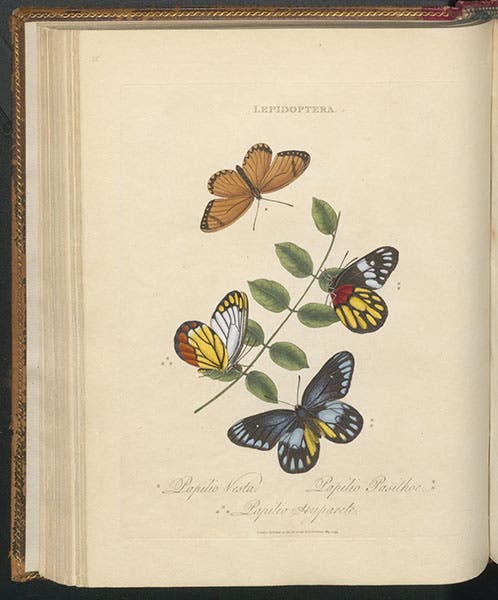

Today we focus on another Donovan book in our collection, Epitome of the Natural History of the Insects of China (1798), written two years before the compilation on India. I think the illustrations in the book on India are my favorite Donovan plates, because of the rich hand-coloring, but the book on China comes in a close second. Donovan had never been to China – he had hardly been out of London – so all of the specimens described were either ones he had purchased, or ones he had seen in the collections of others such as Drury and Banks. For scientific information, he relied on the first systematic Linnean entomologist, Johann Christian Fabricius. Unfortunately, the insect nomenclature of Linnaeus and Fabricius was very simplistic – Linnaeus put all butterflies in the genus Papilio, and all moths in the genus Phalaena. So every one of Donovan’s Chinese butterflies starts with Papilio, which we now use only for swallowtails. Since I don't know much about the insects of China, I have used Donovan’s scientific names and have not attempted to find the correct modern names for Donovan's species. And the insects I chose to display here are the most attractive ones, which means they are almost all butterflies, and hence all Papilio. If, like J.B.S. Haldane, you are partial to beetles, you will find beetles in the Epitome of the Insects of China, but not here, for such images are small and do not show up well in a forum like this.

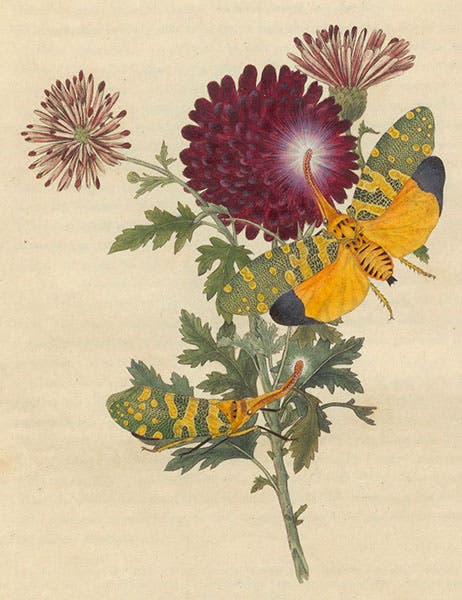

One of Donovan's insects is worthy of further comment, the first in his book, although the last one here (seventh image). It shows two specimens of what he calls Fulgora candelaria, a lantern fly, which Maria Merian had described (says Donovan) as emitting light from its long snout. Donovan has a long discussion about Merian’s observation, and cites critics who adamantly denied Merian’s assertion. But in Donovans’s engraving, the two Fulgoras do indeed have their own little flashlights.

One of the nicer features of Donovan's insect books is that he took care to draw accurately, and then to identify in the text, the plant specimens on which his insects were displayed. The plants were usually well-chosen to provide color balance to the insects, especially the butterflies. Since he took care to identify his plant mounts, we have done so as well in our captions.

Donovan's books – and there were many more than the four we have in our collections – seem to have sold well, so I am not sure why he ended up in such financial distress. He opened a museum in 1807, the London Museum and Institute of Natural History, where he had thousands of specimens on display (and which you could see for a shilling), but the museum closed in 1817, and the next year, his entire collection was sold at auction. By the time he died in 1837, he was as poor as a church mouse, and he left his family only memories and a sizeable debt. His slide into ruin was eerily similar to that of a contemporary naturalist, illustrator, and book publisher, John Robert Thornton, whose Temple of Flora (1807) is perhaps the finest botanical folio ever published, but who also went broke, and died a pauper in the very same year as Donovan.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.