Scientist of the Day - Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus

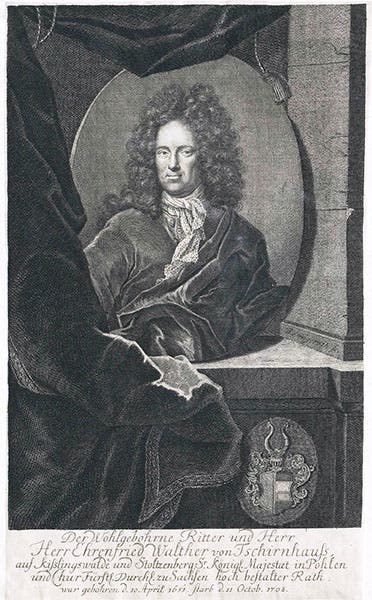

Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, a German mathematician and chemist, was born Apr. 10, 1651. Tschirnhaus was the first person in the West to discover the secret to making true (hard-paste) porcelain. The Chinese and Japanese had been making porcelain for centuries, but no Western potter could duplicate the look and feel of porcelain, a ceramic that is white, translucent, impermeable to moisture, and rings like a bell when struck. The only thing close to it in the West, before Tschirnhaus, was faience or majolica, which is stoneware with a white, opaque tin glaze that at first glance looks like porcelain, but which is porous and does not ring. Tschirnhaus found that one needed three key ingredients to make true porcelain: kaolin, an infusible white clay; a fusible mixture of feldspar and quartz (silica) that was called petunse; plus a kiln capable of firing to a high temperature of 1320° C, or 2400° F), about 75° C higher than that needed for most earthenware. At that temperature, the silica melts to glass and the kaolin does not, producing a hard, translucent ceramic. Tschirnhaus died in 1708, shortly after making the discovery, and his assistant Johann Böttger claimed the credit for himself, but most scholars now give the nod to Tschirnhaus. The Meissen porcelain factory was established in 1710 to make porcelain using Tschirnhaus's secret recipe and technique, and it is still in business today. The Nelson-Atkins Museum here in Kansas City has several specimens of early Meissen porcelain; we link to a decorated plate from around 1730), and show here (first image) a cream pot made about 1720 that may or may not be in the Nelson-Atkins collection, but which was exhibited there in 2011.

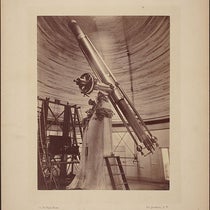

The portrait of Tschirnhaus that we include here is an engraving made after his death, not signed but attributed to Martin Bernigeroth (second image). There is a memorial plaque in Görlitz, the town in Saxony where Tschirnhaus went to school. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.