Scientist of the Day - Eli Whitney

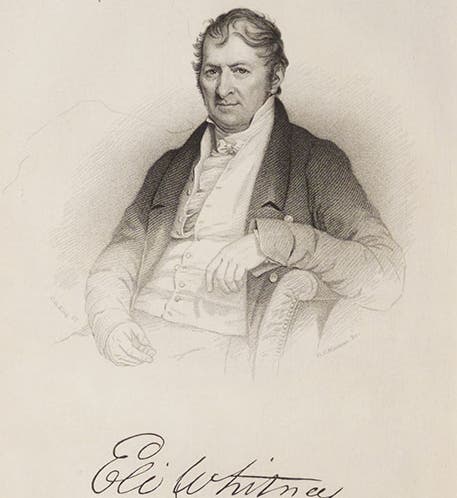

Eli Whitney, an American manufacturer and inventor, was born Dec. 8, 1765, in Massachusetts. The son of a farmer, he graduated from Yale College in 1792. He is now known for two achievements: inventing the cotton gin, and developing the system of using interchangeable parts in the manufacture of guns. He deserves credit for the first of these achievements, but the second claim is a myth, unsubstantiated by any evidence whatsoever.

The cotton gin came first. Whitney was visiting Georgia in 1793 when he learned of the difficulty of separating short upland cotton from its seeds. It took an entire day for a slave laborer to produce just one pound of fiber, making the crop uneconomical. Whitney's simple invention consisted of a crank that turned a cylinder with hooks that pulled the cotton lint through slots too small for the seeds, and it worked amazingly well, even in its first incarnation, producing over 50 times as much cotton as a human working by hand. There is a Whitney cotton gin (apparently a later model, since it has saw-tooth blades rather than hooks) at the Eli Whitney Museum in Hamden, Conn., just north of Yale (second image). Whitney patented his invention, but patent law was in its infancy, with many loopholes, and he was unable to enforce his patent as competitors began to turn out copies. Whitney lost all the lawsuits he brought and was on the verge of bankruptcy by 1798.

Fortunately for Whitney, the U.S. government, fearing war with France, put out a call for firearms, and Whitney was able to finagle a contract that paid him $5000 up front, thereby saving him from financial ruin, and this in spite of the fact that he had never made a gun and had no factory to supply the 10,000 rifles he had contracted to supply in the next 30 months. He eventually did fulfill the contract, building a factory along the Mill River in Connecticut, but he was nine years late in doing so.

It was while building his firearms factory that Whitney supposedly developed a system of using interchangeable parts, which later became a mainstay of what is often called the "American System" of manufacturing. Whitney claimed that was the case in the 1820s, and his first biographer, Denison Olmsted, an astronomy professor at Yale, repeated that assertion in his biography of Whitney, published first in the American Journal of Science in 1832, and then as a book in 1846 – we have both versions in our collections. The belief that Whitney invented interchangeable parts became part of conventional wisdom, repeated even by reputable historians, until 1960, when one of the premier American historians of technology, Robert S. Woodbury, decided to examine the evidence. In a classic article published in Technology and Culture, he found that the idea of interchangeable parts originated in Europe well before Whitney, that Whitney himself did not use interchangeable parts in his Mill River factory, and that the best claimant for being the first American to use interchangeable parts in a production factory was John H. Hall, who built the armory at Harper’s Ferry and was assembling firearms using interchangeable parts by 1819. The claim for Hall has substantial documentary evidence to support it, unlike that for Whitney, which has none.

Still, the cotton gin was an ingenious invention, and Whitney deserves credit for that, even if, by making upland cotton a profitable crop, it inadvertently helped perpetuate plantation slavery in the American South. In addition to a cotton gin, the Eli Whitney Museum has many other Whitney-related items. I have not been to the Museum, even though it is not far from where I grew up in Farmington, but it does seem worth a visit. On the museum website, they show a painting, owned by Yale Art Gallery, by William Giles Munson, that depicts the firearms factory built by Whitney at Mill River, where Whitney produced rifles with parts that were demonstrably not interchangeable (third image).

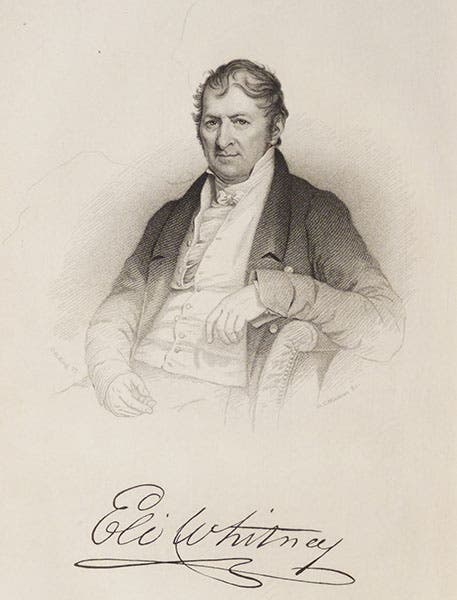

Our copy of Denison Olmsted’s Memoir of Whitney was presented to one of the engineering society libraries in New York in 1893 by Eli Whitney III, who went by the name Eli Whitney, Jr. (as his father, the real Eli Whitney, Jr., went by Eli Whitney). It came to us when we acquired the Engineering Societies Libraries in 1995 (fourth image)

Olmsted’s Memoir may be unreliable as a biography, but it does display a frontispiece portrait of Whitney, which we used as our first image. It also has a lithograph of Whitney's tomb at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven (fifth image), which is useful, since the inscription is now obscured by a protective cast iron fence, as you can see if you visit Whitney’s entry at findagrave.com. And if you read the biographical entry at this website, you will see that the Whitney legend lives on in the public realm, despite the detective work of Robert S. Woodbury and others.

Thanks to Benjamin Gross, our resident historian of technology, for welcome advice on this post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Front paper cover of Memoir of Eli Whitney Esq., by Denison Olmsted, 1846, with presentation inscription by Eli Whitney [III] (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/ad24d9bf-d3ea-4ebe-a09c-8c2f2023d344/whitney4.jpg?w=368&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)