Scientist of the Day - Emily Warren Roebling

Emily Warren Roebling, an American civil engineer by necessity, was born Sep. 23, 1843. Emily was the much younger sister of Gouverneur Kemble Warren, who played a notable role in both Western exploration and the Civil War. General Warren's aide-de-camp at Gettysburg was Washington Roebling, a civil engineer during times of peace, and Emily met Washington at a military ball in 1864; the two were married a year later. Washington in turn was the son of John Augustus Roebling, who, immediately after the end of the Civil War, conceived the idea of building a suspension bridge across the East River connecting New York City and Brooklyn. John Augustus managed to convince both sets of city fathers and various financiers that the project was feasible, and the project was ready to go in 1869, when John had his foot crushed between a tug and a pier. During either the accident or the resulting surgery, he contracted tetanus, which led to his protracted and unpleasant death a month later. Fortunately, John had fully involved his son in the construction of a suspension bridge at Cincinnati in the previous years, and in the planning for the East River Bridge, so rather than abandon the project, the Board placed the thirty-two-year-old Washington in charge. Emily and Washington immediately moved to a house in Brooklyn Heights, and Washington went to work.

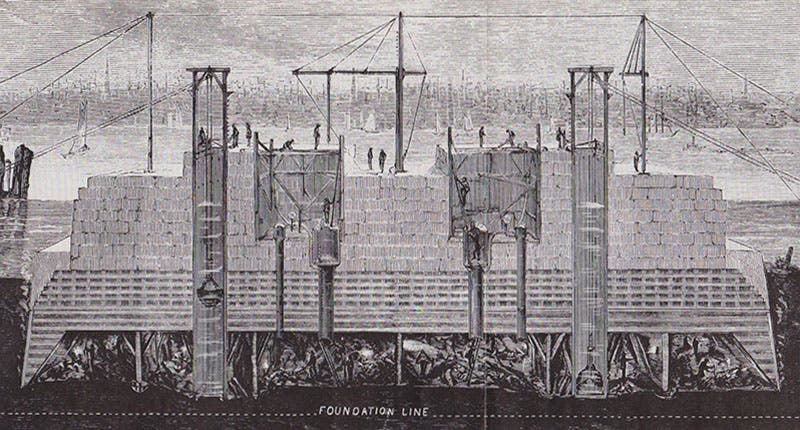

The immediate task was to sink the caissons that would support the 275-foot granite towers on both the Brooklyn and New York City sides of the river (no one used the term “Manhattan” back then). Caissons were brand new in the United States; they were large boxes that were placed open-side-down on the river bottom and then pressurized, so that workers inside could dig out the earth or stone beneath and gradually sink the caisson. As the caisson went down, the bridge tower was built up on top, and gradually rose out of the water. We see here a cutaway of the Brooklyn caisson. James Buchanan Eads was using caissons at this very time to build his bridge over the Mississippi at St. Louis, but no one yet knew about "caisson disease," later to be called "the bends," which began to afflict workers once they were down about 50 feet below water level in the pressurized caissons. One day in 1870, a fire broke out in the ceiling of the Brooklyn-side caisson, the first to be submerged, and Washington spent several long days down in the caisson fighting the fire. When he emerged, he was struck down with the bends. He partially recovered from this first episode, but another crisis in the New York City caisson took him below again in 1872, and this time he did not recover. He barely survived with his life, and he never returned to the construction site. Afflicted with excruciating pain and deteriorating eyesight, he worked entirely from home for 11 more years, and the only Brooklyn Bridge he would ever see was the one viewed from his window in Brooklyn Heights.

At this point, Emily took over. At first, she merely relayed instructions from Washington at home to the assistant engineers at the bridge. But often unable to see well enough to write, Washington would dictate his instructions to Emily, who wrote them down. As time went by, she learned more and more about the engineering problems, and their solutions, and most scholars believe that in the last years, Emily was really in charge. Certainly, when she herself went down to the bridge, everyone treated her like the Chief Engineer, which was Washington's title. It is unfortunate that we don't know more about Emily, for she appears to have been a remarkable and supremely talented woman. In addition to mastering the technical details of the bridge, she was a genius at diplomacy, soothing ruffled feathers and negotiating compromises, and this was sorely needed, as the various boards and councils that oversaw construction were extremely contentious.

Just before the bridge was opened on May 24, 1883, a ceremonial crossing by foot was organized, and Emily was given the privilege of being the first to cross, although she graciously insisted that the assistant engineers join her. After the East River Bridge was completed, and before it came to be called the Brooklyn Bridge, Emily and Washington moved back to Trenton, where the Roebling Wire-Rope factory was located. A portrait survives of Emily wearing the dress in which she met Queen Victoria (third image). The portrait hangs in the Brooklyn Museum, presumably next to the portrait of Washington Roebling, painted in 1899 (fourth image). Emily died in 1903, just before she turned 60. Washington, the stubborn old cuss, lived with his painful afflictions until 1926, dying at the age of 89.

In 1951, the Brooklyn Engineers Club installed a plaque on the bridge, commemorating the work of the Roeblings, and included Emily in the bronze citation (fifth image) . The next-to-last sentence is a little hard to read today, with its reference to “the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman,” but it was 1951, after all, and at least they did put Emily’s name at the top, surmounting those of Washington and John Augustus, which is just where she belonged. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.